I arrived at UC Berkeley in the fall of 1980 set on earning my PhD in astrophysics, and left five years later with an English degree and a burning passion for writing and reporting. What happened? John Bishop happened. One brilliant teacher, kind and absurdly generous, lit an internal flare inside of me that illuminated my imagination from within, with arc-welder intensity.

“Release your genius,” Bishop told me and the other restless undergrads in his English 40 class in spring 1982, the emphasis being on “release.” We really only understood the admonition when we saw the way that Bishop devoted himself to every paper turned into him as if poring over the Rosetta Stone. His notion of genius was that which brings us together, not what set us apart. As Plato put it, “Do not train a child to learn by force or harshness; but direct them to it by what amuses their minds, so that you may be better able to discover with accuracy the peculiar bent of the genius of each.”

Bishop, 33 that year, had burning, intense eyes that would have been scary if he were not soft-spoken and halting, a man whose witty ripostes were always sly and roundabout. He was dreamy and understood what it was like to be an undergrad, sometimes starting a morning class by joking about needing time to get his spatial relations together. “Being asleep is easy,” he once told the Times. “Being awake is too. But the transitions between the two are ghastly.”

I recall a warm morning in class when a young woman asked if she could play a cassette tape, in lieu of reading aloud her expository essay, and Bishop nodded. Her recorded voice, sounding a little muffled, was soon ringing out: “I am a wet and sopping—” and she continued with sound effects she could only have provided in the privacy of home. Probably not quite what Bishop had meant by releasing genius, but he flushed, recovered himself, and mumbled some joke to defuse the tension in class.

I don’t have any of my essays from that class, which is probably a good thing, but I can still see the pages in my mind, drab typewritten lines enlivened by a forest fire of elaborate notations scrawled in red, most often Bishop’s effusions of enthusiasm. If he was dynamiting a half-baked idea, he tended to be more concise. When you threw something at him that felt fresh or fun or a little weird, his scrawl rounded corners. Submitting an essay to the man was like handing him a key to take residence inside of you.

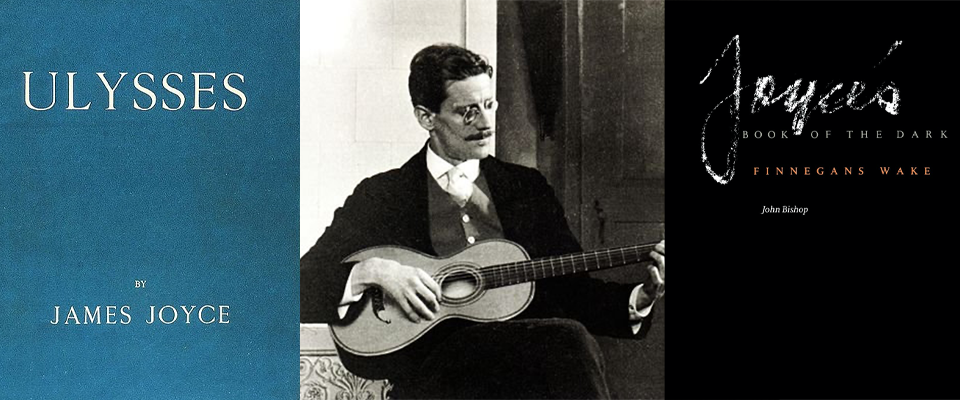

I remember wondering how he did it. How did he put so much into seeing the words we plodding students wanted to write, even when we didn’t quite know what they were? At a cost, I now realize. We all knew Bishop had devoted his life to James Joyce. We heard vague rumblings about a book he was writing on James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, and the rumblings continued for years.

I can still see the pages in my mind, drab typewritten lines enlivened by a forest fire of elaborate notations. Submitting an essay to the man was like handing him a key to take residence inside of you.

“I used to chastise him because he was having a hard time getting as much done as he could on his book,” recalls his friend, fellow English professor Mitchell Breitwieser, hired in ’79 along with Bishop. “I told him, ‘John, you’re writing more words on your students’ pages than they’re writing in their papers.’ … I don’t think he ever cut back.”

Colum Lynch and I both did our senior theses with Bishop, writing about Ulysses. Lynch, a National Magazine Award winner who is now Foreign Policy Magazine’s Senior Diplomatic Reporter, remembers Bishop as a seminal figure in his Berkeley years. “I loved him,” he told me. “I couldn’t write for shit when I first took a class with him, and he was extremely helpful. I was not innately talented as a writer and really had to work hard at it. I was working through stuff I should have worked through in high school, and he was incredibly forgiving of that.”

Bishop could have spent decades toiling on his definitive work on Joyce’s final book. He had to have his edition of the Wake rebound, with one clean page inserted between every page of the book’s text, since his own notes had filled up all available space—and then he filled up each of the insert pages with notes. For years his publisher, Allen Fitchen of the University of Wisconsin Press—best known for publishing Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It when he was at the University of Chicago Press—would prod and encourage him.

Joyce’s Book of the Dark, when it came out, was a triumph. The Wake, Robert M. Adams wrote in The New York Times Book Review in January 1987, is “reputed to be the most forbidding and difficult volume in the world.” Bishop, Adams said, took a fresh approach to unlocking the secrets of the book, and “has ventured on the process more boldly, more thoroughly, more imaginatively and more informedly than any of his predecessors.”

His scholarship will endure. So will the impact he had on countless lives. The Bay Area writer Michael Shapiro, who has been a resident at the small writers retreat center my wife and I run, turns out also to have had Bishop for 125D, the 20thCentury Novel. “It changed my life,” Michael posted on my Facebook page. “My major was political economy but being interested in writing I took a few lit classes and his was terrific. I remember a class when he brought in a Rousseau painting for a writing exercise.”

I hadn’t known anyone could focus as intently as he could, and now that kind of joyous, all-encompassing focus is what I cherish.

I only learned much later that John, who grew up in Auburn, New York, started at Cornell planning to study physics, and one course turned him into an English major. We had that in common. He read Ulysses the summer after college, and earned his PhD at Stanford.

When I did my senior thesis with Bishop, I remember at one point John had the dozen or so students over to his place. What I remember about that was his books, all around us, rising high like the faces of an elevated choir. I could tell this was a worked-over collection, the opposite of Gatsby-library props, but I heard myself blurt out, “Have you read them all?” sounding like a squeaky kid from San Jose, which I guess I was.

John smiled compassionately. I’d embarrassed myself with a stupid question, but my embarrassment was his embarrassment, and he looked down shyly.“At this point,” he began in that soft purr of his. “it’s a matter of two or three times.”

John Bishop taught me something about focus. I hadn’t known anyone could focus as intently as he could, and now that kind of joyous, all-encompassing focus is what I cherish. It’s what I see in Steph Curry playing basketball or my friend Chade-Meng Tan, the former Jolly Good Fellow of Google, talking about meditation.

I came back to campus to see John at one point, towing my niece Katie, and he had as much fun talking to Katie about her hat as to me about my first book. He was merry and charming, happy for me, even if this wasn’t exactly a book to make anyone forget Joyce.

I always wanted to follow up, even after John had a stroke in 2010, but I never did. On Thursday morning, June 11, I googled him, hoping to find a phone number where I could try him. The search autocorrected by adding “obituary” after his name. He’d died of COVID-19 in Syracuse, New York, where he’d been living, on May 15. The discovery knocked the wind out of my lungs. A light was shining inside of me, all these years, illuminated by John. I could feel it dim.

Steve Kettmann, author of One Day at Fenway and Baseball Maverick, is co-director of the Wellstone Center in the Redwoods near Santa Cruz – @SteveKettmann