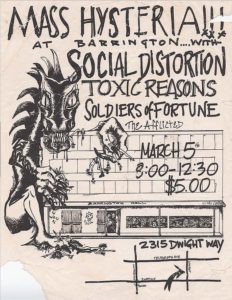

In the Winter of 1979, the residents of Barrington Hall built a stage on the ground floor of their home, opposite the entrance to the dining room. With only about eight feet between the linoleum floor and the concrete ceiling, the stage couldn’t be taller than seven or eight inches. But it was tall enough—upon it, the legendary Berkeley cooperative hosted legions of punk rock and funk metal bands, both famous and forgotten. Everybody played there over the years, from Black Flag to Primus. The name of Primus’s album Tales from the Punchbowl was said to be inspired by the house’s infamous “wine dinners,” at which the punch was reputedly spiked with LSD.

When the Dead Kennedys played at Barrington the following April, it cost just three dollars to get in and the place was mobbed. Sam Quinones, the Barringtonian who booked the performance, remembers that about 350 people crammed into a space that probably shouldn’t have held more than 200. “It was like an oven in there. You just were completely drenched.”

As the crowd piled in, Quinones locked himself arm in arm with his housemates. “We had to form this kind of barricade at the stage with our arms linked, because otherwise the crowd would just go plowing into the band and destroy their equipment.” At the height of the show, Quinones found himself hovering above the ground, lifted by the mass of thrusting bodies. “I got literally pulled by my neck out of my shoes. Like, literally, I saw my shoes there and I was watching my feet being lifted out of them.” Without pausing, he adds, “It was great.”

When it was closed down in 1990, Barrington Hall was the oldest, largest, and most notorious house in the Berkeley Student Cooperative, or BSC, which today puts roofs over the heads of some 1,300 students in 17 houses and 3 apartment complexes. While Barrington’s reputation looms larger than life even now, the co-ops comprise a diversity of settings. They run the gamut from theme houses like Oscar Wilde, one of the first LGBTQ student houses in the nation, and Andres Castro Arms, the newly converted Person of Color theme house, to large houses like the 124-person Casa Zimbabwe, better known as CZ, and the comparatively tiny Kidd Hall that is home to only 17. All are based on a communitarian ethos and are run by the students themselves.

Although the BSC is not formally affiliated with the University, the co-ops are a popular campus housing option—an affordable alternative to dorms, Greek houses, and private apartments. They also tend to attract the free spirits and nonconformists at a university famous for both. Within the co-ops’ wildly painted walls grow all manner of eccentrics and visionaries. Notable alumni include Beverly Cleary, the prolific children’s author who lived in Stebbins; Gordon Moore, co-founder and chairman emeritus of Intel Corporation who lived in Cloyne; and Nancy Skinner, the California state senator who lived in Barrington.

“The place was just a palace of characters,” former resident Adrian Maher ’82 said of Barrington. “I mean one guy would wake up and be crowing like a rooster every morning out the window. We called him our human alarm clock.” On the night he moved in, Maher said a woman stood up at dinner to make an announcement: “I love you all,” she began. “I’m just going to be up on the roof tonight in a sleeping bag, and if anyone wants to come up and make love to me, I would appreciate it.” No behavior was considered unusual, no request too strange. And that was OK with him.

“A lot of people got chewed up by the dope culture and by the slacker culture and ended up wasting themselves and their lives. I don’t want to romanticize that in the least. But it was also a great place to find yourself.”

It wasn’t so hunky-dory with the neighbors, however, who over the years complained of nuisances like noise and litter, but also illegal activity; in particular, alleged drug dealing on the premises. The long-standing palace of characters would eventually be shut down by the BSC amid revelations of widespread heroin use in the house. House members protested the closure, but after 20-year-old Juan Mendoza fell to his death from the roof in 1990, its fate was sealed.

Today Sam Quinones, the erstwhile punk impresario, is a successful author and former reporter with the Los Angeles Times. He looks back with fondness on his time living there, but adds, “I would say this about [Barrington] as well: It could be a catastrophe for you. A lot of people got chewed up by the dope culture and by the slacker culture and ended up wasting themselves and their lives. I don’t want to romanticize that in the least. But it was also a great place to find yourself. And it was very, very cheap.”

Although Barrington’s appeal may have been its power to remove the ground from under your feet, today’s BSC strives to be a little more grounded. Another house, Cloyne Court, was temporarily closed in 2014 after being sued by the family of a student who overdosed and suffered severe brain damage while living there in 2010.

The BSC reopened the house in 2015 under the condition that it take on a substance-free, academic theme. Today, with its well-stocked study rooms and lecture series, Cloyne is a haven for the studious and a welcoming social environment for students who might be recovering from drug dependencies. The co-ops still promote self-exploration, but the BSC’s current focus on affordable and inclusive housing is a far cry from Barrington-style bacchanalia.

Founded in 1933 at the height of the Great Depression, the organization, then known as the University of California Students’ Cooperative Association, aimed to provide low-rent housing to students who wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford college. It also strove to eliminate prejudice and promote tolerance and cooperation through member education.

In some form or another, the organization has held true to these high-minded principles. Rents at the BSC, which became a nonprofit in 1960, are still low—at least, relative to the rest of the Bay Area. At the co-op houses, the room-and-board rate for 2016 is $3,384 per semester, or about $850 a month. By comparison, median rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Berkeley is $2,050. And signing a BSC lease is straightforward, since there are no credit checks or co-signers required. As such, co-ops are a boon to both students seeking affordable housing and to a space-strapped University that is now admitting more students than it has beds for. (Berkeley promotes the cooperative as one of the options for incoming students, but there are already more people on the waiting list than currently live in the entire BSC.)

Part of what keeps the co-ops running is workshift, a shared labor system that keeps the rents low while fostering a sense of community. House members each complete five hours of workshift per week, doing everything from cooking meals to scrubbing toilets to sorting mail. Sure, fraternity pledges have to do similar chores, but in the co-ops the practice is both more extensive and more egalitarian: Everyone’s involved.

“trying to help these co-ops get going, there also developed a free speech problem at the University.… In those days the rules were pretty strict that there couldn’t be any meetings on campus, political or religious.”

As in the Greek system (a comparison most co-opers chafe at), you don’t just live in a cooperative, you join it. And just as the fraternities have their initiations—the hazing rituals of I-Week, commonly known as Hell Week—the co-ops have theirs. Many houses host “disorientation” events at the beginning of every semester, but the initiation rituals do not include hazing and are strictly optional; students can opt out with no social penalty. Consensual involvement and clear communication are central to life in the co-ops. Every semester, residents attend orientations and mandatory workshops that lay out the cooperative rules and introduce concepts such as power, privilege, and marginalization—ideas that are meant to inform residents’ behavior. And it’s not just empty rhetoric. Students in the co-ops tend to be activists—in the ’80s, residents of Barrington rallied for Reagan’s impeachment and against Apartheid, and today co-opers take to the streets in support of Black Lives Matter, the Women’s March on Washington, and other movements.

One look at the walls of Lothlórien, the vegetarian house nestled on Prospect Street, and it’s clear that political passion is alive and well. “Down with capitalism, Down with Trump” reads one poster tacked to the front door. Others nearby call for Campesino Power and denounce Killer Cops. Alfred Twu has roomed and/or boarded at the co-ops, including Loth, since 2003. He says, “Loth is the Berkeley your relatives warned you about. We kind of check off every single Berkeley stereotype, and we celebrate that.”

The progressivism isn’t exactly new, but it grew from an unlikely source. Before he died in 1982, Harry Kingman, the Christian missionary who helped found the BSC, remembered that, when he was “trying to help these co-ops get going, there also developed a free speech problem at the University.… In those days the rules were pretty strict that there couldn’t be any meetings on campus, political or religious.”

Stiles Hall, which Kingman ran, was a community service center, and at its founding Kingman worked to implement a free-speech policy, to create a space that was unrestricted by the censorship on campus. The co-ops grew out of this model. “The key thing right from the beginning is that this particular University Student Cooperative Association has been student run, student-controlled,” Kingman said.

That Berkeley’s co-ops are still student run is a powerful component of living in them. Just as you are in charge of cooking for your housemates (at Barrington, a resident once cooked a dinner entirely of insects and started a house tradition), you are also empowered to take control of your life—something only rarely gleaned from a college classroom.

Sam Quinones learned how to throw a concert in his Barrington days, but it was the DIY spirit he took with him into his writing career. “I don’t see too much of a difference between what I was doing at Barrington and a lot of the freelance things that I’ve been doing,” Quinones says. “It was all part of a piece, part of the same idea, that you should try to design your own life and not let someone else do it for you.”

The houses, like their members, are highly autonomous. But they are also overseen by a central office, better known to the house members as Central, or CO. Zach Gamlieli is the BSC’s external affairs vice president and a resident of Casa Zimbabwe. He compares Central, which employs full-time professional staff members to oversee everything from the centralized food warehouse to bookkeeping and alumni relations, to the federal government. The individual houses, he says, are like the states. Houses are encouraged to fill in the blanks of Central-level policy (the bylaws of Oscar Wilde House, for example, take care to mention that “no bodily fluids may be released into the hot tub”), but the relationship between the BSC and its properties is still fairly structured. All house-level managers, for example, have a direct supervisor at the central level, and all houses are required to run workshops on harm reduction, emergency preparedness, and other salient topics—including sexual consent, for which the BSC’s training materials are so thorough that they are being adapted for use by Greeks Against Sexual Assault.

Gamlieli thinks the republic is functioning well at the moment. “We’re being called out, sometimes even to our own surprise, as really great neighbors and really great housing providers.” It wasn’t always so. At the time of Barrington’s closure, the BSC was, in the words of Twu, “comically hands-off.” He remembers “somebody was complaining about their housemate growing weed, and CO told them to take care of it at the house level.” Joel Rane, who lived in Barrington in the wild years of 1984–87, concurs. CO saw the house as a problem, Rane says, but didn’t do anything about it. “We were all kids,” Rane says. “We needed some kind of guidance.”

With so many houses serving so many students, it makes sense that, for most co-opers (a label that applies to both authors of this article), allegiance is felt primarily to one’s residence and secondarily to the BSC as a whole, no matter its policies. The relationship between individual units and Central has at times become outright antagonistic, as in the lead-up to Barrington’s closure. Another more recent example occurred in 2005, when lawsuits by irritated neighbors forced the conversion of illustrious house Le Chateau (former home to Berkeley’s most celebrated nudist, Andrew Martinez, aka The Naked Guy) into Hillegass-Parker House, a quiet graduate student cooperative.

And therein lies an almost inescapable tension between youthful freedom and adult control. The dynamic isn’t unique to the co-ops. In loco parentis, a Latin term meaning “in the place of a parent,” refers to the responsibility that institutions such as schools have toward their charges. Historically, in loco parentis was used to justify paternalistic policies in higher education. As late as the early 1960s, for example, women attending Berkeley found themselves locked out of the dorms if they stayed out past curfew, and students could face academic penalties for “conduct unbecoming a student.”

The Free Speech Movement at Berkeley was partly a reaction against in loco parentis, and although this framework has largely disappeared from higher education, it is still a useful way to understand the unique responsibilities that the BSC, a landlord in name but a steward in spirit, owes its members. It can also help explain some of the tensions that arise when these members bristle at the policies of their parent organization.

Most would agree that the ideal relationship is a negotiated settlement between Dionysian excesses and an Apollonian insistence on order—that is, broad freedoms within well-reasoned limits. In the wake of changes to the BSC’s top leadership, most observers agree that balance has been restored somewhat.

Kim Benson, the BSC’s executive director and an alumna of Casa Zimbabwe and Euclid Hall, describes the relationship between the houses and the Central level as one of constant communication and mutual accountability. It is a relationship she is hoping more members become involved in. “One of our strategic priorities is to create systems to increase member participation in governance, policy, and decision making,” she says. This way, “each individual member is able to suggest improvements, take advantage of leadership opportunities, and help us continue to improve the services we offer and the community we co-create.”

These days, another key priority for the organization is bringing membership demographics in line with the BSC’s mission statement by increasing racial and economic diversity. According to Zach Gamlieli, targeted recruitment efforts are ongoing. But progress has already been made, especially in the houses, which have historically skewed white and upper-middle class. (The apartments, which offer cheaper rent but no meals, have long been more diverse.)

“We are getting better and better at meeting our mission,” says BSC president Kevin Ramirez, himself a low-income, first-generation college student. The numbers back him up. Last fall, 56 percent of total co-op membership was made up of students who are part of the Educational Opportunity Plan, which serves low-income, first-generation, and historically underrepresented students. Eight years ago, that number was only 27 percent.

Day to day, Central also works in tandem with the houses to oversee such things as house habitability and safety conditions. As underscored by last December’s tragic Ghost Ship warehouse fire in Oakland, neglecting such concerns can spell disaster. In spirit, the Ghost Ship collective (an ad hoc group of artists living in a warehouse space in Oakland’s Fruitvale District) resembled the co-ops. It was cheap, communal, and experimental, a refuge for artists in a city where artists struggle to pay rent. As it turned out, the building also had poor wiring, no sprinklers, and no clearly marked emergency exits to protect residents and guests in an emergency. When a fire broke out during an event on the night of December 2, 36 people, including 4 from the Berkeley community, were killed (see In Memoriam pg. CAL7).

At the co-ops, the BSC provides safeguards against such catastrophe. When a house wants to throw a party, it is required to register with the fire department for an indoor event clearance ten days in advance, and a fire inspector comes ahead of time to make sure the building is safe. Houses also tape a poster by the entrance, stating the event’s clearance guidelines, which include bullet points such as “Smoke outdoors only” and “Do NOT exceed occupancy limit.” Ultimately, of course, it’s the students’ responsibility to abide by these rules, but it makes all the difference to be given the resources to follow them. According to Gamlieli, the BSC today provides “an incredibly safe space for people to learn, grow up, and find themselves.”

They find others as well. Twu says that living in the co-ops “gives people access to resources and connections they would have no other way to tap into.” Years after graduating from Berkeley, Maher found himself at Pelican Bay, the state’s maximum security prison, hoping to interview solitary confinement inmates for a television series he was producing. “I couldn’t get in, couldn’t get in, and then I was finally talking to the warden—and it turned out he lived in Barrington. It was just like a code word,” Maher said, “and the next thing you know I got the warden of Pelican Bay agreeing to let me interview the solitary confinement inmates.”

Barrington may have closed, but the connections formed there persist. While the concrete edifice still stands, the building has been converted into privately owned student housing—a far cry from the “palace of characters” it once was. Given this erasure, a song by Primus lead man Les Claypool poses a poignant question: “Does anybody here remember Barrington Hall? Does anybody here remember Barrington?”

The resounding answer is yes. More than eight decades have passed since the co-ops were founded. Since then, thousands of students have passed their college years absorbed in the rhythms of co-op life. And while the character of that experience may change from house to house and semester to semester, something essential remains consistent—a nonconformist, community-minded value system that outlives the individual. Houses and students may come and go, but the spirit is passed forward into the future.

You could call it the soul of the place.

Sarah E. Adler ’16 lived in Oscar Wilde and majored in media studies. Alastair Boone ’16 lived in the new, studious Cloyne and majored in English. Both are California interns and native Californians.