Kyle Kurpinski walks into his lab in the drab barracks of the Berkeley bioengineering field station in Richmond and opens the door to a stainless steel box about the size of a small refrigerator. Inside is a rectangular device with gears on one side that looks like a flat, miniature version of a torture rack. It turns out, that’s exactly what it is.

These days, most bioengineers are working on ways to get adult stem cells to change from mysterious nomadic loners into useful body tissue. Kurpinski explains that while many researchers are trying to alter stem cells with some kind of chemical cocktail, his team is looking into physical manipulation. “Chemical cues do some things, but they’re not the only things that happen in the body,” he says. “Our lab is interested in physical cues.”

Kurpinski holds a rectangular bag of Styrofoam that represents a single bone marrow stem cell, pulling and manhandling it as if he’s going to rip it open. By stretching and releasing a sheet full of stem cells in this way on his rack—five percent, once a second, for three days or so—he can partially convince them that they are not stem cells but actually smooth muscle cells, the elastic cells around an artery.

He says researchers are taking “a silicone membrane and basically putting a bunch of cells on there. And it’s not stretching one cell at a time, it’s stretching half a million.”

In the body, pulsing veins and arteries signal passing stem cells to change into muscle cells and attach to blood vessels. By forcibly stretching stem cells like fresh pizza dough, Kurpinski says he and his advisor Professor Song Li may be able to mimic what happens naturally and convince the cells to mutate.

Kurpinski says surgeons armed with a complement of brand new arterial cells may be able to rethink how bypass surgery is performed and even create new arteries for heart patients. The technique has been successful, and so far he and Li have managed to change the stem cells about halfway into muscle cells.

Researchers have known for years that stem cells are sensitive to “physical cues” and some have even experimented with stretching the cells. But no one else has gone as far as the Berkeley team, stretching the cells as much or from as many different angles.

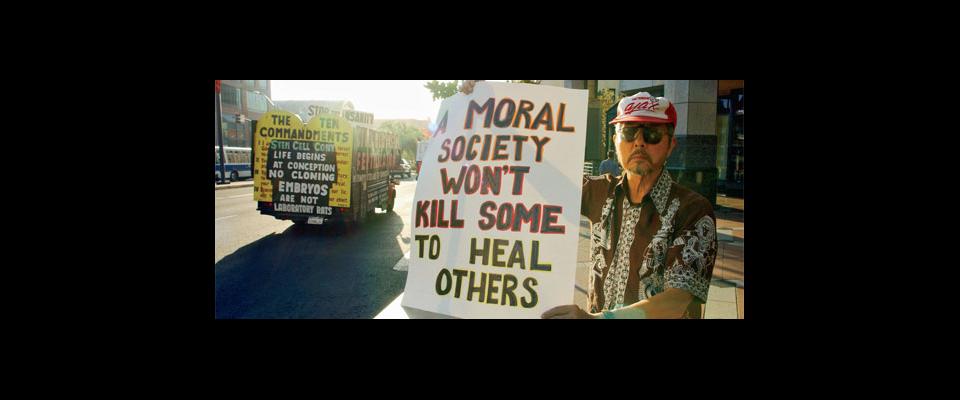

So far, only adult cells—like the kind found in marrow that form connective tissue—have gone through Kurpinski’s grueling regimen. These cells don’t require human embryos but have a limited number of incarnations that they can possibly change into. Some day he hopes to strap embryonic cells—which can theoretically become any tissue in the body—to the rack, but he worries about the politics surrounding their use.

“There’s so much controversy over embryonics right now,” Kurpinski says. “It’s almost better if you could get the adult stem cell to do what you want it to. Then you don’t even have to worry about it.”