Do the majestic vistas of Yosemite National Park make you swoon? Are you besotted with the equally splendid landscapes of Yellowstone, Zion, the Smokey Mountains, the North Cascades and Rocky Mountain National Parks?

Thank UC Berkeley.

“Cal alumni had a major influence on both launching and maintaining the National Park system,” says Steven Beissinger, professor of wildlife ecology at Cal. “It’s no coincidence that three of the first four directors of the National Park Service were university alumni.”

Some national parks had been established in a hodgepodge fashion by the second decade of the 20th Century: most notably Yosemite, Yellowstone, Mt. Rainier and Rocky Mountain, along with a couple of national monuments. “But there was no broad supervisory service responsible for protecting resources and establishing standard policy,” says Beissinger, who’s in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management.

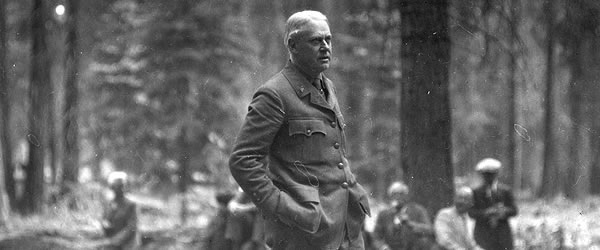

Then along came Berkeley alums Stephen Mather, class of 1887, and Horace Albright, class of 1912. A successful businessman who had developed and promoted the 20 Mule Team Borax brand, Mather was also a Teddy Roosevelt-style conservationist and outdoor enthusiast.

“Mather complained to then-Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane (a Berkeley drop-out) about the condition of the national parks,” Beissinger says, “and Lane told him, ‘Well, come to Washington and do something about it.’ So Mather ended up as Assistant Secretary of the Interior.”

There he was joined by his mentee, Albright. Hoping to generate some momentum for a full-fledged national park system, the two men convened a conference at UC Berkeley on March 15, 1915, attended by 75 scientists, conservationists, politicians, park administrators and resource managers. Berkeley alum Mark Daniels, class of 1908—later the first general superintendent and landscape engineer for the National Park Service—moderated the event. Some months later, Mather squired 15 national power brokers, including National Geographic Society publisher Gilbert Grosvenor, on a two-week horseback trip through the Sierra Nevada.

The “Mather Mountain Party,” as the lavish show-me junket was dubbed, apparently did the trick. Influence was applied, Washington lawmakers were charmed or otherwise convinced, and the National Park Service Organic Act won passage in 1916. The text of the bill elucidated the new agency’s mandate:

“To conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife (of the parks) and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by what means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations…”

The Berkeleyites then moved on to forging a broad ethos for the newly-minted agency. Resource protection was a given, but accommodations also had to be made for visitors. Daniels came up with the idea of national park “villages”—small, clustered camping and lodging developments that would have been dubbed “eco-friendly” had anyone been using that term back then.

Mather, Beissinger says, focused on transportation: “He knew there had to be decent access to the parks to build a sustained constituency, so he was instrumental in getting railroads and roads authorized and funded.”

Meanwhile Joseph Grinnell, the first director of UC Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, conferred scientific legitimacy on the national park mission. Most noted today for his surveys of California fauna, Grinnell had “an early vision of the parks as scientific laboratories,” says Beissinger. “He had seen the rapid changes that were occurring in California’s wildlands, including the disappearance of charismatic species such as the grizzly and the fisher. He recognized that an essential mission of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology had to be meticulous surveys of (wildlife) of the state and the West, and that the national parks were critical to that research.”

At the time of his work, Grinnell was highly praised for the quality and quantity of the specimens he brought back to the museum—specimens still widely used by international conservation biologists. But of equal significance, says Beissinger, was the rigorous process of field notation Grinnell developed—a method that remains the standard for field biologists today.

“Using the Grinnell method, specimens and notes complement each other incredibly well,” says Beissinger. “Grinnell had tremendous influence over science policy in the parks. He was one of the earliest advocates of ecologically-based park management, and that’s still the standard today. Further, he trained many of the first National Park Service biologists. They shared his vision and his methods.”

Mather and Albright became the first and second directors of the National Park Service. Berkeley alum Newton Drury was the fourth director, overseeing the service from 1940 to 1951. Other Berkeley alumni and academicians also contributed, directly or obliquely, to the agency. They include:

- Joseph LeConte, a professor of botany, natural history and geology, a co-founder of the Sierra Club, and one of Yosemite’s seminal researchers

- George Melendez Wright, who started the National Park Service’s wildlife division with his own funds and ran it for several years out of Hilgard Hall

- Ben Thompson, who conducted Fauna No. 1, the first comprehensive survey of wildlife in the national parks

- A. Starker Leopold, long-time Berkeley zoology professor and an advisor to the service on wildlife issues

- Ansel Hall, the first park ranger in Sequoia National Park, the founder of the Yosemite Museum, and the service’s first chief naturalist and chief forester

- Harold Bryant, who established the service’s interpretive program

“The University of California and the National Park Service had more than a relationship,” says Beissinger. “Really, the university was the engine that drove the Park Service forward.”

The university commemorated the centennial of the 1915 Berkeley conference on national parks with two events. A two-and-one-half day conference, Parks for Science: Science for Parks: The Next Century, was held March 25-27 to examine the role and mission of the National Park Service in the 21st Century. The spring 2015 Horace M. Albright Lecture in Conservation, America’s Two Best Ideas – Public Education and Public Lands, was held on March 26, featuring a conversation with US. Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell, University of California President Janet Napolitano, historian and author Douglas Brinkley, and UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks. All conference plenary sessions, including the Albright public lecture, can be viewed on the Berkeley You Tube station.