I am probably a familiar type to you. I went to college, got a master’s degree, started a career, married, and had my first child late, at 35. I was working as editor-in-chief of a fiction magazine called Zoetrope: All-Story when I became pregnant. The magazine, founded and published by Francis Ford Coppola, had long struggled to get a financial foothold. Under my editorship it achieved just shy of breakeven and earned a number of literary awards. In my last trimester, however, I found myself fighting for my job. During the last month of my pregnancy, on the day of my baby shower, I was fired.

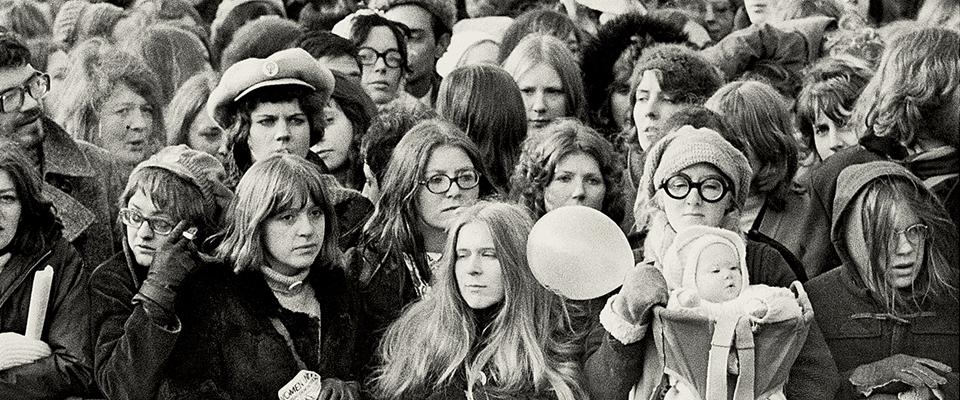

When I was pregnant, I also was the main breadwinner. My husband had just finished his Ph.D. and was on the academic job market. Not only did I have to hustle to find another job while hiding the fact that I was a breast-feeding humanoid, I had to threaten a lawsuit in order to extend my health insurance. I won. Yet I could see I already had lost. My mother’s generation—the Gloria Steinem generation of equal opportunity feminists—had fought and failed to create a system for working mothers, i.e., affordable day care for infants and toddlers, preschool for kids, and aftercare for school-age children. Instead, we have ended up with three months of maternity leave, 16 days of vacation, and a hodgepodge of “choices” that depend on whether we have a man, money, or family to help us along.

I was raised by a feminist and pretty much always considered myself a feminist. But “feminist” didn’t mean much to me until I was booted out of my office carrying 30 pounds on my belly. Looking back, I now find it spectacularly ridiculous that I was oblivious to a key battleground of American feminism: child care, with its barnacled tentacles around labor, class, and biology.

Americans have lots of opinions about working moms. Yet regardless of how they feel, 71 percent of those mothers are working outside the home, according to Pew Research’s latest numbers. And regardless of whether taxpayers think the government should subsidize child care, the cost of that child care is skyrocketing and creating seeds for downward economic mobility. Vox reported in August that child care costs are growing at nearly twice the rate of prices economywide. A 2013 report from Child Care Aware noted that as of 2012, in 31 states and the District of Columbia, day care is more expensive than one year of public college tuition—and that was among a cohort of faculty, people with the highest levels of education.

Today more than 40 percent of first-time mothers are unmarried and more than half split from their mate by the time their child is 5.

For people with less education and lower incomes, the news is much worse. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports that only one in six federally eligible children received child care assistance in 2006, the most recent year for which data are available. In the Golden State, according to a June 2014 study from the California Budget Project, funding for child care and preschool was cut by roughly 40 percent (after adjusting for inflation) compared to 2007–08. The result? Approximately 110,000 child care and preschool slots disappeared—a decline of nearly one-quarter since the Great Recession. There are just too many studies to cite here showing that when parents can’t find affordable child care, they give up working or looking for work.

Even at Berkeley, mecca of progressive politics, full-time day care for infants is $2,060 a month, $1,846 for toddlers, and $1,528 for Pre-K. Subsidies have never been available to faculty, staff, or students unless their income is below poverty level. And when government money does flow to care for children of poor students or staff, “it doesn’t cover half of what it costs to provide services,” said Mary-Ann Spencer Cogan, director of Human Resources and Organizational Services in UC Berkeley’s Residential & Student Services Program.

The only time the United States got anywhere near a comprehensive, universal system of birth-to-12 child care was when the whole nation was at war. In 1943, The Lanham Act created a system of all-day, government-subsidized child care centers that enabled women to take men’s places in fields, factories, and offices. The centers were affordable and wildly popular, according to a 2013 study by Arizona State University Professor Chris M. Herbst. He found that more than half a million children passed through the centers between 1943 and 1946, costing the U.S. government nearly $100 million (in 1940s dollars). Then the war ended and the centers were shut down. The issue remained largely moribund until 1971, when President Nixon vetoed the Comprehensive Child Development Bill, which would have created a national day-care system, largely for single parents.

In our current polarized and debt-rattled government, such a bill is unlikely to be resuscitated. But it would make a lot of demographic sense. Today more than 40 percent of first-time mothers are unmarried and more than half split from their mate by the time their child is 5. Meanwhile, evidence is mounting for the social and economic benefits of child care. A large body of scholarly research indicates that child care and preschool availability positively affects women’s employment options, professional advancement, and overall family economic security—and is a proven means to ensure school readiness among children. And better-paid women put more tax dollars into government coffers.

Arlie Hochschild, professor emeritus of sociology at UC Berkeley, has been writing around these issues for decades. In the new afterword to her 1989 book, The Second Shift: Working Parents and the Revolution at Home, she argues that the lack of affordable day care is a significant part of “the stalled gender revolution.” Hochschild says the culprit for this stalled revolution is not any one group, but a system.

“American capitalism over time embraced empowerment and sidetracked care,” she writes. “So in the absence of a countermovement, care has often become a hand-me-down job. Men hand it down to women. High-income women to low-income women.… The big challenge in the years ahead,” Hochschild concludes, “is to value and share the duties for caring for loved ones.”

What we have is elite women (and men) blathering on about choice, and billionaire executives passing themselves off as role models for working women, while refusing to acknowledge, let alone celebrate the women who help raise their children and manage their homes.

Unfortunately, most Americans don’t talk about the tensions among care, economic mobility, and female empowerment the way Hochschild does. The narrative I tend to hear is of middle- and upper-class women who choose between staying at home to care for their kids or remaining on the job and spending spectacular amounts of money on nannies, day cares, preschools, summer and holiday camps, and afterschools. This summer, my husband and I spent more than $2,000 a month on summer camp for our two kids.

Nonetheless, I see myself as lucky. Since Zoetrope, I’ve had a string of excellent supervisors and employers who have given me the flexibility I need to earn money and raise young children. But I remain pissed off about what happens to many other mothers.

When my daughter was 10 months old, I landed a job as an editor at the San Francisco Chronicle. Through Craigslist, I hired a new mother who traded in her job as a social worker to care for her infant son and my daughter. Jen quit working for one simple reason: Her day care costs were wiping out her income. I found her choice unfair, but the results were clear: My earnings and savings went up, and Jen’s went down. When the time came for preschool, I could afford to send my daughter to a good one. Meanwhile, Jen and her husband, also a social worker, had accumulated no savings, could not afford preschool, and went broke. Within a year, they fled San Francisco and moved in with relatives on the East Coast.

What is to be done? If we are stuck with a system that privileges small government (except for military expenses) and low taxes (particularly for the rich), we certainly will never be able to afford subsidized childcare. And if we continue to uphold a corporate culture that pushes workers to sacrifice family time for continued employment and/or higher earnings, care for children will remain in a vise. This vise, as Hochschild points out, devalues human connection and care. It also ignores the vast demographic changes in employment and American families over the last 40 years, and can be used by conservatives and traditionalists to blame women and poor people for society’s failings.

Feminism isn’t a prominent social movement in this country anymore. And one reason for this is blazingly clear: We don’t have an affordable, taxpayer-subsidized system of infant-to-12 child care that levels the playing field for all women, their partners, and their children. What we have is elite women (and men) blathering on about choice, and billionaire executives passing themselves off as role models for working women, while refusing to acknowledge, let alone celebrate the women who help raise their children and manage their homes.

I don’t entirely blame my mother’s generation for eliding or giving up on creating a system of child care. The political tides have been against them. But it scares the heck out of me that consciousness-raising circles have devolved into Lean In circles (as Sheryl Sandberg calls her female empowerment groups)—and that many women and men have come to accept the status quo.

My plea to the remaining feminists out there is this: Let’s find some class solidarity and make government-subsidized child care a campaign issue. Let’s identify and vote for candidates who see affordable child care as a legislative necessity. Such family-friendly demands would make sense to low- and middle-income women. They would bring more people back into the feminist fold, and they might even revitalize a movement.

Tamara Straus is editorial director of the Blum Center for Developing Economies at UC Berkeley.

From the Winter 2014 Gender Assumptions issue of California.