Once on staff at the Daily Cal, Bell is now a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Darrin Bell was about 5 years old when he discovered political cartoons. He was living in Southern California, and he came across the work of Paul Conrad while leafing through issues of the Los Angeles Times.

“I was just a little kid, but I learned about the Iran hostage crisis through Conrad,” Bell recalls. “I loved his images, and I asked my parents what they meant. They explained them to me, and I followed them avidly. I knew I wanted to do that kind of work someday.”

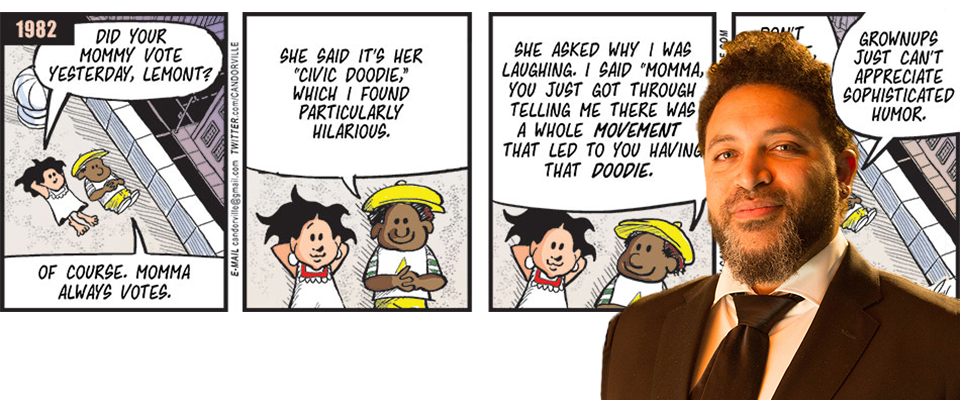

And ultimately, he did. Bell’s mother was a talented artist, and she schooled him rigorously in technique. When he enrolled at UC Berkeley in 1993, he was a highly accomplished caricaturist and was quickly appointed as editorial cartoonist for the Daily Californian. He also sold cartoons to the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Oakland Tribune while still a student, and produced a comic strip, Rudy Park, in collaboration with journalist and fellow Cal alum Matt Richtel [aka Theron Heir]. He kept drawing after taking a BA in political science in 1997, producing editorial cartoons, Rudy Park and a second strip, Candorville, a humorous and bittersweet narrative on the lives of young inner city African Americans and Latinos; both Bell’s strips and his editorial work are now syndicated.

Last month, Bell was awarded the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for editorial cartooning—the first African American to receive the award. The judges declared the prize was bestowed “…for beautiful and daring editorial cartoons that took on issues affecting disenfranchised communities, calling out lies, hypocrisy and fraud in the political turmoil surrounding the Trump administration.”

Bell recently skirted a deadline or two to talk to California about his career and life.

Congratulations on winning the Pulitzer. Your life is extremely busy these days, with the production of both editorial cartoons and two daily comic strips. Which is more difficult—the editorial work or the strips?

I’d have to say the editorial cartoons. It’s almost performance art—something breaks on the news, and you only have a few hours to respond, to make deadline. I also tend to work up to the deadline with the strips, but there’s not as much real pressure. I have ideas bouncing around in my head for a week or so, and they gradually crystallize. Then I typically sit down and draw an entire week’s worth of strips in one day.

The ability to caricature prominent people is a foundational talent for political cartooning. How do you approach that with someone like Trump, who seems like almost excessively fertile ground for caricature?

I usually start out with a lot of detail and then simplify. You want to emphasize their physical characteristics rather than how they make you feel, but that can be difficult to maintain. I used to draw Trump with his eyes open. After a while I decided that one of his primary characteristics is that he doesn’t listen to or even see anyone other than himself, so now I draw him squinting or with his eyes closed. I’m also starting to draw him smirking more and more, like The Joker in Batman, because he’s starting to feel like The Joker to me—not a person so much, but a manifestation of everything that’s wrong in Gotham.

What’s the bedrock ethos of editorial cartooning?

An editorial cartoon is not a gag. Bob Mankoff [former cartoon editor for The New Yorker] called me a few years ago out of the blue and asked me to submit cartoons to the magazine. And I pointed out that I’d never done gag work. And he said editorial cartoons were basically gag cartoons—both have a single image and a caption. But they’re not the same thing. For me, editorial cartoons don’t have to be funny. I want them to make people think and feel, even if they end up thinking I’m an idiot and want horrible things to happen to me.

In Candorville, one of the main characters is a young writer who regularly submits his work to The New Yorker and is rejected. Did you ever submit any of your cartoons per Mankoff’s request?

I did, and one was accepted after eight or nine attempts. And it just ran, as a matter of fact. They held it for a year or so, and then finally published it. I’d been checking each issue every week to see if it had run and then basically given up. But apparently, that’s standard practice—they can hold cartoons for a long time.

You’ve cited Paul Conrad as an influence, noting that he both infused you with a love of cartooning and helped you understand the world as a very young child. Could you expand on that?

I began reading Conrad at 5, but I was drawing at 3, scribbling on the walls at home. They were mainly cartoons about my life with my brother, how horrible he was because he wouldn’t let me read his comic books. At that point, my mother—who’s a great artist—sat me down with some paper and taught me everything she knew. Given that I admired Conrad so much, I studied his technique closely, and I thought he used charcoal, so I asked my mother to buy some. Then I just spent hours and hours copying Conrad’s cartoons, trying to duplicate his images. At a certain point I realized that my work didn’t look like Conrad’s work—but it looked good, and I was actually developing my own style. And now, when young and aspiring cartoonists ask for advice, what I tell them surprises them, strikes them as counterintuitive, because I say they should find someone whose work they admire and then copy the hell out of it. They’re unlikely to reproduce the images exactly, but they’ll develop their own techniques.

Both your comic strips and your editorial work deal unflinchingly with race and ethnicity. Have your own experiences informed these themes?

What my grandfather faced was so much worse than what I dealt with, but yes. For me, much of the discrimination I felt related to my work. I was told by editors that they liked Candorville, but they didn’t think people could “relate” to it. [Candorville’s characters primarily are African Americans and Latino-Americans]. One editor said that maybe I should change the characters to animals. I held my tongue because I thought I’d probably sell the guy some work at some point, but I thought, “You’re telling me that animals are more ‘relatable’ than black people?”

Also, I had unpleasant experiences at good old liberal Cal. I was accused repeatedly of plagiarism. I always showed my instructors the first drafts of my work, and I thought, well, this must be commonplace. Everybody who comes to Cal was at the top of their high school class, and the writing level is very high, so naturally there’s going to be some suspicion. But after a while I noticed it was invariably the poorer and darker students who were accused. Finally, I got fed up. I went into one professor’s office without my usual supporting documents, and I decided to make her prove I hadn’t written my paper. She said, “Is there anything you want to tell me?” I responded, “No, is there anything you want to tell me?” And she said, “It doesn’t seem believable to me that you could write essays on par with what I’m reading here,” and she gestured to the books on her shelves. I told her to point out the passages she thought I’d copied. And then we both sat there saying nothing for the longest time. I could see she wanted to say things that she felt she couldn’t say. Finally, after several minutes, she said I could go. On the way out, I thought that I was always going to remember this moment, and I wanted to say something that felt cinematic, that would be the kind of line you’d say at the close of a dramatic scene in a movie. So I turned around and said, “If the writing was that good, I expect an ‘A.’” She just sat there and looked at me. Leaving that room without her saying another word felt like a deep vindication. It drove home that I didn’t have to take that stuff. I’d spent several years trying to disprove their accusations, and I finally realized that all I had to do was stand up and say, “Enough!”

And did you get an ‘A’?

I did.

You mentioned your grandfather’s experiences with discrimination. Could you tell us more about that?

I’m planning to do an illustrated memoir that would parallel my grandfather’s experiences with my own. Really, his life was a constant struggle—institutionalized discrimination made it difficult for him to find a job, almost any job, because of his race. He did enlist in the Navy during World War II and served aboard the [cargo ship U.S.S] Alhena at Guadalcanal. But while the Navy accepted African Americans, it was a segregated, racist system. They were restricted to lower ranks and were treated terribly. When he was at Guadalcanal, the Alhena was torpedoed and almost sank. There was a lot of carnage and terrible suffering. My grandfather said that there was one white guy in particular who was just a horrible racist. He was always telling my grandfather that he’d better watch out, he wouldn’t see it coming, but he was going to get it one day. And [the white man] was killed, completely decapitated by the torpedo explosion. My grandfather said the black sailors all gathered and celebrated after that, just because the guy who had tormented them so much and for so long was dead.

I saw some footage taken of the Alhena. Everyone was running back and forth on the deck. And I noticed that all of the gunners seemed to be white. I knew there were a lot of black sailors on the ship, and I asked my grandfather about that—why there weren’t any black sailors at the guns. He said first, African Americans weren’t allowed to fire the guns because the officers were worried they might swivel them around and shoot at the white crew. And second, [the African American sailors] weren’t that enthusiastic about manning the guns. No Japanese had ever called them n….r.

Has your life changed significantly since the Pulitzer?

To some extent, but it’s unclear what it will ultimately mean. I’ve had offers to adapt Candorville to TV and film. I might sign with a literary agent for my memoir and some children’s books. I recently came up with an idea for a children’s book that would’ve really interested me as a kid. It would be based on one year of my own childhood, sometime around the fourth grade, about what happened when my parents went through a divorce and how art helped me cope with it. I sent an outline to an agent who has successfully shepherded book series by cartoonists I know, and he loved it, so I’m refining the concept.

One thing I’ve had to do recently is change my working situation. I had been working out of the house, with my office separated from the rest of the rooms by a toddler gate. And it was great. I could work for a while, then step into the next room and play with my kids. But my son got big enough to climb over the gate, and then he spent most of his time sitting on my lap ‘helping’ me with my work. So I had to get a studio.

How is that working out?

It’s easier to work, but when they were in the next room I felt I was there for every moment of their lives, and I really miss that feeling.

It seems like a lot of possibilities are opening up for you. Do you ever see yourself abandoning cartoons for other options? Or even retiring altogether, as some cartoonists do mid-career?

If I stopped the strips and editorial cartoons at this point I’d feel like I’d be going AWOL. We’re at an inflection point for our country, and I can’t think of any other time when my work, what I do, would be more useful. I never thought I’d see anything like this, but I really believe our democracy is on the line. I don’t want to be in a position where my grandkids ask me what I did when Trump was president and I have to say I took a couple of years off to work on my memoirs. I want to be able to hand them a big book of cartoons and say, “This is what your grandfather did.”

From the Summer 2019 issue of California.