Kosar Eftekhari remembers the agent smiling before pulling the trigger. The 24-year-old student and actress was standing among thousands of Iranian protestors in Tehran when a security agent shot her in the face with a paintball gun. The attack left her bleeding and blinded in one eye. Eftekhari is one of countless Iranian civilians injured or killed during protests following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini, who was arrested for opposing mandatory hijab rules and died in police custody on September 16, 2022. Herm case sparked a global movement calling for the end of oppression against Iranian women.

Eftekhari’s story might have been lost to time or the digital ether. Instead, it made its way more than 7,000 miles away to Cal, where a small cohort of students in Berkeley’s Investigations Lab, a project of the university’s renowned Human Rights Center (HRC)—now celebrating its 30th year—pore over footage and testimonials shared by victims like Eftekhari.

It’s often tedious work.

On a Wednesday morning in February, half a dozen students sit around a long, wooden table, sipping coffee and squinting at their laptops, working on a deadline from the U.N. They have until Saturday to authenticate the materials they’re examining and create reports for each victim. “Can you see anything in

this one?” a student asks, turning her laptop to a neighbor. They lean over the screen, replaying a silent, colorless clip. No luck—the street could be anywhere in Tehran, and the video blurs as a car appears, making license plate identification impossible. “All right, I’ll go on to something else,” she says, sighing and clicking open the next file.

As campus extracurriculars go, this is hardly run-of-the-mill student fare. From their lab—a spacious room in an unassuming white house on Piedmont Avenue—the young researchers collect and analyze evidence of human rights violations and other horrors from the farthest reaches of the world, from Myanmar to the Brazilian Amazon.

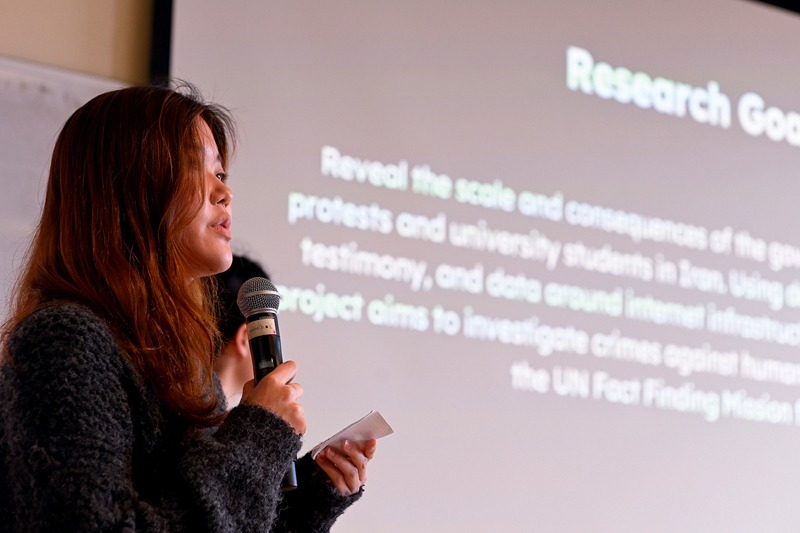

Needless to say, the work can also be emotionally taxing. Students spend hours each week closely inspecting often graphic snapshots of what may be the worst moments in people’s lives. The Iran project has been a particularly intimate experience. “This is the first investigation I’ve done where I’m dealing with victims’ names,” Madeleine Wong ’25, a second-semester junior and team lead, says. As a woman, the protest movement in Iran also feels personal to her. “That conflict stretches beyond religion and borders. It is about the suppression of women, the right to dress [how one pleases], the violent enforcement of laws.”

So far in the Iran investigation, the students have been able to verify roughly 126 instances of blindings. Over the course of eight months, the team busily reverse-searched images and cross-referenced news sources to determine the victims’ names, genders, and ages, and the time of the events. They scrutinized Google Maps to geolocate each incident. From this data, the students created full profiles of each victim, as well as an interactive timeline and map of where all the blindings took place.

Important patterns emerged from the data. The blindings were often deliberate; pellet guns were the most commonly used weapons, often fired at close range; the majority of the victims were younger than 30; both men and women were targeted, but women seemed to suffer the worst assaults.

Hundreds of students from a variety of backgrounds have joined the lab, which was founded in 2016. Collectively, the current cohort speaks nearly two dozen languages and dialects. All possess remarkable digital literacy, which is key in a world where social media provides invaluable intelligence, especially

from places where the state controls the media and censorship is common.

“The skills that our students have are in really high demand,” says Jess Peake, assistant director of UCLA’s Promise Institute for Human Rights, part of the larger University of California Digital Investigations Network. “This is a very new and emerging field. Even ten years ago we weren’t thinking of using social media information as evidence in the way we are now.”

“One of the things that I’m most proud of is the pipeline to practice that has been created through the Investigations Lab,” says Alexa Koenig, M.A. ’09, Ph.D. ’13, the HRC’s co–faculty director and a professor at Berkeley Law. Graduates of the lab have gone on to employ their expertise as investigators at

the International Criminal Court, various United Nations bodies, and the New York Times visual investigations team. “They’re able to get these really extraordinary opportunities and bring the best of Berkeley into these global organizations.”

In February, the HRC officially launched the Berkeley Protocol, the first international guidelines on the use of digital open-source investigations, which has already been used by outside investigators to verify information from the West Bank and Gaza. The HRC also applied the protocol in analyzing a subset of roughly 1.3 million pieces of digital content comprising the Iranian Archive, a landmark digital catalog launched in March, which may serve as evidence of crimes against humanity committed by the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Since its humble beginnings as a two-person team housed in the Townsend Center for the Humanities, Peake says the HRC “has really been a leader in the field. Their role in the development of this methodology and the employment of these tools in this way for accountability processes is really pretty tremendous.”

It’s also timely. At the February launch event for the protocol held at Berkeley Law, Volker Türk, the U.N. high commissioner for human rights, described living in “an era of war and peace,” with an unprecedented number of international conflicts and billions of people voting in elections this year alone. He warned of increased violence, oppression, and other human rights violations in times of political upheaval—and the necessity of organizations like the HRC. “It’s extremely important that we have good standards that apply on the type of evidence that is gathered and collected so that it can be used for criminal accountability,” he said.

Criminal accountability is key. Eftekhari’s testimony, along with that of more than 120 others, formed the basis for a damning report presented to the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva, Switzerland, in March. In response, the council voted to extend its Iran investigation for another year, a move that Koenig says is necessary for the next step in the process: making perpetrators answer for their crimes.

The U.N. has “an ability to potentially share information with governments who may now be interested in picking this up and getting some form of legal accountability within their country,” she says. For instance, “if perpetrators from the Iranian regime leave Iran and go to [other] countries, there’s a mechanism

already in place … so that these prosecutions can happen.”

The ultimate hope, Peake says, “is that national war crimes prosecutors’ offices will be able to use the archive to either build structural investigations or open universal jurisdiction cases against perpetrators of the human rights violations and crimes against humanity.”

Regardless of the outcome, the verification protocols and data analysis developed for the Iran investigation could very well be applied elsewhere, such as in Israel, Palestine, Ukraine, and Syria.

For all their diligence, the students may not see the results of their labor anytime soon—or ever. But they have come to understand that strong cases require strong evidence, and strong evidence takes time.

And so, back in the Investigations Lab, as the clock approaches noon, the students close their laptops and head to their next class. They’ve done as much as they can for today—but they’ll be back.