PATTY HEARST STARED OUT THE WINDOW at the corn rows flying past, bored to death by the man next to her who talked nonstop about sports and revolution—two things she was pretty sure had nothing to do with each other. The man’s name was Jack Scott. He was 32, balding, with a runner’s build and alert blue eyes that Patty would later describe as shifty.

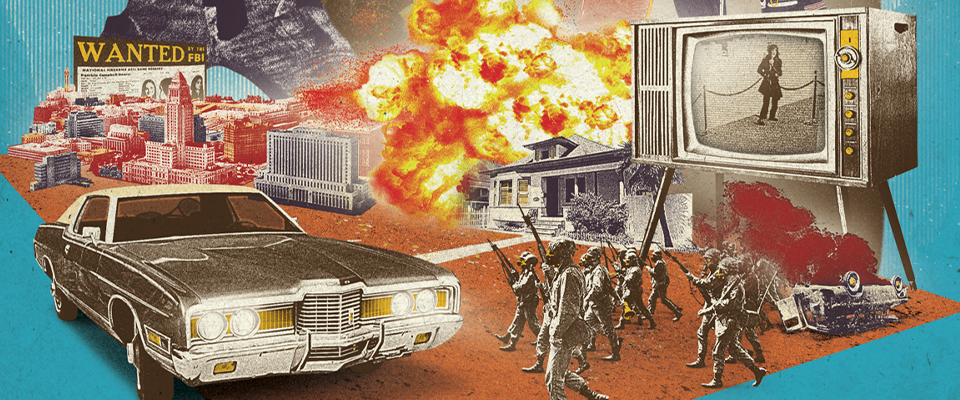

It was late June 1974—the year Hank Aaron broke the Babe’s home run record, the year Nixon decamped the White House in disgrace, the year Hearst, a 19-year-old Cal sophomore and heiress to her grandfather’s publishing fortune, had been violently snatched from her Berkeley apartment by a small, cultish group calling itself the Symbionese Liberation Army.

In a tape-recorded communiqué, she reintroduced herself to America via her new nom de guerre. “Greetings to the People. This is Tania.”

The SLA had vowed to wage “revolutionary war against the fascist, capitalist class” by “force of arms and with every drop of our blood,” but its first public act had been the senseless killing of a popular black educator: Dr. Marcus Foster, superintendent of Oakland public schools. They shot him with cyanide-tipped bullets. In kidnapping Hearst and leveraging her to demand a massive food giveaway to the poor, the SLA had managed to recast themselves as a band of Robin Hoods while thrusting the Hearst family into the headlines of its own newspapers.

As if the bizarre story didn’t already have enough tabloid elements, Patty Hearst, two months into her captivity, joined her captors’ cause, appearing on security camera during a bank robbery holding an M-1 rifle and barking orders at terrified patrons. In a tape-recorded communiqué, she reintroduced herself to America via her new nom de guerre. “Greetings to the People. This is Tania.”

Whether it was the voice of Stockholm syndrome or Patty herself expressing genuine revolutionary conviction is a question that, nearly a half-century later, remains unanswered. And yet, as intriguing as that question is, it obscures others. For starters, why did anyone support the SLA? How did Patty Hearst remain on the loose for so long? And how did someone like Jack Scott, a former college athletic director with a 1972 Ph.D. in education from UC Berkeley, come to be sitting next to the most wanted fugitive in America as they rode across the country in the back seat of a Ford LTD?

Was there some method to this madness or had the radical left simply lost its mind?

BORN IN 1942 IN SCRANTON, PENNSYLVANIA, Jack Scott grew up in a chaotic home. His mother was a nervous wreck. His father’s alcoholism bankrupted the family business. A mercurial older brother named Walter would join the Marines, then claim to work as a government gun for hire in trouble spots like Libya and Cambodia.

Standing on his doorstep, Scott raised his right fist. “The FBI might be in power now, but you won’t be in power for long. Power to the people.”

For his part, Jack was a tough, energetic kid, who found refuge and his identity on the football fields and oval tracks of his hometown. In high school, he captained the city-champion football squad. Teammates called him “Chief.” In college, he bounced around, with brief stints at Villanova and Stanford, where a bum foot apparently hobbled his running career, finally finishing at Syracuse, where he continued to run but to little acclaim. He did, however, excel as a student, graduating magna cum laude in 1966 with a degree in psychology.

It was during the Stanford interlude that he met the love of his life—an attractive, well-to-do young woman named Beverly McGee, known to everyone as Micki. The couple came to Berkeley in 1966 so that Jack could attend graduate school. He said later that he arrived a Goldwater Republican but became radicalized at a Stop the Draft protest in Oakland where he and Micki helped bandage kids bludgeoned by the cops, using their VW bus as a makeshift ambulance.

Two years later in 1969, the FBI would investigate Scott under anti-riot statutes in connection with a pamphlet called “Your Manual,” a kind of precursor to The Anarchist Cookbook, complete with instructions for making pipe bombs and Molotov cocktails and advice on how to fight cops at protests. Sample tip: Throw red pepper downwind at police horses. “If you hit your target, the pig may end up on his ass where he belongs.”

When agents knocked on Scott’s door in North Oakland, he greeted them with a tape recorder slung over his shoulder. They demanded he stop recording, but Scott stood his ground, suggesting they continue the interview at the offices of Ramparts, the radical magazine where he was then sports editor. Ultimately, the agents retreated. Standing on his doorstep, Scott raised his right fist. “The FBI might be in power now, but you won’t be in power for long. Power to the people.”

THE WHOLE WAY ACROSS THE COUNTRY, they stayed in the slow lane. Patty slumped in the back seat in a wig and glasses.

Jack’s father, by now many years sober, drove. His mother rode shotgun. Both were in their 60s. The mother was nearly as talkative as Jack, and she boasted to Patty, who insisted on being called Tania, about how her own mother had helped hide IRA soldiers back in the old country.

The jock liberationists saw it differently. Sports, they argued, were merely a reflection of the larger society, prone to the same bigotry, biases, and blind spots.

Scott had recruited his folks for the job because he knew they were unlikely to attract attention, especially driving a “conservative car” with Ohio plates. To make extra sure, he displayed a couple of tennis rackets in the rear window and bought Patty jogging gear. The perfect disguise, he insisted. Who would ever suspect athletes of being revolutionaries?

Who indeed? And yet here was Jack Scott, the very exemplar of a new breed: the sports radical. And a prominent one at that, already hailed by Time as “the Jeremiah of Jock Liberation” and denounced by Vice President Spiro Agnew, who called him a “permacritic” and “a guru from Berkeley.”

Scott had coined the term “The Athletic Revolution” in 1971, when he published a book by the same title. The epigraph was a quote from IRA activist, Bernadette Devlin: “We were born into an unjust system; we are not prepared to grow old in it.” In the book, he called for big-time athletics to be wrested from the authoritarian control of coaches and athletic directors and returned to the players themselves.

“Athletics for Athletes” was Scott’s rallying cry—and the title of Scott’s monograph, which featured a provocative chapter in which he deconstructed the culture war then raging between coaches and players over hair length. “No one loathes homosexuals quite as much as a latent homosexual,” Scott wrote, “and long hair on a male, since it has in recent times been associated with femininity, will arouse the anger of a latent homosexual like almost nothing else in the world can.”

In Berkeley, Scott founded an organization he called the Institute for the Study of Sport and Society and ran it out of his home. The operation may have been little more than a telephone and a filing cabinet, but Scott’s board was a veritable who’s who of leading figures in the movement, including: Newsday sports reporter Sandy Padwe; St. Louis Cardinals linebacker Dave Meggyesy who had published, with Scott’s help, a broadside against the NFL called Out of Their League; and Harry Edwards, the 6′ 8″, 275-pound sociologist who had authored the seminal 1969 book, The Revolt of the Black Athlete.

By the time Patty Hearst was kidnapped, it must have seemed to many Americans—left and right, young and old—that the country was coming apart at the seams.

Their views were not necessarily monolithic. Edwards, for one, said he and Scott came at the “revolution” from markedly different perspectives. “Jack Scott was talking about who controls the athletic enterprise, you know, that it was a top-down dictatorship by people controlling the means of production,” Edwards said. “That was all well and good, but you know what? I had enough trouble being black. I didn’t have time to get involved with a bunch of stuff having to do with reds.”

Of course, to most people in the counterculture, the sports world was largely beside the point: hopelessly bourgeois, counterrevolutionary, more opium for the masses. The jock liberationists saw it differently. Sports, they argued, were merely a reflection of the larger society, prone to the same bigotry, biases, and blind spots.

AT RALLIES HE’D ORGANIZED AND PARTICIPATED IN at Berkeley, Scott had witnessed firsthand how athletic intensity could be channeled into radical zeal. In the lead-up to the 1970 Cal-Stanford game, his friend Sam Goldberg, a top decathlete and Olympic hopeful from Kansas, told a crowd, “You will see athletes melt down their medals and trophies to make bullets for the revolution.” And: “Any athlete who is serious about liberation and revolution must be prepared to kill his coach.” At the Big Game itself Goldberg wrapped himself in a Viet Cong flag and stormed the field at halftime, only to receive a drubbing from the Stanford marching band.

No doubt the spectacle struck the grown-ups in the stadium that day as madness, more evidence their beloved Cal had gone berserk. In the minds of many youth, however, it was the adult world that had gone insane. My Lai, Kent State, Attica, Watergate…. By the time Patty Hearst was kidnapped, it must have seemed to many Americans—left and right, young and old—that the country was coming apart at the seams.

In response—and nowhere more so than Berkeley—the ranks of the militant left swelled with disillusioned youth, many of whom decided that armed resistance was the only answer.

Other unseemly details gleaned from Scott’s voluminous FBI file, draw a portrait of the man as petty, volatile, and emotionally unstable.

Athletes were not immune to the revolutionary undercurrent. And if anything is more dangerous than an embittered idealist, it’s an embittered idealist with brawn, cunning, and a determination to win.

Robert Lipsyte saw all that in Jack Scott, and more. The New York Times reporter first wrote about him in the winter of 1970 when Scott, still a graduate assistant, was teaching a course at Cal called Intercollegiate Athletics and Education: A Socio-Psychological Evaluation. In his article, Lipsyte painted the scene for readers: Scott striding into the jam-packed auditorium of 400 students, dressed like a coach and blowing a whistle to start class.

He told Lipsyte afterward, “When I walked in and blew that whistle, the class looked startled. A teacher blowing a whistle in class—that’s incredible. Yet 300 yards from here, men who are supposed to be teachers act and dress like this all the time, curse their students and impose arbitrary rules about hair, clothes, social life, and no one thinks twice about it. I hope this course makes people think twice—then do something to make the university approach to athletics more holistic instead of a fetish for performance statistics, and stop those coaches who are distorting one of the most creative and exciting activities of college life.”

Scott seemed to have it out for coaches—most of them, anyway. At Stanford, he’d locked horns with track coach Payton Jordan, who later told FBI agents that Scott labeled him in his writing as “queer and racist.” When Jordan was selected to coach the 1968 Olympic squad, Scott allegedly made harassing calls to his home in Palo Alto, only stopping after the coach threatened to call police. At Syracuse things were no better. He allegedly spat at one of his coaches while the man was with his family and, on another occasion, tried to kick in his front door.

In public statements, Jack always maintained that he opposed political violence as counter-productive and immoral. How truly he believed that is unclear.

These and other unseemly details gleaned from Scott’s voluminous FBI file, draw a portrait of the man as petty, volatile, and emotionally unstable. But a much different picture emerges from friends and acquaintances who say Scott was thoughtful, principled, and soft-spoken.

Even strangers were often struck by his cool demeanor. Famed sports reporter Dick Schaap, expecting a firebrand, asked Scott during an interview, “Are you always so rational or is this an unusual day?”

But friends also admit he was complicated. In his 2011 memoir, An Accidental Sportswriter, Lipsyte wrote, “There was always an undercurrent of hustling with Jack, even if it was for the right causes.”

In an interview after his book came out, Lipsyte acknowledged that Jack was an operator. “Sure he was. But he had an idea. And obviously, it was at least an interesting idea or we wouldn’t be talking about him.” But, he added, “find anybody who accomplished anything or raised other people’s consciousness: They were charismatic. They had moves. They knew how to attract media.”

IN PUBLIC STATEMENTS, JACK ALWAYS MAINTAINED that he opposed political violence as counterproductive and immoral. How truly he believed that is unclear.

In the preface to “Your Manual,” the pamphlet the FBI had tried to question Scott about in 1969, the author mocks the peaceniks, stressing that, “The oppresors [sic] cancerous hands are around our throats and they will only release them when he sees his own blood on the earth.”

Scott sprang into action, helping Brandt’s girlfriend, which earned him a reputation around Berkeley as a kind of Harriet Tubman of the militant left and later helped gain him an audience with the SLA.

Did Scott write “Your Manual”? Payton Jordan thought so, and not without reason. At the end of the document, in the “coming soon” section, the following curious item appears: “The queer jocks and how to get them by Payton Jordan (Stanford U. white cracker racist dog track coach.)”

Writing in Esquire magazine in 1975, Roger Kahn said of Scott that he had “done no violence except on football fields” and then only at the behest of coaches. Yet, while there’s no evidence that Scott personally engaged in violence, he was quick to lend support to those who did.

One of Scott’s closest friends in Berkeley was Cal dropout Willie Brandt, allegedly one of Berkeley’s most prolific bombers, suspected of having a role in at least nine Bay Area bombings, with targets ranging from local bank branches to Berkeley campus buildings. No one was hurt in these bombings, which usually went off in the dead of night. They were meant to make a statement.

Brandt was apparently planning to bomb the Navy ROTC building next when he was arrested on the morning of March 31, 1972, along with two would-be accomplices, both acquaintances of Scott’s—Michael Bortin (who would later join the SLA) and Paul Rubenstein. The trio was apprehended in a Berkeley garage packed with weapons and explosives.

Upon hearing news of the bust, Scott sprang into action, helping Brandt’s girlfriend, Wendy Yoshimura, who had rented the garage under an alias, go underground—first driving her to LA, then flying her to the East Coast where she assumed a new identity. It was this adventure that earned him a reputation around Berkeley as a kind of Harriet Tubman of the militant left and later helped gain him an audience with the SLA.

THE SAME YEAR BRANDT WAS ARRESTED, Scott was hired as athletic director at Oberlin College by 34-year-old President Robert Fuller, then the youngest college president in the country. Fuller had read The Athletic Revolution and asked Scott’s advice on whom to bring on as AD. Scott recommended himself.

Once installed, he swiftly instituted reforms that, today, would barely raise eyebrows, but at the time were considered remarkable. They included doing away with entrance fees to athletic events, placing greater emphasis on women’s sports, and hiring a number of black head coaches at the predominantly white school. Among those brought on by Scott was sprinter Tommie Smith, of the black-gloved Olympic protest movement in Mexico City. His coaches even recruited a couple of ringers for the football team, including a Hispanic quarterback, who helped lead Oberlin to its first winning season in years.

He watched on television on May 17, 1974 as the core of the SLA burned to death in a fiery shootout with the LAPD in Watts. Six bodies were identified in the ashes.

When legendary broadcaster Howard Cosell visited the famously liberal Ohio campus for ABC Sports and reported on Scott’s experiment there, he was duly impressed. In his trademark staccato, Cosell gave the program a benediction of sorts: “I don’t know if it’s going to work, but I don’t know why it shouldn’t, because the essence of this program is lodged in the basics of the American democracy, the Constitution, and what this country is supposed to be all about.”

In fact, it didn’t work. A year and a half into his four-year contract, Scott was forced to resign amid a campus revolt. A list of complaints against his department, signed by more than 200 athletes and physical education students, was published in the school paper. It seemed that for all Scott’s democratic ideas (he gave players veto power over the hiring of coaches, for example), he could be dictatorial in implementing them, often threatening to “get” anyone who stood in his way.

Dan Millman, a former Cal gymnast and world trampoline champion, whom Scott recruited to coach at Oberlin would later tell the FBI that Jack was brutal in his treatment of “older establishment types” and would often become so angry that he would clench his fists and tremble with rage. In one case, he allegedly assaulted a teenager. Even Fuller, who championed his hiring, admitted to agents that Scott was difficult, possibly even dangerous. He and Millman both mentioned concerns that the AD might bomb the new gym on his way out the door.

In the end, the college decided it would be safest to buy him out and Scott was paid the remainder of his contract: $42,000 (a little more than $220,000 in today’s dollars).

Scott was unrepentant. In a farewell interview, he told one local paper, “I’d much rather be leaving, with the circumstances being as they are, than having left and people say, ‘Wow, he certainly was a wonderful guy, but he never did anything he said he’d do.’” In another interview, he referenced his favorite musician. “As Country Joe McDonald sings, ‘Entertainment is my business’ and I’m glad I’ve brought a little excitement into your lives.”

FROM OBERLIN, JACK AND MICKI SCOTT moved to New York’s Upper West Side where they reopened their sports institute and Jack, depressed after his ouster, nosed around on a book project dealing with performance-enhancing drugs including steroids and uppers, which he accused team trainers of handing out like candy. For the summer, the Scotts planned to rent a farmhouse near the Poconos, someplace secluded where Jack could write. The book project failed to inspire, however, and his attention soon latched on to something bigger.

Amped on adrenaline, Jack made his pitch, told them he wanted to tell their story, explain the SLA to the world.

Like much of the country, he watched on television on May 17, 1974, as the core of the SLA burned to death in a fiery shootout with the LAPD in Watts. Six bodies were identified in the ashes. Only Patty Hearst and two others had survived. Unbeknownst to the cops, they weren’t in the hideout with the others but rather in a motel near Disneyland, watching the spectacle on live TV. If Patty had wondered whether the authorities would hesitate to kill her, she now had her answer.

Scott was at once transfixed and horrified. Though the SLA had refused to surrender, firing thousands of rounds at police, Jack saw it as summary execution—“murder by law enforcement.” While he seethed at the perceived injustice, he also saw an opportunity. There was a big story, one that would garner a huge advance and even greater acclaim. And given his ties in Berkeley’s underground circles, Scott felt he was uniquely placed to get it. He flew back to the Bay Area and started making calls.

It was his friends, Kathy Soliah and her boyfriend James Kilgore, a former college volleyball player, who took him, blindfolded, to an apartment on Berkeley’s Northside. When the blindfold came off, there sat Patty Hearst and her two captors-cum-comrades, Bill and Emily Harris. All three were armed to the teeth, holding rifles and decked out in ammo belts and bandoliers.

Amped on adrenaline, Jack made his pitch, told them he wanted to tell their story, explain the SLA to the world. In exchange, he would take them across the country to the farmhouse he was renting. They could stay there, far from the West Coast dragnet and enjoy some fresh air. His book project would be perfect cover. If anyone asked, they could pretend to be his research assistants. Flush from the Oberlin buyout, he promised to cover all expenses.

The only condition: They would have to disarm—something they agreed to do reluctantly and only with the understanding that Scott would get them weapons when they reached their East Coast hideout.

The fugitives would travel separately. Scott’s friend and fellow Cal Ph.D., Phil Shinnick, a world record holder in the long jump, agreed to shuttle Emily Harris in his Pinto. Scott and his parents would take Patty.

Scott couldn’t write—not very well, at least. If he was going to turn the SLA story into a bestselling book, he needed to find storytellers.

In Scott’s version of the story, his father pulled over on San Pablo Avenue before getting on the highway and leaned over the backseat to address Tania.

“We can take you wherever you want to go,” he said.

Her answer, reportedly: “Take me where-the-fuck you’re supposed to or you’ll be dead, not just me.”

Hearst later denied the exchange ever happened.

AT THE FARMHOUSE, SCOTT BROUGHT IN Wendy Yoshimura, whom he tracked down in New Jersey, to “babysit” the fugitives and run errands. He gave her a VW bug and $600. Later, he brought in Paul Hoch, a Canadian scholar and author of Rip Off the Big Game—another book Scott helped usher into publication—to conduct taped interviews with Hearst and the Harrises.

Plans for the book were coming together. The only problem was Scott couldn’t write—not very well, at least. His prose tended toward the pedantic and self-involved, his books featuring long excerpts of other people’s writing and speeches. If he was going to turn the SLA story into a bestselling book, he needed to find storytellers.

It was Michael Kennedy, Scott’s radical attorney, who introduced him to reporters David Weir and Howard Kohn, both of whom had backgrounds in the underground press and were now working for Rolling Stone. While the fugitives spent their time back on the farm dictating, skinny-dipping, and taking target practice in the barn with BB guns—the only weapons Scott provided his guests—Scott and Micki spent most of their time at their apartment in New York or in San Francisco, where Jack gave interviews to Weir and Kohn.

“It is apparent that Scott knows more about this case, first-hand, than anyone else. His book, if he ever writes it, will make him a million.” —Herb Caen

On the farm, meanwhile, Hearst and the Harrises grew restive and paranoid, anxious to get back to familiar ground. As the summer wore on, the Scotts too, grew tired of the stressful arrangement. They had a new supporter in Portland Trail Blazers basketball star Bill Walton, who shared Jack’s politics and taste in music. Walton and the Scotts were so simpatico, in fact, that he invited the couple to live with him in his Oregon home. Before they could enjoy their new friend’s largesse, however, they needed to shed their burden back East.

This time, Scott took responsibility for Hearst’s transport only. He agreed to drive Patty, in a rented van, as far as Las Vegas. On the way, they were stopped by police, and Scott again used sports as a diversion, palavering with the cop about football. (How about that Iowa game, officer?) They were sent on their way.

The day after arriving in Vegas, Scott left Hearst at a motel on the Strip, where she was met by James Kilgore, now a member of the SLA. The two traveled to Sacramento by Greyhound, Hearst wearing a wig and a pillow under her dress. Scott would not see her again.

It would be nearly a year before she was arrested, along with Yoshimura, in a San Francisco safe house. In the interim, the SLA had recruited new members and resumed bombing police stations and robbing banks. In one of those “actions”—a bank heist in Sacramento—Emily Harris shot a woman who bled to death on the bank floor as they made their getaway.

Mysteriously, Scott was never charged with a crime and never went to jail. He never produced his book about the SLA either.

When, shortly after Hearst’s arrest, Rolling Stone published its inside story of the SLA’s “Lost Year,” it was obvious to many in the Bay Area who had been the main source for the story. Even the San Francisco Chronicle’s famed gossip columnist Herb Caen knew it. “It is apparent that Scott knows more about this case, first-hand, than anyone else,” Caen wrote in the paper. “His book, if he ever writes it, will make him a million.”

It wasn’t a revelation that would win Scott any friends in the underground. To cover himself, he accused his attorney Michael Kennedy of betraying him. David Weir and Howard Kohn, he insisted, had been introduced to him as Kennedy’s legal researchers, not reporters—a charge both journalists have always strenuously denied. The evidence would seem to back them up. Contained in Scott’s FBI files is a Western Union telegram he received a month before the story broke. “We’ve written 46 pages. Like you to read it before returning East.”

It was signed “David and Howard.”

PATTY HEARST’S TRIAL WOULD SPAN SEVERAL WEEKS and spawn countless more headlines before she largely disappeared from public consciousness. In the end, she was sentenced to seven years in prison and served less than two years before President Jimmy Carter commuted her sentence.

Mysteriously, Scott was never charged with a crime and never went to jail. He never produced his book about the SLA either. The closest he came was a 1978 book, ostensibly about Bill Walton (called Bill Walton), in which he spent several pages recounting how federal investigators hounded him and his family despite their innocence. “If our actions somehow avoided further bloodshed and killing, we find that nothing to be ashamed of,” Scott wrote, and even went so far as to suggest that whoever had hid Patty Hearst and the Harrises had saved police from a revenge sneak attack, one that “probably would have claimed the lives of many law enforcement officials.”

JACK SCOTT DIED IN 2000 AT AGE 57 of throat cancer, his years at the vanguard of the revolution long over. He had stayed involved in sports though, as a physiotherapist treating world-class runners with a technique that used electrical stimulation to heal injuries. Among those he administered to were track superstars Carl Lewis and Jackie Joyner-Kersee. According to Robert Fuller, the former Oberlin president who later moved to Berkeley and remained friends with his old AD, Jack got rich.

Scott himself would say that the SLA was a symbol of his “generation gone crazy.”

Before his death, when it was obvious Scott was quite ill, Fuller suggested a reunion of the old gang in Berkeley to “celebrate everything we had accomplished at Oberlin.” Olympic sprinter and Black Power activist Lee Evans came. So did George Sauer, who had quit the New York Jets in 1970 to join the counterculture. And Tommie Smith. Scott sent a stretch limo to pick him up from the airport. When the ringers from the old football team showed up, Scott gave them Rolexes.

Years later in 2011, Fuller said Scott’s involvement in the SLA saga was a “sleeping dog” he’d prefer to let lie. “I don’t give a damn about any of it.” He felt Scott deserved to be remembered for his accomplishments even as he acknowledged his friend’s complexity. Scott, he said, was a sort of “borderline personality” who “could operate within the establishment and hold the establishment up to its own best ideals. At the same time, he could step on over into being a pirate, being a wild man.”

Scott himself would say that the SLA was a symbol of his “generation gone crazy.” Perhaps the same could be said of him.

Pat Joseph is editor in chief of California.

From the Spring 2020 issue of California.