Another Nobel season has come and gone, and for the second year in a row, Berkeley has won laurels. Economics Professor David Card and Berkeley-trained physiologist David Julius, Ph.D. ’84, won the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economics and in Physiology or Medicine, respectively.

Card’s win makes him Berkeley’s sixth Nobel-winning economist and its 22nd Nobel laureate (or its 27th, depending on whether you count those who arrived at Berkeley with their prizes in tow). Julius’s award officially accrues to UCSF, which now boasts six laureates.

The Nobel committee honored Card for his “empirical contributions to labor economics,” including work that challenged orthodox understanding of inequality and the various forces that impact low-wage workers. He shares the prize with MIT’s Joshua Angrist and Stanford’s Guido Imbens, who briefly taught at Berkeley as well.

Card conducted studies in the 1990s which showed that, contrary to expectations, increases in minimum wage didn’t cause significant job losses. His work on immigration also bucked conventional wisdom, demonstrating that immigrants did not adversely affect the opportunities of native-born workers.

When Card first heard he had won the award at his family’s home in Santa Rosa, he thought it was a prank.

“I have a couple of friends who would pull a stunt like that,” he told Berkeley News.

He also downplayed his achievement.

“Most old-fashioned economists are very theoretical, but these days, a large fraction of economics is really very nuts-and-bolts, looking at subjects like education or health, or at the effects of immigration or the effects of wage policies. These are really very, very simple things. So, my big contribution was to oversimplify the field,” Card said.

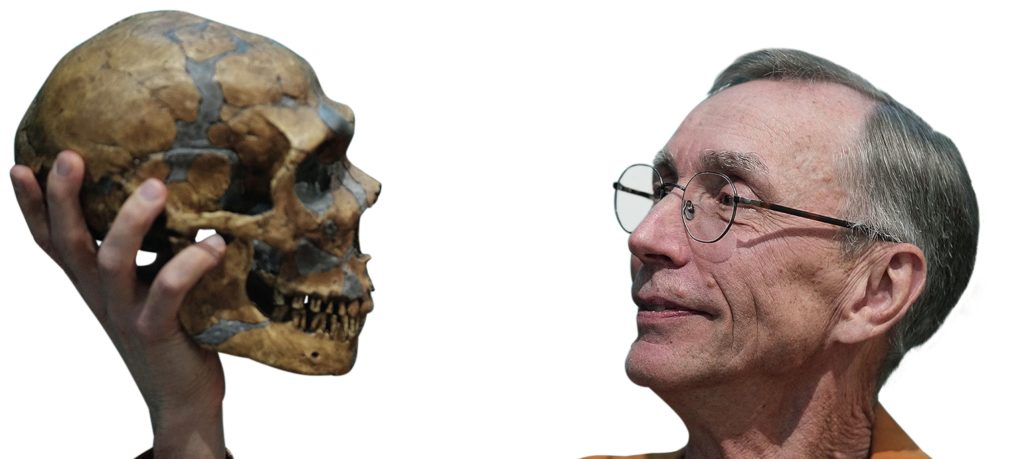

David Julius, a professor and chair of the Department of Physiology at UCSF, shared the prize in Physiology or Medicine with Scripps Research’s Ardem Patapoutian. The two researchers were recognized for their “discoveries of receptors for temperature and touch.”

At Berkeley from 1977 to 1984, Julius joined the labs of Jeremy Thorner and Randy Schekman (the latter a 2013 Nobel laureate in the same category), where he worked to make clear the mechanisms of peptide hormone processing and secretion in brewer’s yeast.

“David published an outstanding series of papers,” Schekman said of his former mentee. “This achievement was the first indication of David’s insight and technical excellence.”

During his postdoctoral studies at Columbia, Julius’s interest shifted to how external stimuli interact with human receptors. Unlike smell and sight, the workings of which were fairly well understood, pain and touch remained mysterious.

No sensory system matters more to survival than pain, Julius told the New York Times. So, he and his lab started investigating how human bodies detect painful temperatures and chemical irritants.

To do this, his lab at UCSF gathered a variety of noxious substances, including toxins in tarantulas and coral snakes, and capsaicin, the compound that produces the spicy heat in chili peppers.

By introducing different proteins from sensory neurons to cells that don’t normally respond to capsaicin, the group discovered a receptor called TRPV1 that is activated not only by hot peppers, but also by acid and temperatures greater than 110 degrees Fahrenheit. It also contributes to hypersensitivity to heat after tissue injury, such as experienced after a sunburn.

In addition to heat sensors, Julius and his team also discovered a channel called TRPM8 that responds to cold temperatures, and another, TRPA1, that responds to the punch in wasabi.

“David is a true original,” Schekman said of his former student and fellow Nobelist, adding that it was a “trait that he must have had at the very start, because I don’t think this can be taught. The product of his originality has led to revolutionary discoveries in how organisms perceive pain and changes in temperature.”