It was Berkeley in the 1920s. “The Fighting Swede” was driving through town, feeling even more pugnacious than usual. That’s because he was drunk. The Swede had carved out a reputation as a barroom brawler in the waterfront dives on both sides of the Bay, and he was always more than willing to defend his title—especially when he had a snootful of booze.

So he didn’t feel particularly tractable when a cop pulled him over at Ashby and San Pablo.

And not just any cop. As the officer unfolded himself from his squad car, The Swede realized the man was gigantic—over 6 feet and north of 200 pounds. What’s more, the man was a Negro, the first black cop The Swede had ever seen. When the officer told him to get into the squad car, The Swede balked.

“I’m not going,” he said.

“Oh, yes, you’re going,” said the policeman. “You’re under arrest. Driving while drunk.”

The two squared off, and The Swede came to the rapid and unfamiliar conclusion that the officer was right: He was being handled.

The cop had a billy club in his hand but tossed it aside. “I think I can handle you,” he said.

The two squared off, and The Swede came to the rapid and unfamiliar conclusion that the officer was right: He was being handled. The Swede struggled until the policeman delivered what he later described as “a light tap” to the jaw.

In the lock-up, the brawler’s face swelled like a ripe cantaloupe. Next morning, the cop stopped by his cell, and the men palavered. Sober now, The Swede felt chastened. For his part, the officer said he wasn’t going to file charges for assault or resisting arrest. Just drunk driving.

The cop, The Swede decided, was all right … for a Negro.

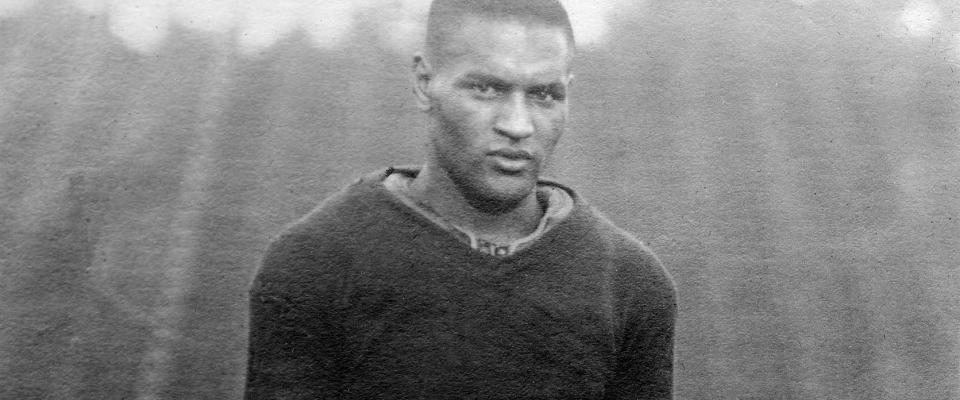

That noir-ish tale is based on a true account, told to an interviewer for the Bancroft Library Oral History Archives by the story’s protagonist, UC Berkeley graduate Walter A. Gordon, the first black police officer in Berkeley. Those transcripts provide significant historical context—and perhaps, ultimately, some insight—for anyone trying to understand police violence and race relations in the age of Black Lives Matter.

Walter Gordon was a man of many firsts: the first All-American in football at Cal, the first black All-American on the West Coast (actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson was the first on the East Coast), and the first black graduate of Boalt Law School. He joined the cops in 1919, only after Berkeley’s famed police chief August Vollmer, convinced him that he could do both things at once; namely, walk a beat and earn his J.D.

And Gordon did it, working the overnight shift with the department, when inebriates like The Swede were on the prowl, attending classes in the early mornings, and studying in the late afternoons after catching catnaps. Somehow he also managed to assist and scout for Cal coach Andy Smith’s legendary Wonder Teams.

By the time Gordon sat down on April 19, 1971, to record his reminiscences for posterity, more than 40 years had passed since he’d left the police force for private law practice. He had just retired as a federal district judge in the Virgin Islands, where he had also served as governor.

Gordon’s erstwhile chief, August Vollmer, was also a man of firsts. Under Vollmer, Berkeley was the first police department to install two-way radios in patrol cars, the first to insist that new hires be properly trained and educated, and the first to establish a modern crime lab. Chief Vollmer maintained a lean budget, yet still paid his patrolmen more than any department of comparable size in the United States.

In the early years of the 20th century, Berkeley, though considered less corrupt than its larger neighbors, was nevertheless rife with gambling parlors and opium dens.

Vollmer was born in New Orleans in 1876 and moved to Berkeley with his family at age 15, acquiring little more than a grade-school education by the time he reached adulthood. A veteran of the Spanish-American War, he worked for four years as a postman in Berkeley, where he impressed his superiors with his steadfastness. He even became something of a local hero after stopping a runaway rail car from colliding with a commuter train.

Urged to run for town marshal, he won the election handily, running on a platform of clean governance. In the early years of the 20th century, Berkeley, though considered less corrupt than its larger neighbors, was nevertheless rife with gambling parlors and opium dens. Already, the University’s reputation was stellar, and the people who counted wanted the town rehabilitated. Electing a man like Vollmer as marshal seemed like a good place to start.

Vollmer took office in 1905, the year before the Great Earthquake swelled Berkeley’s population with San Francisco refugees, thousands of whom inhabited encampments on the University grounds. To keep the peace, the new marshal deputized more than a thousand citizens and was happy to let spread a rumor that martial law was in effect.

But the Bay Area was no longer the Wild West, and the new marshal was no Wyatt Earp. Vollmer came to office at the height of the Progressive Era, that period of political reform spanning the 1890s to the 1920s. In the spirit of the times, he extolled “scientific police work,” not rough justice. He rejected the “third degree” (the common practice of beating confessions out of suspects), calling its use “an admission of stupidity and ignorance and brutality.”

“A lot of [cops] were corrupt and violent before Vollmer’s administration,” says Charles Wollenberg, professor of history at Berkeley City College and author of Berkeley: A City in History. “Vollmer was [a leader] in changing that, by insisting that his police officers were professional, well educated, and honest.”

This was the idea driving Vollmer’s “college cops” program, of which Gordon was an early exemplar. Many of Vollmer’s college hires went on to become police chiefs in their own right. Their successes, the innovations he championed, and a talent for promoting all helped to cement his fame. At its height, Vollmer’s police department enjoyed an international reputation and was even singled out for praise by Scotland Yard.

“He went beyond many other reformers,” says Wollenberg. “For example, he felt that police shouldn’t be involved in drug law enforcement. He thought drug abuse was a medical issue, a social issue—certainly not a police issue.”

Vollmer wanted his police to function as social workers, not just as crime fighters. One of Vollmer’s officers paraphrased the Chief’s speech to new recruits: “I’ll admire you more if in the first year you don’t make a single arrest. I’m not judging you on arrests. I’m judging you on how many people you keep from doing something wrong. Remember you’re almost a father-confessor; you’re to listen to people, you’re to advise them.”

Vollmer was also a fierce defender of free speech and staunchly opposed to capital punishment. In a 1934 letter to the local American Legion commander, he urged allowing Communists to make public speeches whenever they wished. “I would give every soap orator in the state a free soapbox, and I would let him talk until he needed throat tablets,” Vollmer wrote. “If we haven’t sufficient arguments to prove our principles of government, then we should sink. Our present practice is to make martyrs out of dumbbells.”

He was also against the use of the National Guard for the suppression of riots, because men trained for war tend to “shoot or club upon the slightest provocation.”

Skeptical of government, he was often unrestrained in his criticism of entrenched interests. In 1926, after three months spent in Detroit advising the city’s police department, he belabored the city’s courts in a press interview, calling one judge “a lazy psychopath” and two others “political favorites of the underworld.”

But perhaps his most courageous and iconoclastic act was simply to put a black man in uniform, give him a gun and a badge, and send him out onto the streets. After all, when Vollmer hired Gordon, Jim Crow still reigned in the South, lynchings were commonplace, and Ku Klux Klan rallies were regular occurrences in Oakland.

Upon news of Gordon’s hiring, several of Vollmer’s men openly rebelled. As Gordon’s friend, baseball legend Harry Kingman, told the story, Vollmer responded “Well, gentlemen, I’m awfully sorry that you feel that way. And, as you go out, you’ll notice there’s a table by the door; just leave your badges on the table.” That was the end of the insurrection.

There were other black police officers in America before Walter Gordon. The earliest, according to W. Marvin Dulaney’s 1996 study, Black Police in America, were “free men of color” in early 19th century New Orleans, whose primary responsibilities included catching escaped slaves. Samuel J. Battle became the first black officer in New York City in 1911 and walked a beat in Harlem. Gordon was unusual in that he was not assigned to patrol a predominantly black population. Berkeley’s African Americans constituted only about 1 percent of the city’s population at the time, and Vollmer assigned Gordon to patrol white residential neighborhoods, despite citizen complaints.

So what kind of police officer was Walter Gordon? According to William F. Dean, who served with Gordon on the city’s police force and went on to an illustrious military career as an Army major general, he was an acolyte of the Chief. “He often quoted Augustus Vollmer,” Dean told the Bancroft archivist. “[He’d say,] ‘We’re not out to punish people; we’re out to prohibit them, prevent them from harming society.’ That was his belief, and he lived up to it.”

That’s a far cry from the message given to today’s police recruits. According to John Thomas, chief of the University of Southern California’s Department of Public Safety and a member of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives (NOBLE), “Over the last 30 years, the departments have promoted law enforcement as a kind of adventure. They’ve fostered a warrior mindset more than a guardian mindset. In our training, we’ve sacrificed interpersonal skills and communications. Officers have insufficient knowledge of the communities they patrol. Now we have to remedy these missteps.”

Former Los Angeles police chief and NOBLE member Bernard Parks observes that community-based policing of the type championed by Vollmer has long since fallen out of favor. “We’ve moved away from that,” says Parks. “Today, police ‘community outreach’ tends to take the form of programs that teach kids how to play football, for example. But black communities are the same as any other community. Black people simply want police to do their jobs properly. They prefer an officer who responds to a call at 3 a.m. and deals with it competently, to one who teaches a kid how to throw a ball.”

Parks and others would like to see more outreach directed at recruiting young black men and women to become police officers. Critics, he acknowledged, complain that such efforts will “contribute to a reduction in quality. This is not so. Young women were not in sports at one time, and now they are. That’s because outreach programs were established. We are not lowering standards by reaching out to the black community. We are protecting an investment [in community stability].”

Parks added that it’s not enough to put more black cops on the street. African-American officers must be promoted to the executive ranks, where policy is forged and implemented. Discrimination at the highest levels is more subtle now, he says, but the chance of black officers being promoted when all their commanders are white is slim. “We used to say chiefs promote in their own image. So unless we have increased diversity at all levels, this will remain a problem.”

Walter Gordon left the police department in 1930. By then he had already become president of the Alameda County chapter of the NAACP. He kept a law office on the corner of San Pablo and University, not far from his home in West Berkeley—the “ethnic” part of town where most blacks lived. Gordon never did move to another part of town. That could have been from a sense of community solidarity, or it may have been due to a lack of options. “Many of Berkeley’s upscale neighborhoods had restrictive covenants based on race,” noted Wollenberg. “There may not have been many places he could have lived other than western Berkeley.”

Even today, of course, segregation persists—segregation of a de facto nature, enforced more by brute economics and class dynamics than by any overt policy aimed at keeping the races separate. Police reform will do nothing to change that. Society as a whole has to change. As the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates put it, “A reform that begins with the officer on the beat is not reform at all. It’s avoidance. It’s a continuance of the American preference for considering the actions of bad individuals, as opposed to the function and intention of systems.”

“Society needs and must somehow obtain truly exceptional men to discharge police duties,” Vollmer wrote. Some would no doubt argue that the police, no matter how exceptional, are still enforcing the laws of a corrupt society, and as such will continue to be regarded by the disenfranchised as a hostile army of occupation. But even if one concedes the larger point, ignoring the cop on the beat is a mistake. Police reform is needed in any case if race relations in America are to improve.

Perhaps Vollmer was naïve to think that police officers could be the enlightened übermenschen he envisioned, but at least he had a vision, one engendered by good intentions and an innate sense of social and racial equity. These days, says former LAPD chief Parks, too many officers simply “want to do police work and go home alive.” But that, Parks advises, is not sufficient to justify a career in law enforcement.

“No one is asking officers to die,” he said, “but we also ask that they don’t shoot just because they’re scared of not going home alive. We ask them to use tactics aimed at preserving the lives of citizens. We ask them to develop relationships with the communities they patrol, because in any given population, there are about 2 to 3 percent of the people who won’t comply with the laws; and if you don’t have community support, you will always have difficulties dealing with that 2 to 3 percent. The police and the public must have an active partnership for law enforcement to succeed.”

Glen Martin is a frequent contributor to California.

First image, Walter Gordon, Credit: Cal Athletics. Second image: August Vollmer, Credit: Library of Congress.