As LA continues to burn and a blanket of smoke, ash and toxins covers Southern California, an atmosphere of dread hangs in the air over Berkeley and the fire-prone East Bay. Are we next?

The lush landscape of forests with homes nestled into the Berkeley hills is beautiful to behold for many aspiring homeowners. But for Michael Gollner, Associate Professor in Mechanical Engineering at UC Berkeley, it’s terrifying.

Gollner studies the mechanics of fire: how it ignites, grows, behaves and dies. He got his PhD at UC San Diego before moving to Berkeley in 2020. His research takes the theoretical physics of fire and explores real-life applications for that knowledge, including the development of models that can help clarify the path a fire may take and predict the likely behavior of each ember released.

Gollner’s research helped adapt an open source wildfire model, ELMFIRE, to track how fires move beyond wildlands and into communities. With his tool we can better predict potential damage, calculate risk and identify the effects of different mitigation choices. According to Gollner, the research helps illuminate how wildfires spread into communities and “hopscotch” through residential areas.

California recently spoke to Gollner about the inevitability of fire in Berkeley and what campus and the community can do to avoid the worst outcomes.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity

What are you most concerned about when it comes to Berkeley’s campus and the Berkeley area’s susceptibility to fires?

We know that the Hill Campus is at huge risk. We also have a lot of chaparral scrub and oak scrub. We are susceptible to the Diablo winds and there are some structures on the edge of campus that [may require] structure protection. We only have a small portion of the hill, and behind that is Tilden Regional Park, and then you have homes all along it. It’s terrifying driving through the Berkeley hills. You have wood siding and still have some wood-shingled roofs and wood fences and just vegetation everywhere surrounding people’s homes. It’s a continuous path. If a fire were to move through, it can just jump from one thing to the next.

Embers will continue to hopscotch through the community and it will be near impossible to stop under the highest wind conditions. At that point we need to worry more about evacuation. Campus obviously recognizes that risk.

There’s been a lot of mitigation on upper campus to try to lower the risk, especially in the evacuation routes. It’s primarily in terms of thinning or clearing vegetation. These mitigation efforts are critical for enhanced fire safety on campus. The focus has primarily been on [removing] fuel near evacuation routes which is incredibly important for life safety. Eucalyptus is a large problem.

What lessons from the LA fires do you think can be applied to the Berkeley area? What are we not doing that we should be?

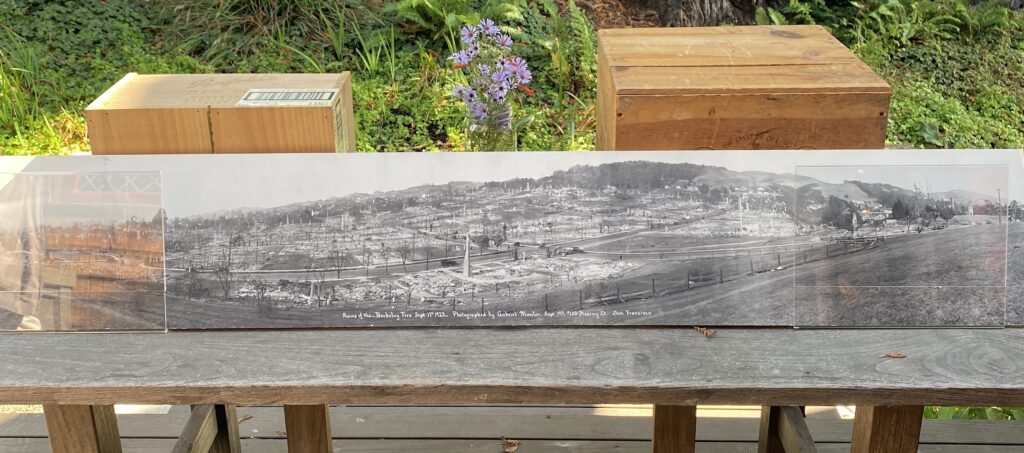

For the Berkeley area, I hope it’s a wake up call. It’s a reminder of the 1991 Tunnel Fire, which happened in the Oakland Hills. If you go further back, the 1923 Berkeley fire footprint went right up to the building that I have my office in. And that should be a wake up call that fires can spread all the way into our area.

We knew that the Palisades was a high risk area in LA. You don’t think about it when you’re in a suburban community, but embers have long transport distances. In Altadena, firefighters reported embers traveling over two miles from the flames. You can imagine how that scenario could be disastrous for us.

In the central campus, there’s a lot of clearing, a lot of open space. There’s not as many opportunities for things to ignite, but that is not consistent in all buildings and all areas, especially on the fringe.

My biggest concern is whether fire regulations are going to be waived or watered down. We should enhance these measures as we rebuild so that we won’t experience this level of destruction again.

What are some of the mitigation efforts local residents should be taking?

We think of two types of mitigations around homes. The first is defensible space. It doesn’t mean bulldozing around your house: it’s design principles. Within five feet around your home, you should have nothing flammable. You can have islands of trees but spread that out. Make sure things like wooden fences can’t bring burnable material to a structure. Make sure that those [fences] aren’t touching [the house or] within five feet, so the flames can’t touch.

And then, to actually redesign the structure: it’s not about building it out of concrete; it’s about making sure that the exterior is not ignitable by the embers. You don’t want wood shingles on the side or the roof. You want to enclose eaves. You want screens on vents, or better, ember-resistant vents, double pane windows, siding that’s not flammable, decks that aren’t touching the house.

And this is hard when you have neighbors. Everything is very close, given the market and the design that happened so many years ago here. It’s going to require a community-wide approach, because if any of those homes catch fire, it starts spreading from home to home. It has to be a whole community effort.

There are a lot of pictures from LA where a house has burned to the ground but trees in the landscape are left standing. What explains that?

Wildfires spread in communities three ways: First there’s radiation. Next is direct flame contact. So, there is grass or a fence, and [even if] it’s just a small flame spreading along, if it connects, it’s just like dominoes, all the way to the house. Third is embers. These fly and start new fires, but they don’t just instantly light something on fire. The wind picks it up. They land. They have to smolder. They catch something else. It grows. 99.99 percent of embers do nothing, but there are billions of them.

Trees are typically a ways back from the structure, so [they’re] not going to be [ignited] by direct flame contact.

Trees don’t typically ignite by embers; there isn’t a lot of dead litter on a tree to ignite. But if embers get in through a vent into the attic, the house burns from the inside out. It collapses. Embers fly everywhere and there’s a lot of flames, but never quite enough to ignite that tree.

You need a lot of radiation for a green, live tree with moisture to ignite. And there’s nothing connecting the house to that tree, and so it doesn’t [always] happen. Sometimes it does but it just depends on the direction of the wind.

So, turning to the actual fighting of the fires, how do water and fire retardant drops work? How effective are they?

Suppression is very effective early in a fire, or when it’s small. If you’re dumping lots of water or retardant right in front of a community, you can have an effect. You can’t stop the fire; it is just too much force to contend with. But you can protect things, and we’ve seen the aerial bombardment dramatically increase in California. It can land on the fire and sort of put it out but for the most part, it works by cooling the fuel.

Retardant is basically water, but it also has other things in it to help it bind, making it harder to evaporate. The fire retardant is just slowing the fire down by being harder to vaporize.

There is a 1998 article being resurfaced this month for obvious reasons called “The case for letting Malibu burn.” Is there a case for not rebuilding Malibu in the aftermath of these fires? Or rebuilding it differently?

There is the concept of retreat and [those who expound it] have a point, but I think it’s a little difficult.

When you look at California and you actually draw out the areas that are under threat from wildfires, you realize the scale and the impossibility of rehousing so much of the state. I don’t think there’s any practical sense that we’re going to move out of there. There’s nowhere else to put people. Instead, we have to take it like an engineering problem and say, “Well, what can we do to make this better?”

I think there’s a lot of things we can do, but we have to buckle down and implement them. If Malibu was completely new, we’d have many opportunities for design. But we’ve already got the layout and people own the property, so I will accept that we can’t change that. We can reexamine evacuation routes, and the way fuels are managed. What are we going to do as fuel builds up? Are we going to create barriers? Are we going to have management plans? Are we going to keep [vegetation] down so that the risk in this area never gets as high as it was before?

With those limitations in mind, what do you hope rebuilding in the future looks like?

My biggest concern is whether fire regulations are going to be waived or watered down in any way. In my opinion, we should enhance these measures as we rebuild so that we have a model community that won’t experience this level of destruction again.

California does have California Building Codes that regulate construction in wildland urban interface areas. A lot of these things are technically regulated, but in the past, [those regulations have] been suspended after a fire. So hopefully they stay [in place and are enforced] this time.

I think it’s a given that we’re going to allow residents to rebuild in the same footprints. California Building Code Chapter 7A specifically requires home hardening, and I hope that remains enforced, as well as several laws that relate to defensible space around homes. It would be great if there was a concerted program in areas affected by the fires, including training for residents, architects, installers, inspectors and grant support to help rebuild the community following the best science today.

I think we’re going to see the impact when [the models] are used in design. These sorts of questions can now be tackled: What if you apply these mitigations here? What if you did that there? What would be the cheapest way to do this? Where could you make the biggest impact for the least cost?

There’s not going to be a magic vaccine to protect communities from wildfires. Instead, as engineers we can create the tools to make it much easier to implement fire-safe features where they can have the greatest effect.