The recipients of the Cal Alumni Association’s Alum of the Year Award are an impressive group, to say the least. The list includes decorated military officers, Supreme Court justices, Nobel laureates, leading industrialists, and renowned authors. None, as far as we know, ever dropped out of the University.

That has now changed with the addition of 2015 Alumnus of the Year Stephen G. Wozniak, who left UC Berkeley in 1972. More than a decade later, he returned to complete his degree—after cofounding Apple Computer, now known as Apple Inc., currently the most valuable technology company in the world.

An electrical engineer, Wozniak is credited with having designed the company’s earliest products—most notably, the wildly popular Apple II—which helped spark the revolution in personal computing. For his contributions, he has been honored with a Heinz Award for Technology, the Economy and Employment; induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame; and the National Medal of Technology. But speaking by phone from his home recently, “Woz,” as he is best known, insisted that receiving his diploma on the stage of the Greek Theatre was his life’s “proudest moment.”

The Woz first attended Cal in 1971, after a year at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “I fell in love with snow,” he said of his out-of-state flirtation. Two things lured the San Jose native back from the Front Range. First, The Graduate had just hit movie theaters and its portrayal of Berkeley made an impression on the young Woz. Second, and more important, Berkeley was famous as the home of the Free Speech Movement.

“It made up a huge part of my life [and continues] until this day … especially speaking out against the [Vietnam] war. They were standing up for different kinds of human rights…. Maybe because I’d been a geek and I’d been shunned … I always cared about people that cared about other people.”

If Cal’s activist culture was the “software” that attracted Woz, he was also drawn to Berkeley’s impressive hardware. “They had a real top supercomputer—a CDC 6600—that was an amazing part of my life.” Significantly, the storied mainframe, used by the Lawrence Berkeley Lab to trace nuclear events in Donald Glaser’s bubble chamber, wasn’t restricted to grad students; Woz had access to it even as an undergrad.

“My roommate, John Gott, wrote a ten-page report—his final for an English class—and it was all about my escapades that year, and he called it fiction because nobody would believe it.”

In his spare time, Woz pursued some very unauthorized extracurricular activities, chief among them the lost art of phreaking. Phone phreaks were a subculture of rebellious techies who figured out how to hack the AT&T telephone network. The primary tools of the trade were home-built “blue boxes”—electronic gadgets that could generate the audio tones used by the phone network to do simple things like dial numbers. With a blue box, you could call long-distance (an expensive proposition at the time) for free.

Wozniak recalled that these exploits around the edges of the emerging tech scene—often with Steve Jobs and other friends—“led me into being a leader in my dorm.” Jobs, who died in 2011, would of course go on to become Wozniak’s cofounder at Apple. Back then, they were known to other phreaks by their handles: Woz was “Berkeley Blue,” and Jobs was “Oaf Tobar.” Recalling those days, Woz says, “My roommate, John Gott, wrote a ten-page report—his final for an English class—and it was all about my escapades that year, and he called it fiction because nobody would believe it.”

One such escapade involved pyrotechnics, popcorn, and some 40-pound-test fishing line strung between the seventh-floor lounge of Norton Hall and the first-floor lounge of Ida Sproul Hall. Woz and his buddies had recently driven to Tijuana to buy fireworks. Now they were attempting to convey the contraband explosives “right over the garden of the housemother” at neighboring Unit 3 dorm. It didn’t quite work as planned, but they were proud enough of their effort to leave a signature behind. “We wrote down all the physics of the friction, and the angles, and the estimated time the fuse would burn, and how long the fuse should be … and we left it on the blackboard of the seventh-floor lounge so they’d find it after we did it.”

Long before Lifehacker, Woz loved coming up with novel solutions to life’s challenges. When he needed to create decks of punch cards for the mainframe computer, he was frustrated that “at finals time, you’d have to wait 40 minutes to get a keypunch.” Noticing there were no lines for some older keypunch machines with obsolete keyboard configurations, he just worked out what key combinations were needed to get the desired results. “You’d see different characters on the screen, but you’d get the right holes on the cards,” he explains.

That might seem like more trouble than it was worth—more in keeping with the cartoon contraptions of Rube Goldberg (Class of 1904) than with Apple’s minimalist designs. But Woz also developed an appreciation for simplicity at Cal—when paying for his Top Dog, for example. In his 2013 commencement address at Berkeley, Woz praised the Berkeley wiener vendor’s pricing structure—whole numbers, no tax. It meant you didn’t have to dig into your pockets for change. “It’s so simple and nice for the buyer,” he told the assembled graduates. “That inspired me and my computer designs so much…. I like to put that simplicity into all of my designs … [to] get the details out of the way.”

Of course, it wasn’t all hijinks and hot dogs. Woz took his classes at least as seriously as his pranking. Not that studying was ever especially challenging for him. He says he’d buy the course’s text at the beginning of the semester and “go through every page in the book. I’d answer every question at the end of each chapter, and I was halfway through the book by the time class started.”

When he left school in 1972, he didn’t expect to stay away as long as he did. “My original experience at Berkeley had been probably the best year of my life,” he says now. “I didn’t ever drop out,” he insists. “I took a year off to earn the money for my fourth year.”

He’s not afraid to be goofy or cut loose. Other technorati retain image consultants. The Woz plays Segway polo with his team, the Silicon Valley Aftershocks. And who can forget his stint on Dancing with the Stars with partner Karina Smirnoff?

And that he certainly did. After a few short-lived ventures—selling blue boxes, running a Dial-a-Joke service—outside his day job working on HP calculator chips, he showed off a little something he’d been tinkering with to the engineers at the legendary Homebrew Computer Club, cofounded by Berkeley activist Fred Moore. That “little something” would eventually become the Apple I, and it would change Woz’s life, as well as the lives of everybody who uses a personal computer (or a smartphone or tablet or smartwatch) today.

Woz may have entered the Silicon Valley pantheon, but he’s always had a tendency to “think different” from his peers. Most other tech VIPs entertain themselves at exclusive parties and in private skyboxes. They hobnob with world leaders and rock stars at places like Davos, Switzerland. Woz, though, can be found hanging out at Outback Steakhouse and Denny’s. When he comes to Berkeley, he’s still liable to go for a Top Dog and then share that info via @stevewoz on Twitter.

He’s not afraid to be goofy or cut loose. Other technorati retain image consultants. The Woz plays Segway polo with his team, the Silicon Valley Aftershocks. (The world championship of Segway polo is the Woz Challenge Cup.) And who can forget his stint on Dancing with the Stars with partner Karina Smirnoff?

His best-known pairing, of course, was with his friend Steve Jobs.

It’s not unusual for a business whiz to pair up with an engineering geek to start a company, the left-brain techie complementing a right-brain marketing type. In the usual division of labor, the engineer is focused on solving well-defined problems, such as how to make a product smaller, lighter, or cheaper to manufacture. The marketer’s challenge is more open-ended: how to make people care about, pay attention to, or even love that product.

Jobs was a marketing guy who often thought more like an engineer. His answer to an open-ended problem wasn’t merely an answer, it was the answer. Woz is an engineer who can see more than one answer to even the most well-defined engineering challenge. In his memoir, iWoz, he makes the case that the best engineers—the ones who think beyond the “artificial limits everyone else has already set”—are artists who “live in the gray-scale world, not the black-and-white one.”

Neither Steve fit neatly into the usual stereotype—and that may have been a key element to their success together. In his book Powers of Two, Joshua Wolf Shenk analyzed a number of famous partnerships—such as South Park’s Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the Beatles’ Lennon and McCartney, Jobs and Wozniak—and found some common characteristics. Reached by phone, Shenk said the two Steves had a perfect partnership.

“Part of what Jobs did was steer and direct Wozniak—goad him, inspire him, manipulate him. You get the sense it would take a real master to do that because Wozniak was not inclined to be directed by anybody. No amount of money or glory has ever been able to draw him to anything he didn’t want to do.” But, Shenk explained, sometimes the roles were flipped, with Woz steering Jobs in a new direction, away from his misplaced certainty.

“It’s easy to imagine that neither of the Steves would have done anything of significance had they not met each other.”

After a plane crash in 1981 left Woz temporarily afflicted with anterograde amnesia—loss of the ability to create new memories—he decided it was time to complete his long-postponed computer science degree rather than returning directly to Apple. As he recounts in iWoz, “I realized it had been ten years since my third year of college, and if I didn’t go back to finish up now, I probably never would. And it was that important to me. I wanted to finish.”

“Ten years had passed. I didn’t expect I’d be getting A+’s. People would be saying ‘Hey, how come this guy Steve Wozniak from Apple Computer is only getting B’s?’ So I thought I could ditch out on that if I had a fake name.”

Going back to school was a tough commitment—he would still have to juggle some responsibilities at Apple—but keeping his identity anonymous at Cal helped make it manageable. “My name was famous, but not my face,” says Woz, so he enrolled under the pseudonym Rocky Raccoon Clark (combining the names of his dog and his then-fiancée) partly to avoid drawing attention to himself, partly to avoid potential humiliation. “It’s not like I knew everything academically—ten years had passed. I didn’t expect I’d be getting A+’s. People would be saying ‘Hey, how come this guy Steve Wozniak from Apple Computer is only getting B’s?’ So I thought I could ditch out on that if I had a fake name.”

In addition to his engineering coursework, he also took graduate-level psychology courses in human memory, to help him better understand the impact of the plane crash on his own mind. He found the field of psychology fascinating and even contemplated switching his major. One of his most eye-opening lessons was discovering how common memory loss was for people who had survived crashes. He says he was baffled that his own doctors and psychologist didn’t know this. In general, Woz says, his continuing Berkeley education made him “even more skeptical” about many things.

To round out his education—and perhaps to decompress—he found time to head to La Val’s Pizza to play the video game Defender. “Playing games well becomes a big thing in your life.”

After graduating, Woz again bucked convention. Rather than go back to Apple, he went back to school—as a volunteer teacher of middle- and high-school students in Los Gatos. While teaching his fourth-grade son, Jesse, about computers, he discovered he had a natural rapport with kids, and was able to inspire one of Jesse’s schoolmates to turn her classroom performance around. He wanted to see if he could expand that experience to a classroom full of students.

He began with a group of six fifth-graders, teaching them the basics of hardware and software, and how to troubleshoot. They visited people across the planet in AOL chat rooms. And, incidentally, they learned to type while learning to communicate. As he notes in iWoz, “the primary goal was to teach them how to make their homework look good.” He would continue helping them in that task for eight years.

There have been other ventures and adventures in the life of Steve Wozniak. He has launched other startups (creating the first universal remote control and a GPS tracking system), served as chief scientist for data storage company Fusion-io, and played himself on an episode of The Big Bang Theory. His philanthropic initiatives have benefited the San Jose ballet, the Children’s Discovery Museum (located on Woz Way in San Jose), and his alma mater, where you’ll find a Wozniak Lounge in Soda Hall.

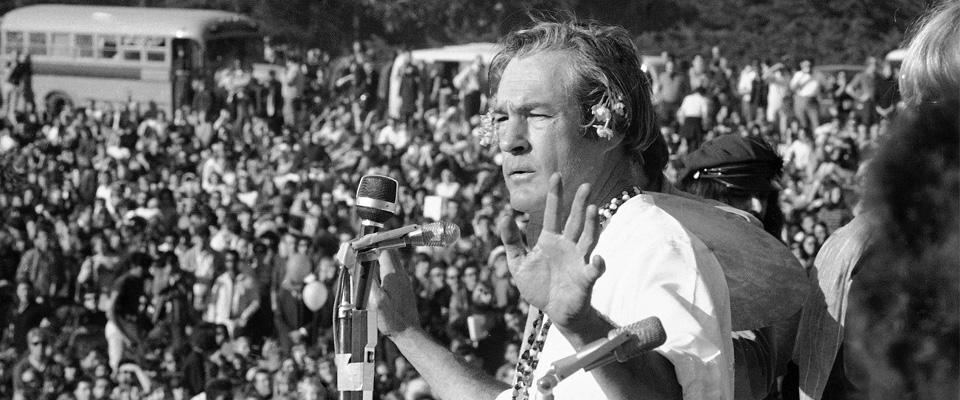

He also created and sponsored the two US Festivals in 1982 and 1983. Envisioned as a kind of Woodstock West, the name “US” was meant as a rejoinder to the self-centeredness of the Me Decade. The festival incorporated technology and politics, featuring, for example, live satellite links to the Soviet Union, along with an eclectic mix of music. In a recent documentary, Cal alum Stewart Copeland (drummer for The Police) remembered the now largely forgotten US Festival as having distilled “la crème de la crème de la crème” of talent, and stressed that it really “should be up there with Woodstock.” For that matter, US could also be seen as the distant relative of TED and Burning Man.

To all of these sundry ventures, the Woz has brought a mix of intellectual curiosity, skepticism, and empathy for the people and the world around him. Perhaps it is not surprising that those are all traits that drew him to the Berkeley campus in the first place.

“I didn’t want to be an activist, but I sure wanted to hang around it and understand it and observe it…. The people [who] were speaking—especially from an academic background, professors and very brilliant students—when they spoke, they had logic and reasoning as to why some actions of the United States were wrong and bad. The United States had no logic—they didn’t engage in a real discussion or debate on the issues.

“I wanted to be around these people that had brains that could think better and think carefully about things and lead us into good decisions…. Berkeley meant all of that to me, and it does to this day.”

Jon Zilber is a former editor-in-chief of MacUser magazine and has managed communications, marketing, and social media for the Sierra Club, TechSoup, and Palm. He can be reached via jonzilber.jimdo.com.