Most people don’t change their political stripes. David Horowitz isn’t most people.

It was the summer of 1970, and the war in Vietnam was never going to end. B-52s were carpet-bombing Cambodia, gouging craters into its eastern hills; across the border, angry G.I.s were fragging their officers. Back home, radicals were bombing police stations and burning down banks. In May, the National Guard shot four students dead at Kent State. To paraphrase Yeats, things were falling apart; the center couldn’t hold.

David Horowitz, a 31-year-old leader of the New Left and co-editor of the radical magazine Ramparts, had the answer: revolution. In the July 1970 issue, the cover of which depicted a Molotov-wielding, gas-masked protester, he and his co-editor wrote: “The system cannot be revitalized; it must be overthrown. As humanely as possible, but by any means necessary.”

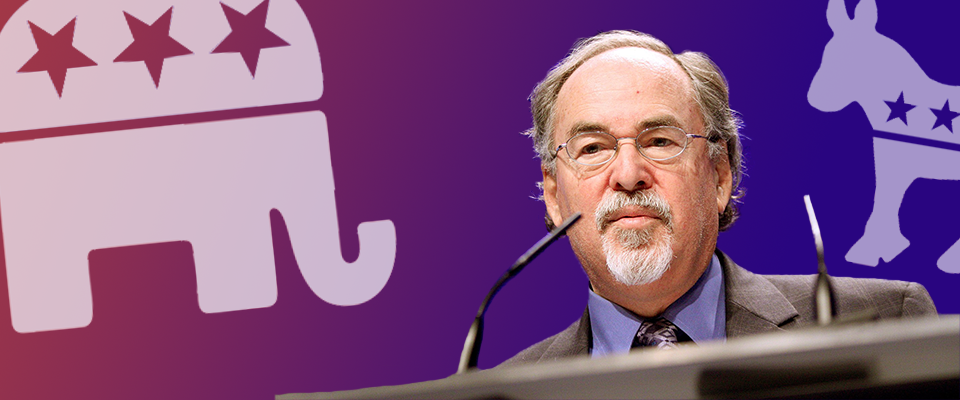

Horowitz once described himself as “the most hated ex-radical of my generation.” This is almost certainly true.

Almost 50 years on, as Donald Trump took office and pink-hatted protesters took to the streets, Horowitz was still manning the barricades. Now, however, he had switched sides. In early 2017, Horowitz’s right-wing foundation launched a campaign against “sanctuary campuses,” including UC Berkeley, which have pledged not to report undocumented immigrants to authorities. The first shot in Horowitz’s campaign was to be an appearance at Cal by alt-right agitator Milo Yiannopoulos, a conservative writer who had been banished from Twitter after a series of racist tweets. University officials feared that Yiannopoulos, who had singled out a transgender student during an appearance at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 2016, planned to “out” undocumented Cal students from the lectern.

As it happened, Yiannopoulos didn’t get to speak. Masked antifa protesters brandishing homemade weapons and M-80s descended upon Sproul Plaza and shut down the talk, prompting charges from the right (including President Trump) that Cal, home of the Free Speech Movement—and, by extension, the entire left—didn’t actually care about free speech at all. A couple of months later, a Horowitz appearance was canceled after school administrators and Berkeley College Republicans couldn’t agree over the venue, the timing, and security costs. Alleging that the University was suppressing conservative speech, the College Republicans and the Young America’s Foundation filed suit, which was settled last year with both sides claiming victory.

“The Berkeley administration has taken a page out of Orwell,” Horowitz declared bitterly. “Berkeley is a disgrace.”

Horowitz, who earned his master’s in English from Berkeley in 1961, once described himself as “the most hated ex-radical of my generation.” This is almost certainly true. A skilled provocateur who sees himself as at war with all the institutions of the left—Democrats, academia, the liberal media—Horowitz is known both for his uncommon political journey and for his ferocity. His stock-in-trade is the bloodcurdling denunciation: Barack Obama is a “communist and a traitor,” Black Lives Matter is a “racist organization,” Democratic calls to impeach Trump are “treason.”

We are all products of our environment, and most of us absorb our politics from our families and communities. Once set, these affiliations rarely change.

This combativeness might be Horowitz’s greatest influence on our national politics, helping clear the way for the likes of Sarah Palin and Ted Cruz, who share his love of political warfare. His fingerprints extend to Trump’s inner circle. Former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon hosted a Horowitz book party in 2013, and Horowitz’s foundation gave Bannon a Courage Award in 2017. White House immigration adviser Stephen Miller, meanwhile, made his bones in Horowitz’s student anti-political-correctness movement, first in high school then at Duke University.

Horowitz is suspicious of most media and declined to be interviewed for this story, which ultimately is an attempt to understand how a person can go from one political extreme to another, and what the rest of us might learn from that example. (“I don’t think I want to be any part of a hit job on myself,” he emailed in response to my final query). However, many of his current and former associates, including Berkeley grad Peter Collier, Horowitz’s co-editor at Ramparts, longtime collaborator, and fellow Berkeley alum, did agree to talk. Together, their insights may shed some light on the strange case of David Horowitz and our no-less-strange political moment.

Collier, who underwent a parallel political conversion, credits Horowitz (and, to a lesser degree, himself) with bringing the New Left’s take-no-prisoners attitude into conservatism. “We tried to infuse a fighting spirit into the movement.”

WE ARE ALL PRODUCTS OF OUR ENVIRONMENT, and most of us absorb our politics from our families and communities. Once set, these affiliations rarely change, according to Berkeley political scientist Eric Schickler, who co-authored a seminal 2002 study on voter beliefs and partisanship. When people do switch parties, the ideological shifts tend to be small-bore—from moderately left to moderately right, like the Reagan Democrats of the 1980s. Some of the most consequential changes, Schickler said, happen over the course of decades, not because individuals suddenly changed their views radically but because millions of people gradually moved in the same direction. The New Deal convinced Americans of the virtues of bigger government, while many white Democrats became Republicans in response to the Civil Rights Movement.

Conversion stories illustrate how deeply intertwined the personal is with the ideological, the tribal with the intellectual—and the costs of leaving the tribe.

Wholesale political conversions like Horowitz’s and Collier’s are rare but not unheard of. They often attach to revelations of atrocities or abuses of power. When news of Stalin’s Great Purge leaked out of Russia in the 1940s, for example, a wave of American leftists abandoned communism. Examples include the intellectual Irving Kristol, who founded the early neoconservative journal The Public Interest (and whose son co-founded the recently defunct conservative journal The Weekly Standard), and Whittaker Chambers, a spy for the Russians who turned to Christianity and declared communism a false god.

Later, like Horowitz and Collier had, a handful of notable sixties radicals soured on the revolution and went conservative, including New York writer Norman Podhoretz and Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver, who morphed from urban guerrilla to Moonie and Reaganite.

Others take the opposite journey, from right to left. In the 1990s, Berkeley alum David Brock, a self-described “right-wing hit man,” dug up (mostly fake) dirt on the Clintons and smeared Clarence Thomas’s accuser, Anita Hill, as “a bit nutty and a bit slutty.” Brock, who also declined to participate in this story, wrote in his 2002 memoir, Blinded by the Right, that it wasn’t just conservatism’s ideas that captivated him so much as its power: With Reagan ascendant, the right had all the juice in the 1980s. “Seeking a channel for my ambition, I was a perfect—and perfectly willing—instrument for the wishes of others,” he wrote. After defecting to the Democrats in the late 1990s, Brock founded Media Matters for America, which monitors right-wing news coverage. In that role, he has been a particularly staunch defender of his former enemies, the Clintons.

The latest political apostates are the “Never Trumpers,” a group of high-profile conservative writers, politicos, and think-tankers—including Cal alums and Washington Post opinion columnists Max Boot and Jennifer Rubin—who refuse to support Donald Trump on principle yet resist defecting to the Democrats. (One notable exception is Kurt Bardella, former Republican congressional aide and Breitbart consultant, who did cross the aisle. “I think it was the right thing to do,” said Bardella. “At the end of the day, you have to live with yourself.”)

Depending on your politics, these renunciants are either heroes or traitors. Conversion stories tell us about the nature of political belief, in how we come to our creeds, and how those creeds might change. They illustrate how deeply intertwined the personal is with the ideological, the tribal with the intellectual—and the costs of leaving the tribe.

Wholesale political conversions like Horowitz’s and Collier’s are rare but not unheard of. They often attach to revelations of atrocities or abuses of power.

Chambers, the ex-spy, worried that the party might murder him and took to carrying a knife. And while Brock’s watchdog organization quickly became a key part of the Democratic ecosystem, many on the left still regard him with suspicion.

“I still know liberals who say that, despite what he has done since his conversion, they’ll never trust him,” a former Media Matters staffer tells me.

No matter where they began on the political spectrum, each turncoat eventually reached a point few of us ever do: Their political homes become intolerable, so they set off for uncertain shores. For Horowitz, it took an earth-shaking event to topple his old faith.

BORN IN QUEENS TO COMMUNIST PARTY MEMBERS, Horowitz, now 80, grew up in a “hermetically sealed universe” of leftists. A stereotypical red-diaper baby, he practically suckled on Das Kapital. He marched in a May Day parade at age 9; Pete Seeger led sing-alongs at his summer camp. After the revelations of Stalin’s horrors, his parents quit the party but kept the Marxist faith. Horowitz, too, clung to socialism but vowed to redeem it, to “create a new socialist vision free from the taint that Stalin had placed on the movement.”

Arriving in Berkeley in 1959, he co-founded Root and Branch: A Radical Quarterly in 1962, the first journal of the New Left, and set about formulating a new take on Marxism. Former Berkeley grad student Sol Stern, a journal co-founder who also moved right in the 1970s, describes Horowitz then as “sweet, scholarly, brilliant and widely read.” He was also an activist: In 1961, his part in an anti-nuclear protest earned him a scolding from University administrators; the following year he helped organize the first American protest against the Vietnam War.

In 1962, he left for a six-year European sojourn, where he worked for the leftist philosopher Bertrand Russell and labored over books with weighty titles like The Free World Colossus: A Critique of American Foreign Policy in the Cold War and Empire and Revolution: A Radical Interpretation of Contemporary History. Although he missed out on the Free Speech Movement, his 1962 book, Student, on Berkeley’s burgeoning student movement, inspired Mario Savio to enroll at Cal.

Born in Queens to communist party members, Horowitz, now 80, grew up in a “hermetically sealed universe” of leftists.

By the time Horowitz returned to Berkeley in 1968, the counterculture was flourishing, with louder music, longer hair, and sharper-edged politics. The scholarly Horowitz was out of step: He had a wife and kids and wasn’t into drugs. “People were bezonkers here,” he told Mother Jones magazine decades later. “It was just hundreds of flowers blooming. Inchoate.” But the sense of imminence, of being on the cusp of epochal change, was intoxicating.

Many of his Berkeley friends had joined a new magazine called Ramparts, which was fast becoming the journalistic voice of the New Left, reporting on the CIA’s subversion of the student movement and cheering on the Black Panthers and Fidel Castro. Horowitz wasn’t the most radical of his peers, but he was swept up in the revolutionary excitement. Still, when the Weather Underground began bombing private buildings, he grew uneasy, writing articles that warned against what he saw as the movement’s anti-intellectual, totalitarian tendencies.

By 1972, with the war winding down and the revolutionary flame sputtering, Horowitz drifted into the orbit of Black Panther Party co-founder Huey Newton. Out of prison and dedicated to “putting down the gun,” Newton now claimed to be working within the system. The two hung out in Newton’s glass-walled penthouse overlooking Lake Merritt, talking dialectics and plotting the next steps toward utopia. Horowitz helped establish a Panther school and community center in East Oakland, even as he began hearing whispers of Newton’s brutal side. (Soon Newton would be arrested for killing a prostitute in Oakland and flee to Cuba). Horowitz, dazzled by the black militant’s charisma, swallowed his doubts.

Late in 1974, one of Horowitz’ friends, a Ramparts bookkeeper named Betty Van Patter, went missing. Horowitz had gotten her a job with the Black Panthers. When her body turned up the following month, floating in the bay, he immediately suspected the Panthers of killing her. (The murder remains unsolved.)

Van Patter’s death hit Horowitz like a hammer blow. He woke up in tears each day, agonizing over his role in his friend’s murder, cursing his naivete and bad judgment. Horowitz had aimed to rescue the left from the monsters of his parents’ generation, he reflected, but he was now as complicit as they had been: “My political odyssey had come full circle.”

Horowitz had aimed to rescue the left from the monsters of his parents’ generation, he reflected, but he was now as complicit as they had been.

“David was just blown out of the water,” said Kate Coleman, a Berkeley alumna and Free Speech Movement veteran who wrote for Horowitz at Ramparts and later published the first investigative story on the Panthers’ crimes in New Times magazine, using Horowitz as an anonymous source. “His guilt was overwhelming. He was really suffering.”

Even worse, few of Horowitz’s comrades seemed to care; there was no clamoring for arrests or outrage over the murder of an innocent. The Panthers, diminished though they were circa 1975, were still a powerful symbol of the revolution—one of the few leftist icons still standing. “Because the suspects were the Panthers themselves, it didn’t matter,” he recalled in his self-lacerating memoir, Radical Son. “The incident had no usable political meaning, and was therefore best forgotten.”

IT’S TEMPTING TO IMAGINE CONVERSIONS AS LIGHTNING STRIKES, but they’re more often like earthquakes; the ground shifts almost imperceptibly beneath your feet until, finally, everything gives way. “There’s a stage where something happens, and you begin to realize that your old identity doesn’t help you explain the world in quite as efficient of a way,” said Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, a Berkeley psychology professor. “It’s like, ‘My worldview doesn’t fit anymore. There’s holes in my story.’” Most people try to paper over the inconsistencies, he continues, “but whether it takes or not is a different story.”

As the 1970s waned, Horowitz soldiered on, trying to reconcile his birthright Marxism with his growing cognitive dissonance. With Collier, he co-authored bestselling books on the Rockefellers, Kennedys, and Fords, and tried to make a career as a garden-variety liberal intellectual. Leaving the left—the only community he had ever known—seemed inconceivable, but he struggled with his guilt and was increasingly shunned by his former comrades.

Their coolness is understandable, said Daniel Oppenheimer, who profiled Horowitz for his book, Exit Right. He notes that Horowitz’s brand of soul-searching was probably difficult for the demoralized left to take, especially given his combative, take-it-or-leave-it style. “I’m sure he made it very hard for people,” Oppenheimer said. “He had a very keen sense for where the left’s genuine hypocrisies and vulnerabilities were, but he hit it in this way that was blunt and unsympathetic and unforgiving.”

Collier said he and Horowitz share a “tragic vision,” informed by the idea that the right is on the losing side of history.

As vocal as he was about his misgivings, Horowitz might have remained on the left, but news of North Vietnamese re-education camps and the Khmer Rouge genocide in Cambodia pushed him over the edge. Unlike his comrades, Horowitz said he could no longer rationalize the crimes of his supposed ideological allies. In his memoir, Horowitz recalled airing his doubts to Berkeley alum and activist Michael Lerner ’67, Ph.D. ’72, who would eventually become a progressive rabbi. “Even to raise such questions,” Horowitz claimed Lerner replied, “is counter-revolutionary.” Horowitz grew more alienated and angrier by the day.

His epiphany came one day in the late 1970s, while browsing the aisles of Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue. The shelves held a kaleidoscopic selection of books, each one an expression of a distinct worldview. As a Marxist, Horowitz had always been confident that his ideology explained everything, that he possessed the esoteric wisdom that “provided the key to all other knowledge.” But now a heretical thought seized him: What if his theories were wrong? Not just wrong in a few details, but wholly, monstrously wrong?

“We thought we could dig a foundation under the doubt, and it wouldn’t mean a wholesale self-re-evaluation,” Collier said. “But the foundation kept slipping.”

BY THE MID-1980s, Horowitz was finally ready to come out as conservative. He voted for Reagan in 1984, and he and Collier wrote about it in The Washington Post the following year, attacking their old comrades for supporting Ho Chi Minh, Castro, and the Sandinistas. Voting for Reagan, they declared, was “a way of finally saying goodbye to all that.” In contrast to Reagan’s habitual sunniness, Horowitz’s worldview was dark. “The best intentions can lead to the worst results,” he wrote in The Village Voice in 1986. “I had believed in the left because of the good it had promised; I had learned to judge it by the evil it had done.”

Collier said he and Horowitz share a “tragic vision,” informed by the idea that the right is on the losing side of history. It sounds counter-intuitive, given the conservative movement’s victories over the last 50 years. But Collier means the battle for America’s soul. As he and Horowitz see it, the rise of political correctness has fractured America’s self-conception, replacing the country’s founding creed of “E pluribus unum” with a divisive system of groups defined by ethnicity, class, and gender. What’s more, Collier said, the left destroyed America’s sense of itself as a nation that, however imperfect, was capable of doing good in the world. “People like David and me feel that we and our country have lost everything—in terms of what it was, what it meant, and how it sees itself.”

Horowitz perfected a sort of rhetorical two-step: Call for substantive discussion on a hot-button issue, but couch that call in language guaranteed to provoke a fight.

Although he had switched sides, Horowitz was, and remains, a less-than-doctrinaire conservative. An agnostic Jew who shares none of the Christian right’s illiberality, Horowitz hasn’t gone in for gay bashing, and he was virtually alone on the right in speaking up for murdered Florida teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012. But Horowitz had certainly become a strident anti-leftist, the arch-enemy of his former self.

As a young radical, Horowitz had helped blow up the dam, and now he would spend the rest of his life trying to hold back the waters. It was, he wrote, “my way of atoning for what I had done.”

Embracing his new team with a convert’s zeal, he decided to “speak in the voice of the New Left—outraged, aggressive, and morally certain.” In practice this meant relentless, totalizing attacks on the left, painting, say, radical organizer Saul Alinsky and mainstream Democrats like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton with virtually the same brush. In his 2000 work The Art of Political War, which was endorsed by GOP consultant and “dirty tricks” practitioner Karl Rove, Horowitz asserted that hard-core leftists controlled the Democratic Party, and that Republicans were getting steamrolled because they were too polite. To win, he argued, the GOP must adopt the left’s knife-fighting tactics.

“Politics is war,” Horowitz wrote. “Don’t forget it.”

To help wage it, he and Collier established what is now called the David Horowitz Freedom Center, a foundation dedicated to promoting conservatives in Hollywood, combating leftist “indoctrination” on campus, and exposing communist fifth columns on Capitol Hill. It isn’t the kind of think tank that publishes policy papers; in the words of its website, it’s “a battle tank, geared to fight a war that many still don’t recognize.” The center brought in $4.8 million in contributions in 2016 (Horowitz, as CEO, made $569,756). It supports a constellation of projects from the opinion site Frontpage to Discover the Networks, a sort of intelligence dossier on “the left and its agendas” featuring unflattering profiles of bogeymen ranging from George Clooney to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

As a young radical, Horowitz had helped blow up the dam, and now he would spend the rest of his life trying to hold back the waters.

Over the years, Horowitz perfected a sort of rhetorical two-step: Call for substantive discussion on a hot-button issue, but couch that call in language guaranteed to provoke a fight. In 2001, he bought a full-page ad in 35 college newspapers titled “Ten Reasons Why Reparations for Slavery is a Bad Idea for Blacks—and Racist Too.” Noting the practical difficulties of determining payments, he also argued that African-Americans had already received reparations in the form of welfare and affirmative action, and that they should be grateful to America for freeing them. (The Daily Cal ran the ad but later apologized for being “an inadvertent vehicle for bigotry.”) Horowitz told the New York Times that the pushback he got from the ad surprised him. “These black students come in and say, ‘This hurts our feelings,’” he said. “Come on, an argument hurts your feelings? Fight back.”

After September 11, Horowitz focused his attention on jihadist terrorism, arguing that radical Islamists had infiltrated American universities and other institutions. He declared that Students for Justice in Palestine is “the leading pro-terrorist, pro-Nazi organization on American campuses.” At Cal, his foundation distributed posters featuring glowering caricatures of individual pro-Palestine Berkeley professors above the legend “#JEWHATRED.” Horowitz even indulged in the conspiracy theory that members of the Obama administration, including Hillary Clinton aide Huma Abedin, were secret Islamist agents.

He also waded into the immigration debate. “The politically correct but factually inaccurate term undocumented immigrant is a typical weapon in the war to transform America’s society and culture,” he wrote in 2017. He insists that “…invasion is the accurate term.” Last year, he offered a ferocious defense of the Trump administration’s child separation policy and of his protege, Stephen Miller, who is considered its architect. Speaking to The Guardian, Horowitz barked, “Here’s the issue: should America, like every other fucking country in the world, particularly Mexico, have borders? That’s the issue. And the Democrats have just demagogued it to make it anti-immigrant. It’s bullshit.”

Many see Horowitz’s over-the-top approach to politics as rank opportunism, an act void of conviction. “It’s good business,” acknowledged Sol Stern. “People get wound up and think, ‘Oh, I’m gonna save the republic by giving David Horowitz 35 bucks.’” But Stern doesn’t doubt his old comrade’s sincerity. Neither does Ron Radosh, another convert to the right who has known Horowitz since they were teenagers. “David has a Leninist mentality,” he said, citing the communist leader’s ruthless, party-line style. “You’re fighting for the truth and there’s only one path to take.”

Collier, who calls himself a “mortified” Trump supporter, said Horowitz’s position is carefully considered. Trump represents the last, best chance of advancing Horowitz’s causes.

Sincere or not, that path strikes others as both offensive and immoral. The civil rights group Southern Poverty Law Center labels Horowitz’s center a hate group and calls Horowitz himself “a driving force of the anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant and anti-black movements.” In response to such charges, Horowitz typically cites his history as a civil rights advocate. Sometimes he threatens to sue. Both Radosh and Collier scoffed at accusations of bigotry. “There’s been a lot of hit pieces: ‘David’s a racist, David’s an Islamophobe,’ all of that bullshit,” Collier said. “David is nothing like that.”

MOST PEOPLE WHO UNDERGO political conversions mellow as they settle into their new identities, according to Berkeley psychology professor Mendoza-Denton. Here again, Horowitz is atypical. If anything, his zeal has only intensified with the years.

He embraced Trump early, even as many on the right distanced themselves. And he has remained unflaggingly loyal ever since. In his 2017 bestseller, Big Agenda, Horowitz praised Trump’s “readiness to go for Democrats’ jugular.”

That support has caused a rift with some of his old left-to-right fellow travelers. In 2017, Stern published a column in the Daily Beast comparing Horowitz’s “hero worship” of Trump to his onetime infatuation with Huey Newton. Radosh, too, criticized Horowitz in a Daily Beast column, calling out Horowitz’s tweets demanding that Hillary Clinton be jailed, his suggestion that pipe bombs sent to Democrats and media figures were false-flag operations, and his support for Alabama senatorial candidate and alleged pedophile Roy Moore. When I talked to Radosh he said, “It’s a shame what happened to him.”

Collier, who calls himself a “mortified” Trump supporter, said Horowitz’s position is carefully considered. Trump represents the last, best chance of advancing Horowitz’s causes—or at least of slowing the left’s long march. “He’s less put off by the egregiousness of Trump than I am,” Collier said, then amended the statement. “He’s not at all put off by it.” Horowitz’s Trumpism, he said, is “the radical commitment of a radical mind.”

It’s been said that as we age our personalities are distilled to their essence. Perhaps that’s why Horowitz keeps fighting, the once-and-future redeemer compelled to spend his days in ceaseless struggle with his former self. Maybe it couldn’t be any other way. As Horowitz wrote in his autobiography, “There is no one to save us from who we are.”

Chris A. Smith is a magazine writer and college journalism and politics instructor in San Francisco. He writes regularly for California.

From the Spring 2019 issue of California.