Huston Smith and the seekers of Trabuco Canyon

Huston Smith was at Berkeley working on his Ph.D. in 1945 when he stumbled upon the work of Gerald Heard, a British writer and philosopher—a man who would later be called “the grandfather of the New Age movement.”

Smith, who would later write The World’s Religions, a book first published in 1958 and still widely used as a religious studies text, had come to Berkeley from Chicago in 1944 with his wife, Kendra, and their daughter, Karen. He was already an ordained minister in the United Methodist Church and spent his weekends down on the Monterey Peninsula, where he had a part-time job leading Sunday services at a small church with a congregation composed mainly of local cannery workers.

During the week, Smith passed most of his waking hours in the library or in his room at a boarding house just off campus. He was working on his dissertation under the direction of Professor Stephen C. Pepper, whose long tenure in the Department of Philosophy stretched from 1919 to 1958. Every Friday at noon, Smith would put away his books and take a series of buses from downtown Berkeley all the way out to Highway 101, where he would disembark and then hitchhike down to Monterey to spend the weekend with his young family.

One weekday, back in Berkeley, Smith found himself thumbing through the card catalog at Doe Library, looking for books with the word pain in the title. That’s when he discovered an intriguing 1939 work by Gerald Heard called Pain, Sex and Time—A New Outlook on Evolution and the Future of Man. Smith checked the book out, took it back to his boarding house, and stayed up the whole night reading. As he relates in his Foreword to the book’s 2004 edition, “When dawn broke I was living in the new world that has housed me ever since.”

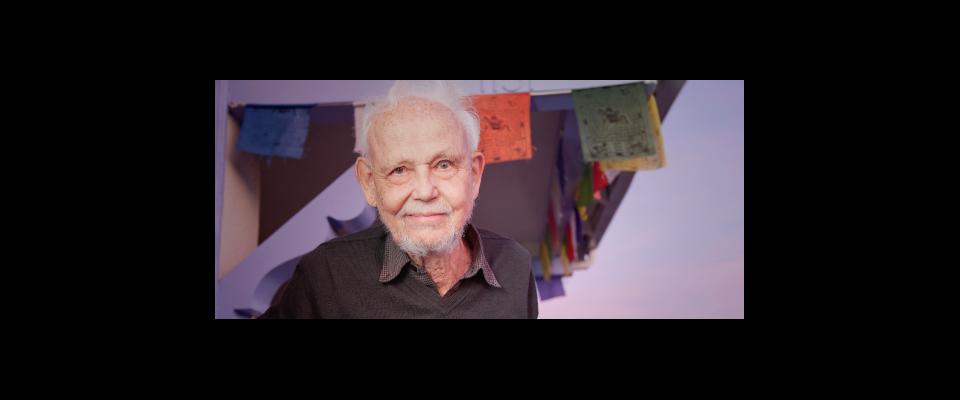

“Overnight,” said Smith, now 91 years old and living in Berkeley, “that book converted me from the scientific worldview to the vaster world of the mystics. I was taken by Heard’s idea that we were on the cusp of an evolutionary advance—that the tide of evolution would allow mankind to merge with God’s infinite consciousness.”

Gerald Heard was a prolific writer and a respected intellectual of his time. He was a philosopher, a social commentator, and a mystic. Heard was still very much on Smith’s mind when he completed his 312-page dissertation (“The Metaphysical Foundations of Contextualistic Philosophy of Religion: An Inquiry into the Relation of Metaphysics to Religious Knowledge”) and got his first teaching job at Denver University.

Smith vowed to read every book Gerald Heard had ever written—no easy task—and then promised himself that he would meet the man. In 1949, Smith completed his first goal and then wrote a letter to Heard in care of his American publisher, Harper & Brothers in New York. Heard replied with a handwritten note: “I’ll be very happy to meet you, but you may have a little difficulty finding me.”

By then, Heard was at a monastery in the Santa Ana Mountains.

California is notorious for its eclectic spirituality, hybrid religions, and endless self-help schemes. Trabuco College of Prayer is a fascinating and mostly forgotten chapter in the state’s religious history. This seminal retreat in the mountains southeast of Los Angeles was the brainchild of Heard, who, along with fellow English pacifist and writer Aldous Huxley, founded the institution as the United States entered World War II. Trabuco College lasted less than a decade, but its influence has resonated for more than 70 years.

Heard and Huxley created a “club for mystics” that profoundly influenced several architects of the new American spirituality. In addition to Smith, there were Bill Wilson, cofounder of Alcoholics Anonymous; and Michael Murphy, who used Trabuco as the model for Esalen Institute at Big Sur, the birthplace of the human potential movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The spiritual legacy of Trabuco also lives on through the growing legions of Americans who now, according to a 2008 Pew Research Center survey on religion, claim no religious affiliation and might identify themselves as “spiritual but not religious.”

Human potential was the guiding principle behind Trabuco College. Heard and Huxley preached that humanity had the potential for a breakthrough in consciousness. Religious mystics were a kind of spiritual scouting party, showing the way forward. In a series of books, lectures, radio broadcasts, and television appearances in the 1940s and 1950s, Heard and Huxley emerged as the leading evangelists of a religious philosophy that combined Buddhist meditation, Hindu philosophy, spiritualized psychology, psychedelic drugs, and a utopian vision of an enlightened society.

Heard has been credited—or blamed—for being the man who inspired Huxley to transcend his youthful cynicism and embrace more spiritual and religious themes. W. Somerset Maugham, who moved to Hollywood in 1941, mocked Heard behind his back, bemoaning the damage he’d done “to our great English literature” by luring Huxley and Christopher Isherwood (best remembered for Goodbye to Berlin, on which the movie Cabaret was based) off to California and into the vagaries of spiritualism.

Trabuco College of Prayer, which was paid for by money Heard had inherited, was a place to put his eclectic philosophy into practice. Twenty-five men and women—including Heard, Christopher Isherwood, and Isherwood’s cousin Felix Greene, who provided the organizational expertise—gathered in 1942. They would live under Heard’s spiritual direction, strangely isolated in a world that seemed to be tearing itself apart. Heard was convinced that the only way to save civilization was for humanity to spiritually evolve, one soul at a time. “Humanity is failing,” he preached. “We are starving—many of us physically, all of us spiritually—in the midst of plenty. Our shame and our failure are being blatantly advertised, every minute of every day, by the crash of explosives and the flare of burning towns.”

Such an antiwar stance was hardly popular at the time. In fact, Heard and Huxley had been facing criticism since 1939 over their decision to stay in California while Nazi bombs rained down on London.

Then there were differences of opinion over lifestyles. One of Heard’s rules was that those living at Trabuco remain celibate. This asceticism was at odds with the Bohemianism of some members of the group. Eventually Greene had a falling-out with Heard and ran off with Elena Lindeman, an actress who had taken up residence at the college. It fell to Heard to manage the organization—not his strongest skill.

The end of the Second World War brought a rush of recruits to Trabuco, including a number of pacifists freed from alternative service. But the monastery never really found its footing. Most war veterans were eager to get on with their lives—to go to a real college; to get a job and buy a house. The great post-war economic boom was on. Heard’s ascetic program of meditation and simple communal living could not compete with the creature comforts of conspicuous consumption.

By the time Huston Smith hitchhiked from Denver to Los Angeles and then made his way to Trabuco College, the experiment was in its final months of existence. Smith arrived shortly before supper, finding only a small group of men and women remaining. They set out an extra plate on the kitchen table and welcomed Smith into the fold. They ate their simple meal, listening to Heard give a little talk on the theology of the “desert fathers.”

“After supper, Gerald led me out to a promontory,” Smith recalled. “We sat on a rock and looked out over the canyon. I realized I had nothing to ask the man.”

Smith spent the night. The next morning, as he was getting ready to leave, Heard asked him if he was married. “With a wilting heart,” Smith recalled, “I said, ‘Yes. I’m married.’ My heart was wilting because at the time I really wanted to become a monk, to give up everything and study meditation.”

But that was not to be. Smith had his young family to consider, and he was about to begin a new teaching job at Washington University in St. Louis. And before long, Smith began to have second thoughts about Heard’s all-encompassing theory about the mystical destiny of mankind.

Huston Smith’s long academic career would include 15 years as a philosophy professor at MIT, at which time he helped Timothy Leary begin his infamous exploration into the spiritual potential of psychedelic drugs. Smith would also teach at Syracuse University as the Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion, leaving there as Distinguished Adjunct Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus. His university life would eventually return full circle to Berkeley, where Smith ended his teaching career as a Visiting Professor of Religious Studies. In between, he collected a dozen honorary degrees and published 15 books, including a 2009 autobiography titled Tales of Wonder—Adventures Chasing the Divine.

Today, sitting in his home in Berkeley, Smith has to laugh at his youthful exuberance about Gerald Heard. “It sounds silly now,” he said. “You wonder why someone would stay up all night with a book like that, but I was young and gullible. I thought about it some more and realized that there was very shaky evidence to support Gerald’s ideas. Sure, there were some people who have a talent for mystical experience, but there is no real evidence that that is happening across-the-board. There is no evidence pointing to an evolutionary wave leading us all toward mystical consciousness.”

Perhaps not, but it’s an idea that won’t go away. It’s one of the founding myths of the so-called New Age movement and the counterculture spirituality that took hold in the 1960s and 1970s. And it’s evident today, though it may take some digging to find it, given that headlines point to rising religious fundamentalism among Muslims, Christians, Jews and other true believers. There seems to be less peace and love, and more holy war, more religious intolerance.

Perhaps. It’s hard to ignore those noisy and violent pockets of religious extremism—but surveys of the American religious landscape paint a different picture. They show increased tolerance. According to the 2008 Pew survey, 70 percent of Americans affiliated with a religion or denomination said they agreed with the statement “many religions can lead to eternal life.” Even a surprising 57 percent of those calling themselves “evangelical Christians” believed there was more than one way to heaven.

Another Pew survey in 2009 showed that 65 percent of Americans express belief in or report having experience with at least one of the following spiritual concepts or phenomena: reincarnation, astrology, “spiritual energy,” yoga as spiritual practice, the “evil eye,” making spiritual contact with the dead, or consulting a psychic.

The American Religious Identification Survey 2008 found that those who claimed “no religion” were the only demographic group that grew in every state within the last 18 years. Between 1990 and 2008, the number of those who claimed no religious affiliation nearly doubled, from 8 percent to 15 percent. Yet the majority still pray, meditate, or believe in God.

Many are, in other words, spiritual but not religious. They are more likely to practice mix-and-match spirituality, to take a little from East and West, to go to church on Sunday and the yoga studio on Monday. They may be more interested in religious experience, and less concerned with religious dogma.

Not unlike the curriculum at Trabuco College of Prayer.