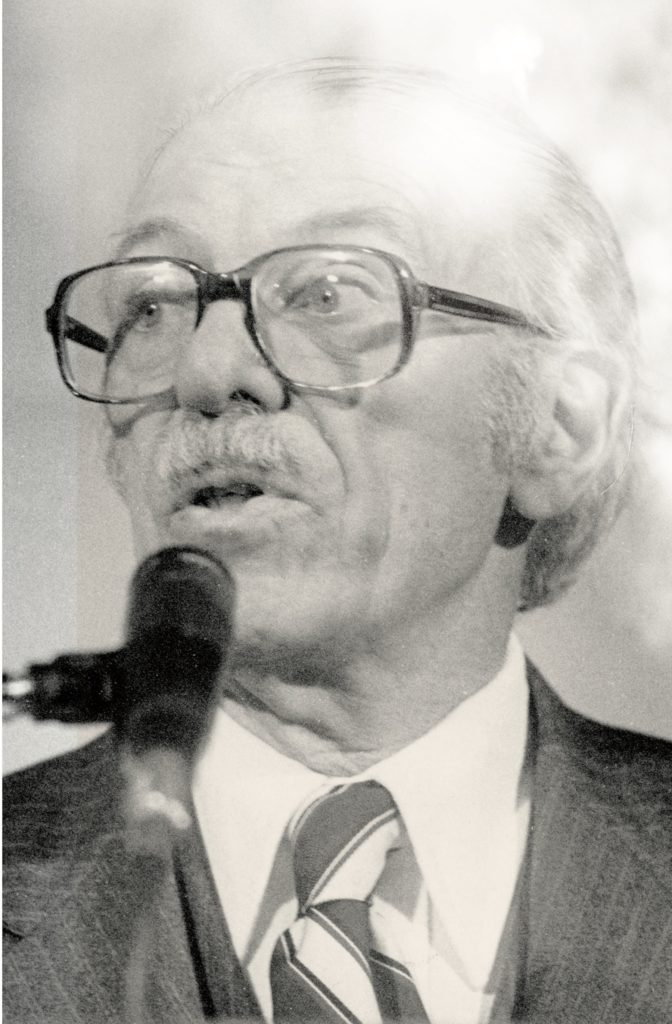

Berkeley biochemist Tom Jukes was an ardent conservationist and life member of the Sierra Club, but he just didn’t get 1960s environmentalism. The thing that bugged him most about the movement was its “emotional binge” against the pesticide DDT.

Environmentalists claimed DDT was killing wildlife and making people sick. Jukes, who had spent the war years developing lifesaving antibiotics, knew that nothing had done more to save human lives. DDT had prevented famines and saved entire countries from insect-borne diseases like malaria. So he decided to publicly come to its defense. “The DDT fight is a foretaste of the new Dark Age that is about to descend on the world,” he explained to a friend. “Truth is disappearing from scientific debate.”

He began to spread a few favored talking points: Environmentalists were unscientific, their capacity for reason was eclipsed by emotionalism, and their fight against DDT in particular was elitist and antihumanitarian. Reporters, producers, and politicians soon sought his contrarian opinions in droves.

As it happened, his talking points also caught the attention of the new conservative think tanks and foundations that were beginning to form. When one of them, the American Council on Science and Health (ACSH), named Jukes to its board, he accepted the post—not knowing that in doing so he was getting swept up in a decades-long, industry-funded crusade to shift the country rightward. Long after DDT was banned—decades later, in fact—he kept defending the chemical, with ACSH and other industry-funded groups happily spreading his views far and wide.

In Berkeley, Jukes spent his weekdays in the lab and his weekends in the mountains. He eventually cofounded the Sierra Club’s Sacramento chapter.

Jukes first arrived at Berkeley in 1933, with a doctorate in biochemistry from the University of Toronto, earned in the same lab where Frederick Banting and Charles Best had codiscovered insulin. Their legacy, he often said, had imprinted on him the idea that science stood in service of humanity.

In Berkeley, Jukes spent his weekdays in the lab and his weekends in the mountains. After he took a faculty position at Davis in 1934, he eventually cofounded the Sierra Club’s Sacramento chapter. Even after moving to New York for a wartime job at Lederle Labs a few years later, he went out West every summer to climb. Eventually he founded the first Sierra Club chapter east of the Rockies.

At Lederle, Jukes discovered that folic acid was a key vitamin. Antibiotics, he discovered, promoted livestock growth; the finding transformed meat production in the United States. He spent some time studying drugs to treat cancer, and then, in 1959, he got a call from Sierra Club Executive Director David Brower back in California. Brower wondered if Jukes’s employer, Lederle, might fund a Sierra Club book of wilderness photos by their mutual friend Ansel Adams. But Jukes found the book’s text “weird”; he thought it “attacked” synthetic fertilizers and medical research and made it sound as if using science to prevent hunger and disease was incompatible with conservation.

“I began to suspect that something very funny was happening in the Sierra Club,” he said.

Jukes felt his suspicion confirmed a few years later, when nature writer Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring, about the hazards of pesticides, was published. The Sierra Club rallied behind the book, but he found it full of inaccuracies, misleading statements, and hyperbole. He was most disturbed by its attack on DDT, which omitted discussion of how many lives the pesticide had saved.

He decided to correct the record with an article for the Sigma Xi journal American Scientist. He credited DDT with the ability to control a list of 30 diseases—malaria, typhus, dengue, plague, and cholera among them. He dismissed its hazards as negligible. He compared the “alarmist” fears of people who worried about pesticides in their food and environment to the “anti-scientific” measures fostered by Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union. “At stake is no less than the protection of the free world from hunger and disease,” he wrote, not immune from hyperbole himself.

The seven-page article forged his reputation for controversy. The journal’s editors were flooded with angry letters and canceled subscriptions. A feud between Jukes and Brower erupted. Brower dismissed Jukes’s arguments by pointing to the chemical industry’s “enormous” finances. Jukes called Brower a “vigorous neo-Luddite”—and spent the next two decades denying that DDT manufacturers paid him for his views.

“From then on,” he later wrote, “I felt, and still feel, that it is my duty as a scientist to do what little I can to bring the facts about DDT before the public.”

Jukes wasn’t the only one called to action by Silent Spring. Carson appeared on television and before Congress, her book reviewed and debated in newspapers and magazines all across the United States. President John F. Kennedy asked his Science Advisory Committee to investigate the book’s claims that pesticides were destroying bird and fish populations and contributing to human disease, potentially even cancer, as Carson had implied. Congress launched its own investigations. Jukes, meanwhile, moved back to California, for a faculty position at Berkeley. There, too, the governor had convened a special pesticides committee and lawmakers were tied in knots over how to respond to Carson’s claims.

In 1966, a group of Long Islanders decided to sue their local mosquito commission to stop it from using DDT. The group was incorporated under the name Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) the following year, and began filing lawsuits to stop the use of DDT and other pesticides in other states, too.

In Wisconsin, EDF got the state’s Department of Natural Resources to hold public hearings to determine whether DDT was a harmful pollutant. The hearings, which began in late 1968, became a national media event. Journalists jammed the State Capitol. Students held demonstrations outside, calling themselves DDT Commandos. They squirted spray guns at the trees and carried signs that said “Liberate the Ecosystem” and “Ban the Bug Bomb.”

Jukes, following the news from afar, was appalled. EDF’s young attorney grilled respected chemists and toxicologists without showing them a modicum of respect. EDF’s lead scientist Charles Wurster had published papers on DDT’s harm to wildlife—in the revered journal Science—that Jukes nonetheless found egregious. Wurster’s main scientific “achievement,” Jukes said, was “to collect a handful of dead robins” and call it “a nationwide slaughter of millions.” The hearings, he concluded, were a “circus.”

When the hearings examiner found that DDT was in fact a pollutant under Wisconsin law, Jukes decided to take his DDT defense to a new level. On a warm afternoon in June 1969, he called a press conference outside Berkeley’s Faculty Club. He acknowledged that DDT had its problems: As a persistent chemical, it stayed in the environment long after it was sprayed. And homeowners were spraying far too much of it in their homes and gardens: 140,000 pounds a year in California alone. But DDT bans—one had been proposed by Berkeley Assemblyman William Byron Rumford, in fact—went too far in his view. “Whether we like it or not, millions of people are alive and healthy because of DDT,” he said. Banning it was tantamount to “genocide.”

That message stuck, picked up by news wires and carried in papers all across the state and all the way to the New York Times. Emboldened, Jukes proposed a two-man publicity campaign to his good friend and fellow alpinist J. Gordon Edwards, a biology professor at San Jose State. “We are faced with an anarchist-led … revolt against science that is gaining in intensity,” he told Edwards. He believed that EDF had swayed public opinion by controlling the media; he called it “the Rachel Carson technique” and proposed that he and Edwards adopt it. “Free speech is the property of those who control the mass media,” he wrote.

Edwards created a course on DDT at San Jose State; Jukes praised it as “the very essence of academic freedom of inquiry.” Edwards then pulled off his own version of a press conference, taking a box of DDT powder with him to an interview with San Jose State’s public relations director. While answering questions about DDT, he snacked on it straight from the box. The next day, he was in dozens of newspapers and footage of him eating the pesticide aired all over the state.

Jukes, meanwhile, tracked down every anti-DDT article he could find and wrote to editors and publishers in response. He let nothing go, whether it was in the New York Times, Science—or the Daily Californian. He wrote to textbook publishers, scientists at the World Health Organization, and regulators at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Federal Communications Commission. He wrote to state lawmakers. He wrote to lawmakers in Congress. He wrote to Vice President Spiro Agnew and President Richard Nixon.

“There is at least one unequivocal effect of DDT,” wrote the author of an article attacked by Jukes. “It causes T.H. Jukes to write an inordinately large number of letters defending it.”

One of Jukes’s most potent talking points was that DDT bans, by reverberating from state to nation and nation to globe, would result in starvation, disease, and death for millions of people, the vast majority of them poor; preventing such deaths was America’s global duty, as he saw it. He also argued that environmentalists ignored other explanations for the wildlife destruction they attributed to chemicals; that they focused on pesticides’ hypothetical cancer risks while ignoring the real cancer risks from smoking and sun exposure; and that they refused to acknowledge pesticides’ benefits. Scientists aligned with the environmental movement, he told Senator Gaylord Nelson, had lost their capacity for reason, allowing nostalgia and emotion to reign in its place.

“Undoubtedly, pesticides create ecological problems for wildlife,” he said. “So do agriculture, freeways and human beings.” He posited himself as one of the few scientists in the nation—possibly the world—with the capacity to remain objective on the issue of DDT.

On a flight from San Francisco to New York in early 1970, Jukes wrote to Edwards to update his friend on the next front in the DDT fight. The EDF, Sierra Club, and Audubon Society had jointly filed a petition with the USDA, asking the agency to cancel the pesticide’s registration—to ban it, as he had feared. Knowing that the petition would likely force the agency to hold hearings on the chemical, he told Edwards, “I am going to offer to appear for the USDA if needed.”

Before the year was through, the USDA’s responsibility for pesticide reviews and regulation in general was handed to the new Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), created by the Nixon administration. In 1971, EPA Administrator Bill Ruckelshaus, a former Republican congressman from Indiana, announced that the new agency would hold a Consolidated DDT Hearing to respond to a set of petitions, lawsuits, and hearing requests filed over the previous two years.

Jukes offered to testify on behalf of the National Agricultural Chemical Association. In the meantime, he kept up his media campaign. Jukes and Edwards banded together with a half dozen other colleagues from across the country to launch an organization they called Sponsors of Science. Norman Borlaug, the agricultural scientist who won the 1970 Nobel Peace Prize, joined them—and it was especially easy to get him in the papers. The New York Times devoted an entire article to Borlaug’s statement that a DDT ban was “based on emotion, mini truths, maybe truths and downright falsehoods launched by full bellied philosophers, environmentalists and pseudoecologists.”

But Jukes alone did more than anyone to spread the idea that DDT’s foes, especially environmentalists, were hypocrites. He was sure that members of the Sierra Club, in particular, consumed more fossil fuels and paper than the average American. Environmentalists generally, he complained, were all too ready to jump in their cars to drive to a protest and retreat to their air-conditioned homes afterwards. They were “haves” insensitive to the needs of the world’s “have-nots,” guilty of a form of “imperialism” that harmed the then-called Third World.

When Jukes took the stand in the Consolidated DDT Hearing, attorneys for the petitioners sought to remove him. They pressed him on the original research he had conducted on DDT, until he had to admit that he had not done any. Hearing examiner Edmund Sweeney told Jukes he was “reluctantly” excused.

At the end of the hearing, Sweeney decided not to cancel DDT’s registration. Two months later, in June 1972, Ruckelshaus overruled him. The Sierra Club and its fellow petitioners celebrated, hailing DDT’s ban as an environmental victory. Jukes mourned the decision. And he was most rankled by environmental groups’ argument, in the hearing, that DDT was a possible carcinogen. To Jukes, the evidence linking the pesticide to cancer at the time—rodent studies and a few inconclusive studies in people—was so scant it was meaningless.

The DDT Ban didn’t stop Jukes’s crusade. Over the next several years, he wrote articles disparaging the “organic food cult” as well as the “propaganda” and “misinformation” it spread about the hazards of pesticides and other chemicals used in food production. They stirred up a level of controversy he was used to by now. They also caught the attention of Fredrick Stare, the widely revered founder of Harvard’s nutrition department.

Stare was writing a book with one of his star graduate students, Elizabeth Whelan, and Jukes’s arguments squared perfectly with what they wanted to say: that Americans’ food fears were irrational fads, unsupported by science. Their book, Panic in the Pantry, was published in 1975. Whelan was so good at promoting it that she soon had a syndicated radio show and nonstop invitations to write for popular magazines. She and Stare saw an opportunity: They founded an organization dedicated to advancing the ideas that chemicals in food and the environment were safe and that existing regulations on both needed to be rolled back. They called it the American Council on Science and Health.

ACSH got off the ground in 1978 with funding from a handful of conservative foundations devoted to moving the country’s politics to the right. Among them was the John M. Olin Foundation, whose founder was a longtime manufacturer of DDT. To establish ACSH’s scientific bona fides, Whelan and Stare gave ACSH a Scientific Advisory Board in addition to the standard Board of Directors. They invited Jukes to join both—as their “pesticide expert.” Despite not having carried out any pesticide research, Jukes readily joined the Scientific Advisory Board, along with Edwards and Borlaug.

With Whelan at the helm, ACSH quickly became journalists’ go-to source for stories on health in the late seventies and early eighties. Whelan herself soon had a daily spot on the new Cable News Network and a phone endlessly ringing with requests from outlets ranging from the MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour to the Wall Street Journal. “We don’t feel a chemical is guilty until proven innocent,” she liked to tell reporters. “We don’t think a chemical should be banned at the drop of a rat.”

Though Whelan and Stare initially touted ACSH as independent, within a few years, generous checks were coming in from a long list of companies, from Coca-Cola and Frito-Lay to Dow Chemical and Exxon. The companies valued the organization’s messaging: that pesticides, food dyes, artificial sweeteners, and other chemicals were perfectly safe, and that those claiming harm were untrustworthy alarmists.

While Whelan held the spotlight—profiled in People, debated on Larry King Live, and quoted in all the top newspapers—Jukes and his fellow board members supplied ACSH with ideas and scientific arguments to put before the public: that smoking, sun, diet, and lifestyle caused more cancer than chemicals did; that carcinogens were found naturally in foods, including every course of Thanksgiving dinner; that chemical levels detected in food were so low they were equivalent to zero; and that animal studies proved nothing about a chemical’s potential to cause cancer in people.

DDT, long since replaced by other pesticides, became less and less relevant as the years went by. But in ACSH’s hands, its story lived on as a morality tale. As studies published in the late seventies and eighties failed to firmly connect it to cancer, ACSH and its supporters described DDT as the harmless chemical whose unjustified ban caused more harm than good. DDT’s story became, for the pro-business camp, the quintessential example of regulation gone wrong.

On the 20th anniversary of DDT’s ban, in 1992, ACSH held a Washington, D.C., press conference featuring Jukes, Edwards, and ACSH Vice President Edward Remmers. Jukes, 86 by then, was relatively quiet. Remmers, taking the lead, shared Jukes’s decades-old message with a grim update. DDT’s ban was still putting millions worldwide at risk of malaria, he said, but it was also contributing to the spread of AIDS in parts of Africa, where children hospitalized for malaria received blood infusions contaminated with HIV. The ban was guilty of “genocide,” he said. Edwards repeated the phrase.

Jukes’s writings slowed over the next few years, though he continued mountaineering into his nineties. In 1999, the year he died, delegates from around the world met to hammer out a global treaty to ban 12 toxic chemicals known as persistent organic pollutants. DDT was on the list. And it was the only chemical that had the delegates locked in heated debate.

A group of nearly 400 health scientists had signed a letter to delegates advocating for a DDT exception in countries with high malaria rates. The letter caught environmental scientists and advocates at the negotiations off guard, pushing one particularly rancorous meeting straight through until dawn, when the delegates finally agreed that the chemical could still be used in places where the spread of malaria was uncontrolled.

No doubt, Jukes would have approved, but it’s anyone’s guess what he would have made of what followed. A man named Roger Bate, head of a conservative think tank in Jukes’s native England, found the feud between the health and environmental scientists ripe for exploitation. He drafted a proposal for a media campaign to spread the message that DDT bans were the reason so many people were dying of malaria in Africa. The campaign, funded by the tobacco industry, painted environmentalists as self-serving and undercut public confidence in environmental regulations generally. It was enormously successful: In the early 2000s, journalists from the evening news to the New York Times reported that it was time, as Nicholas Kristof put it, “to spray DDT.” Some commentators were more strident, likening the ban, as Jukes long had, to genocide; some accused Rachel Carson of having caused more deaths than Hitler.

Twenty years later, DDT bans in the United States and other Western nations remain in place. The idea behind Bate’s campaign—unlike Jukes’s—wasn’t to bring DDT back into use but to prove the supposed wrongs of liberal governance and rally support for free markets. The global treaty on persistent organic pollutants retains its DDT exception, which only a few countries use. Roughly 150 countries have ratified the treaty. The United States isn’t one of them.

Jukes championed the idea that DDT was safe; industry used his message to spread the idea that all environmental chemicals were safe.

Jukes took on other crusades over the course of his career—against the teaching of creationism in schools, for example, and against Linus Pauling’s views on vitamin C. As gratified as he would have been to see his DDT defense find traction in the new millennium, though, he likely would have been taken aback by Big Tobacco’s role in it. Jukes championed the idea that DDT was safe; industry used his message to spread the idea that all environmental chemicals were safe. Jukes believed he was defending all of science in defending DDT—but the industry players who spread his message did so to undermine it. They called research like that documenting DDT’s harms to animals—and eventually people—“junk science.”

While Jukes would have agreed that certain science was “junk,” he surely would have used the term far more selectively. And he likely would have continued to pride himself on doing so independently.

But in truth, he took that particular principle only so far. ACSH had no plans to pay him, but Jukes insisted on compensation, and Stare eventually conceded. Privately, Stare told the staff at ACSH, “I always have tried to avoid arguments with Tom!” Jukes was one person he did not want to tangle with.

Historian of medicine Elena Conis, M.S. ’03, M.J. ’04, is a professor in the Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and the Department of History and the author, most recently, of How to Sell a Poison: The Rise, Fall, and Toxic Return of DDT (Bold Type Books).