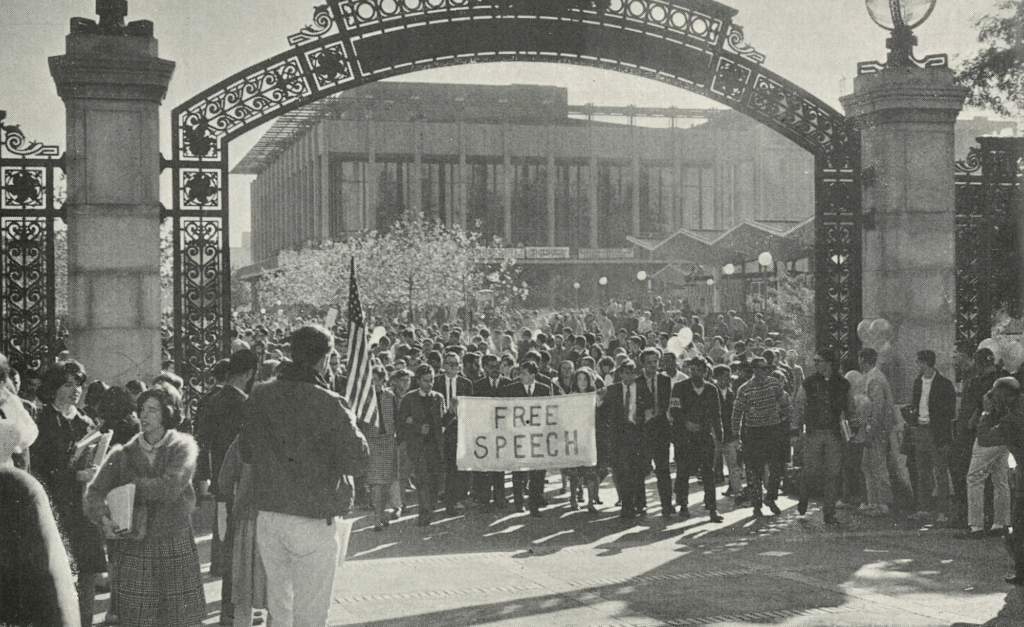

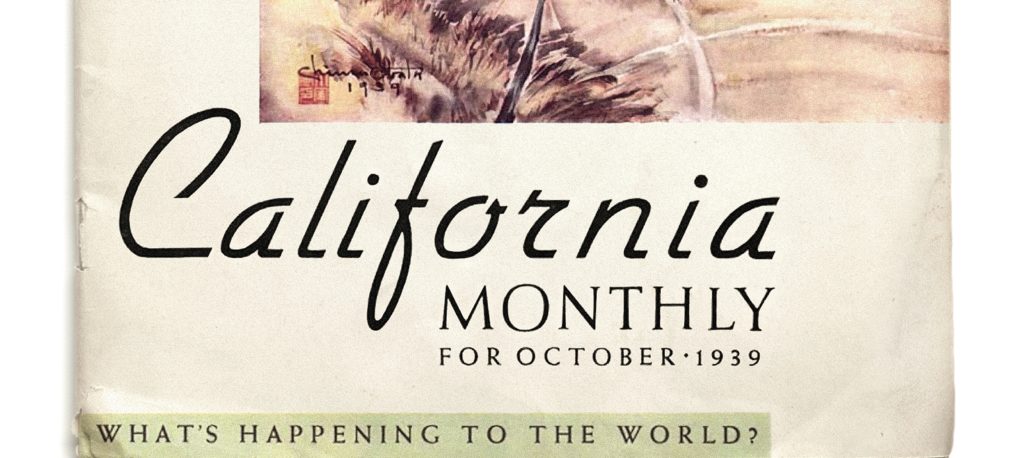

Sixty years ago, in the fall of 1964, the staff of this magazine—then called California Monthly—had the foresight to drop everything to cover a student uprising that was then roiling campus. The Free Speech Movement scarcely had a name, but the Monthly was on the job.

Assistant Editor Don Kechely ’55 shot photographs, many of which are still among the most iconic and familiar images from that time. Sociology grad students Max Heirich, M.A. ’63, Ph.D. ’67, and Sam Kaplan, M.A. ’66, provided historical context on campus protests dating to the 1930s in a long piece titled “Yesterday’s Discord.” Pertinent documents on campus regulations were provided to readers in an appendix. UC President Clark Kerr and Acting Chancellor Martin Meyerson were afforded space for statements. At the heart of the issue was a chronology compiled by reporter Fred Gardner of the Berkeley Gazette, who was brought in to provide a detailed, blow-by-blow account of events as they unfolded.

Sample entry from October 2, 1964:

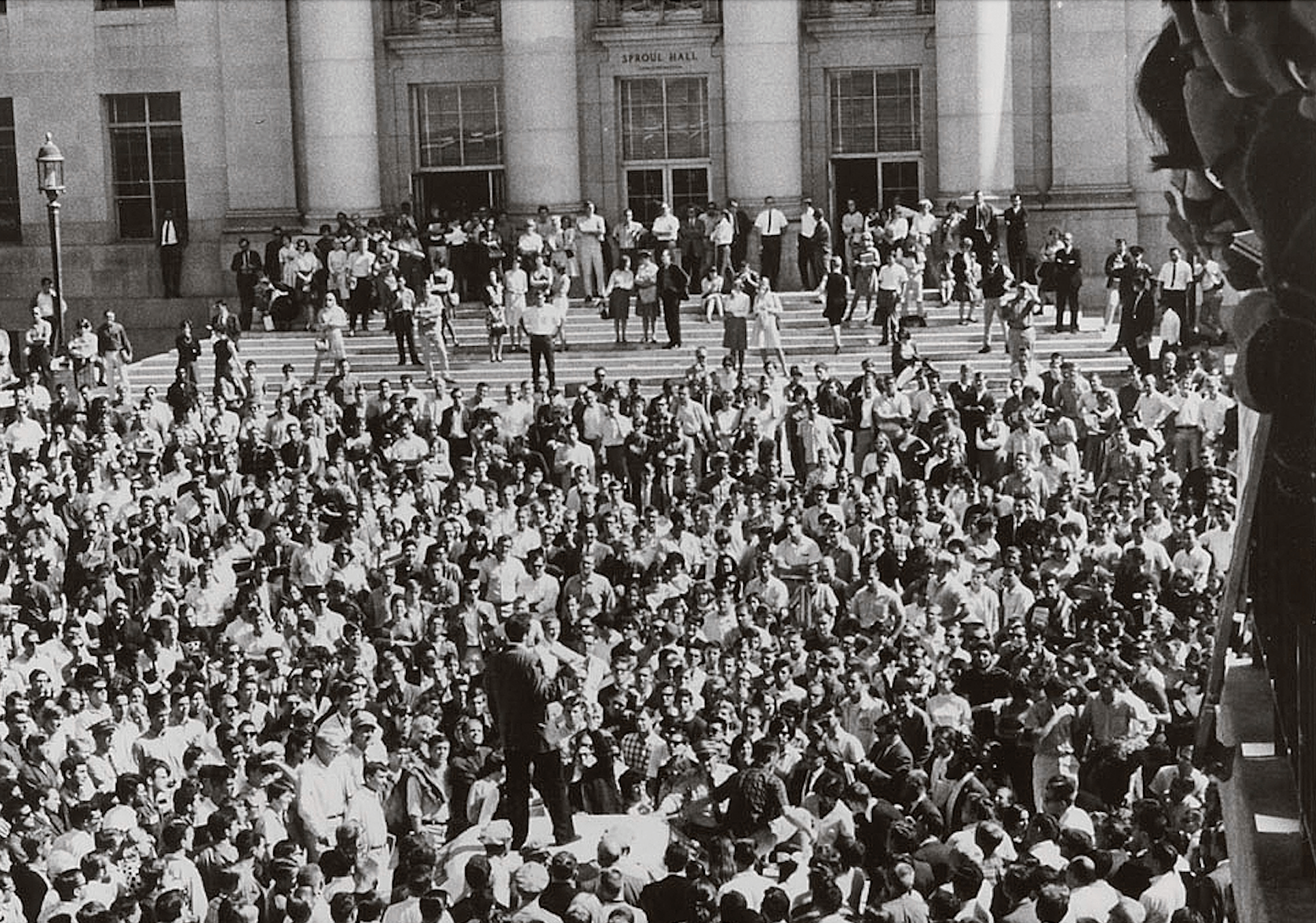

“At 1:30 a.m., as conflicts between demonstrators and anti-demonstration demonstrators threatened to erupt into a full-blown riot, Father James Fisher of Newman Hall mounted the police car. The crowd fell silent as he pleaded for peace—and got it.

“Demonstrations around the stranded police car, still containing Jack Weinberg, continued throughout the day. Sproul Hall was locked, except for one police-guarded door at the South end through which those with legitimate business inside could pass. A pup tent was pitched on one of the lawns. The entire mall area was littered with sleeping bags, blankets, books, and the debris of the all-night vigil.

“Speakers continued to harangue the crowd from the top of the sagging police car, gathering momentum as noon approached. At noon, lunch-time onlookers enlarged the crowd to close to 4,000 persons.”

For sheer attention to detail, this is first-rate reporting: the lone pup tent, the night’s cast-off detritus, the crowd swelling with the noon-hour curious, and, of course, the sagging cop car. And then we learn, on October 5: “In an effort to atone for the damage done to the police car during the Thursday and Friday demonstrations, the students began a collection of funds to help pay the $334.30 in damages.”

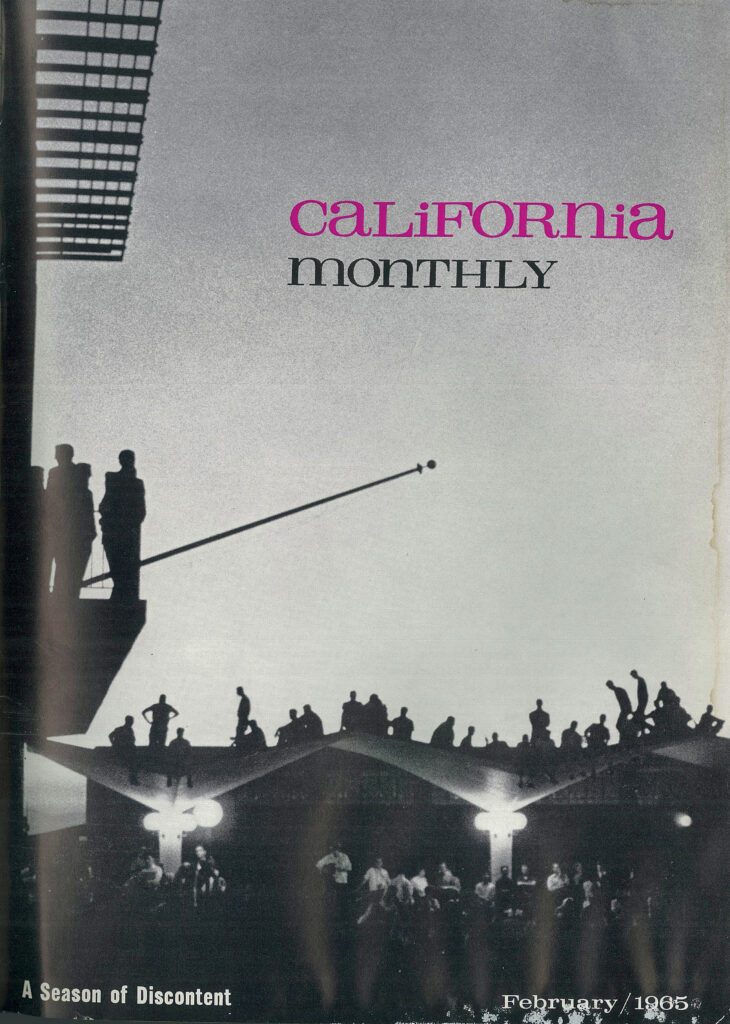

The resulting, 96-page issue of the Monthly appeared in February 1965. It was titled “A Season of Discontent.” Decades later, former campus spokesperson Ray Colvig ’53 would declare the Monthly’s effort the “most complete, important first account” of the Free Speech Movement. It was, he said, “an astounding piece of work, considering how little time there was to put it together.”

For the record, while Dick Erickson ’49, MBA ’50, executive director of the Alumni Association, was the titular editor of the magazine, the real credit for putting it together goes to Managing Editor Andrew Pierovich ’63. According to Dick Corten ’65, who contributed to the magazine at the time and would go on to become editor of the Monthly in the 1970s, “Andy was the guy who really produced that monumental FSM issue. That movement and season were like nothing this campus (or any campus anywhere) had experienced before, and, with a ton of help and a prodigious vision, Andy wrangled something huge and new: an authoritative record of a fast-breaking upheaval…. Analytical pieces and oral histories have been referring to and quoting from that thick publication for decades since.”

None of which should suggest that the accompanying editorial was approving of the student movement. In his editor’s note, Erickson lamented the “tragic events” that he found both “frightening and disturbing.” He closed his note with a call for input. “The interested and concerned voice of alumni and tax-paying citizens of the State must be heard.”

Readers obliged, and the March issue was filled with five pages of angry letters to the editor, many of which ran under headings like “Sickening News,” “Disgraceful Attitude,” “A Sense of Shame,” and “Ashamed and Disgusted.” Correspondents, almost without exception, demanded that punishment be meted out to the protest leaders. The most concise of these read: “As concerned alumni we urge strong action against FSM agitators. Alarmed over faculty’s position. Does Berkeley need a house cleaning? The situation is dismal. Let there be light.”

Twenty years later, however, many critics had relented, Erickson among them. In 1984, he told the Monthly, “All [that] the thinking student was saying in those days was: Politics is a part of the fabric of this country. It’s important to us.” He added, “I think the University’s a better place today because of what took place. I’m only sad that so much trouble had to take place before the changes could be brought into play. There was no doubt the rules were outmoded, that they should be changed.”

While Erickson’s comment did not make it into a 20-year retrospective on the FSM, his sentiments were echoed by some faculty and administrators who had softened their attitudes over time. Still, others were full-throated in their support, such as the late Berkeley historian Leon Litwack ’51, M.A. ’52, Ph.D. ’58, who said of the 1964 student movement: “I think few generations cared more deeply about this country. It was a generation that opted for the highest kind of loyalty. It defined loyalty to one’s country as disloyalty to its pretenses, a willingness to unmask its leaders, a calling to subject its institutions to critical examination. That, to me, is real patriotism.”