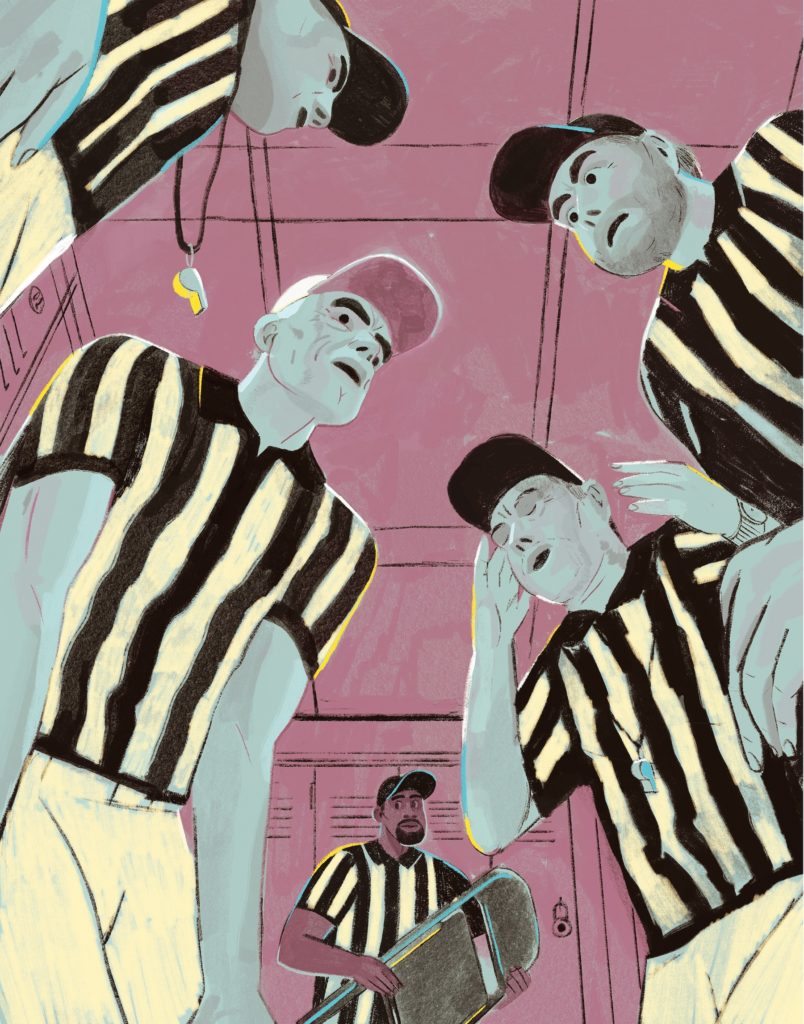

The pounding on the door sent a shudder through the tiny locker room.

Inside, six members of the Pacific-10 Conference officiating crew huddled, already on edge because of what had transpired just minutes earlier on the field at California Memorial Stadium.

Now their locker-room door trembled. These were not the polite knocks of the home attendants. This was the drumbeat of the aggrieved. As the clock neared 4:15 p.m. on November 20, 1982, the pounding on the door got louder.

The six officials had just awarded the California Golden Bears a 25–20 victory over archrival Stanford in the most outrageous finish in college football history, the mind-bending five-lateral improvisation that would come to be celebrated simply as “The Play.”

In giving Cal the winning touchdown, the six men in black and white may or may not have flouted the rules. Without doubt, they had helped violate the conventions of orderly competition. They had validated chaos. Permitted pandemonium. OK’d the unthinkable.

And now someone (actually, it sounded like a gang of someones) wanted to breach the sanctum where the officials had retreated from a field swarming with jubilant Golden Bear fans and the enraged followers of the Stanford Cardinal.

“We didn’t know who was trying to come in. It could have been anybody,” field judge Jim Fogltance would recall, half a lifetime later. “And we didn’t know how we were going to get out of there, either.”

One of Fogltance’s fellow officials, back judge Carver Shannon, a strapping former defensive back, prepared to defend himself and his comrades. Shannon grabbed a folding metal chair and held it like a shield.

Just before the door swung open, there was a pause, Fogltance recalled. “It was tense,” he said. “Very, very tense.”

Forty years on, many of the Stanford faithful are still pounding on a virtual locker-room door. The more voluble tend to drop an f-bomb and a pungent recrimination whenever the subject of The Play arises: “His knee was down!” they say. “That last lateral was forward,” they harrumph. (More on the knee and that lateral later.)

Even the most reticent shake their heads and mutter at any reminder of how Cal won a game it surely had lost, denying Stanford and its glorious quarterback, John Elway, their just rewards: Certainly, a bowl game for the team. And for Elway, perhaps, the Heisman Trophy.

Hey, Stanford fans, in case it wasn’t clear all these years: We denizens of the far side of San Francisco Bay get it! We (kind of) empathize with your pain! We really do. Because the agony of defeat is the birthright of any fan of Cal football.

We are the followers of a team that, for most of the 40 years since The Play, has engineered ingenious new ways to disappoint. We hail from a great academic university, to be sure, but one that hasn’t been to the Rose Bowl game since 1959 and hasn’t won the Pasadena classic since Franklin D. Roosevelt was in the White House. Regret and self-loathing (leavened with occasional wonder and joy) are as native as oak trees on “our rugged eastern foothills” (as the fight song has it).

The fate of games lay solely in the hands of the six men in black and white stripes. Their decisions, usually rendered in seconds, were as final as a life sentence.

We recognize athletic anguish, sons and daughters of Palo Alto. Actually, we kind of feel like we invented it; we who sat in the student section on the east side of Memorial Stadium on that afternoon long ago.

Yes, we saw the same things you saw. We saw four of our Golden Bears run over your Cardinal football team and outflank your silly, outrageous marching band to record the greatest touchdown in college football history. And we also saw the things we never dare concede in loud, performative bull sessions with you TreePeople.

We saw Cal running back Dwight Garner squashed under a pile of Stanford players and acknowledge the powerful, magical thinking we must invoke to insist Garner couldn’t possibly have been down.

We saw Cal’s Mariet Ford heave the final, miracle lateral backward, only to have the ball somehow float (illegally?) upfield and into the waiting embrace of Kevin Moen, before his final strides into immortality.

We saw how the six officials huddled amid the tumult and how it took less time than it takes to order a pizza for them to pass judgment on the most nonsensical, confounding play any of them would ever witness.

At the risk of surrendering my hard-earned Cal Fanatic card, I concede it here and now: The 85th Big Game righteously could have, maybe should have, finished with the penultimate play, a Mark Harmon field goal capping a heart-stopping 20–19 Stanford victory.

But it didn’t. And so four seconds turned into an eternity. And so sorcery ensued. And, so, the NCAA record book confirms it: Cal 25, Stanford 20.

But WHY? Why would august entities like the Pacific-10 Conference and the National Collegiate Athletic Association sanctify a football game that ended with roughly 170 outside agitators mucking up the field of play?

Well, because college football games in 1982 were still gloriously freewheeling and untidy affairs. Many games did not appear on live TV. None of the plays had to be subjected to instant video analysis and adjudication by some unseen, faraway Voice of Authority.

The fate of games lay solely in the hands of the six men in black and white stripes. Their decisions, usually rendered in seconds, were as final as a life sentence. Without possibility of reprieve. Without redress. Without respite from a potential lifetime of haunting memories.

I tracked down three of the surviving four officials who called the game that fall afternoon to learn what made them give the seal of approval to The Play. One was certain the call had been right. A second saw no reason to revisit the issue. The third was sure he wasn’t sure.

All three agreed that the ultimate credit, or onus, for their ruling belonged to the head referee and their crew chief, the late Charles Moffett. I would learn a fair amount about Charlie Moffett and the sway he held over his fellow officials and over that game.

I would come to believe that Moffett, an official acclaimed for his cool head and fairness, also harbored a secret prejudice… against his own power. He had his own sense of order, his own athletic history and—upon further review, as the officials like to say—his own reasons for letting disorder be the order of the day.

Officials typically operate in anonymity. But within their own community, they have their own leaders, role models, and even hall-of-famers. Charlie Moffett was all that, a true leader in his field.

He had refereed not only football but basketball in the Pac-10 for about two decades, a rare multisport authority in an era of increasing specialization. At off-season clinics, he schooled football officials on the rules, on proper positioning, and on how to maintain control of a game.

Moffett had gained a reputation as a cool arbiter, always calm, fair, and in command, but with a light touch.

“Charlie was the type of guy who could step on your shoe without scuffing it,” Fogltance said. His crewmates figured the white hat, always worn by the referee, suited him just right.

On one point of officiating wisdom, Moffett was adamant: Don’t throw a penalty flag unless you are absolutely certain there has been an infraction.

“Charlie constantly said, ‘Don’t assume a darned thing. You never know when things are going to change, so better to see how it unfolds and what happens. Don’t anticipate a call,’’’ umpire Walter Wolf, another member of the 1982 Big Game crew, remembered, years later. “That was something that I always carried with me.”

Linesman Gordon Riese learned the same lesson. When Riese became a referee himself, he introduced his crews to the Moffett Doctrine: The best football officials stay in the background. They let the players play the game and intercede only when the rules demand it.

But what gave birth to Moffett’s philosophy? With the power to mete out instant justice, why had he modeled restraint? Apparently, no one had asked the old referee those questions before he died in 2002, at age 76.

So I went looking for clues. I spoke to his contemporaries and pored over snippets on the internet. But nothing offered an inkling about why Moffett embraced a kind of judicial laissez faire. I was ready to stop trying when I stumbled over something unexpected.

Like a lot of people bound for a life as athletic officials, Moffett grew up an athlete himself. At Peabody High School, in a small Kansas town, the future ref starred in football, baseball, and basketball. Graduating in 1943, he was drafted into the Army and headed to Fort Leavenworth for basic training. But sweeping the barracks one day, he struggled to catch his breath. Asthma. The Army doctors examined Moffett and declared him 4F, unfit for military service.

That redirected teenaged Charlie to the University of Kansas, a couple of hours northeast of his hometown. With so many young men at war in the Pacific and Europe, coaches on the Lawrence campus struggled to fill their rosters. A newsletter for Jayhawk fans noted that the coaches were thrilled to greet Charlie Moffett, “a sterling all-round athlete.”

In his freshman year, Moffett made an immediate impact. By his sophomore year, in 1944, tailback Moffett was one of the Jayhawks’ top offensive players, scoring several touchdowns.

But it’s the touchdown that got away that had to have been as memorable as any that young Moffett scored. The occasion was Kansas State’s homecoming game against rival Kansas. The Wildcats held on to an 18–14 lead over Moffett’s Kansas team as the final seconds of the game ticked away.

I would never have learned the details, except that someone put the Kansas State Collegian, the college newspaper for the Jayhawks’ archrival, on microfilm. More importantly, they made the long columns of text search-friendly, disgorging the name “Moffett.” The details of the big rivalry game sprang to life, right on those graying pages.

“Charlie constantly said, ‘Don’t assume a darned thing. You never know when things are going to change, so better to see how it unfolds and what happens. Don’t anticipate a call.’”

Walter wolf

The game came down to the final moments. Then this: “Wildcats, past and present, felt their hearts sink when Charles Moffett of KU, with seconds to go before the final gun, made an 80-yard straight off-tackle run to fall exhausted across the goal line,” the Collegian reported. Moffett had faked a pass before sprinting down the sideline, untouched, for the score.

The kid from little Peabody had given his team a miracle victory, and on the final play of the game! What a bonanza! (As an announcer 1,000 miles west might one day say.)

But the game officials thought otherwise. They flagged one of Moffett’s Kansas teammates for an illegal block in the back—clipping—though it was 15 yards behind the play and Moffett was closing in on the end zone. “The clipping foul … was one of those all-too-frequent rule violations that come in the heat of strife but have no direct part in the play,” the Collegian reported. Regardless, the zebras waved off the touchdown.

The game had seemed so over that one official had left and had to be called back on the field for one final play. Fans crowded the sidelines for Kansas’s last gasp. One of Moffett’s Kansas teammates caught a pass, but could advance it only to midfield. Game over.

Moffett’s improbable run to victory had been erased. Kansas had lost. In the biggest game of his young life, the officials had stolen away Charlie Moffett’s glory with a penalty flag.

Years later, Moffett moved west to Seattle to advance his aerospace career. He never mentioned his college heartbreak to his fellow football officials, but it must have lingered. How could it not? Is it too much of a leap to imagine that the victim would carry an abiding sense that officials should know their place?

We will never know for sure. But we do know that on November 20, 1982, Moffett’s crew at Memorial Stadium fully embraced the Moffett Doctrine. As much as Richard Rodgers’s smarts and Kevin Moen’s resilience, that imperative created one of college football’s truly transcendent moments.

No one could have known any of that on the late afternoon of November 20, 1982. As the sun swooned toward the Golden Gate, shadows lengthened across the floor of Memorial Stadium. Fans on both sides already knew they were witnessing one of the greatest sporting events they had ever seen. Even Cal fans might sourly concede that the universe seemed in balance; with the best college player in the country, Elway, on his way to victory and the star-crossed Bears on their way to another painful loss.

The south end of the stadium, overflowing with red-and-white Stanfordites, rocked in celebration. Members of the Stanford Band had left their seats to stand just behind the end zone, preparing for their post-game concert. Euphoric, they blasted “All Right Now,” seemingly louder than they had ever blasted it before.

With four seconds left and California trailing by a single point, the officials readied for what should have been Cal’s last gasp. It seemed so pro forma; a desperate kickoff return that would be snuffed out, so the Festivus Palo Altus could begin in earnest.

The Bears lined up for the final kickoff with only ten men on the field. Moffett & Co. failed to notice, or correct, Cal’s infraction: The Bears had only four players lined up between the Stanford 35- and 40-yard lines, but the rules said five players should have been there. (Note: Stanford had been penalized 15 yards for excessive celebration after Harmon’s field goal.)

But many things were out of whack at that moment: The Golden Bears had deployed their “hands” team of players known for their ball-handling skills. They would be ready to field an anticipated short kick from Stanford. A couple of members of the kickoff return squad, though, had become lost in a fog of despair and didn’t take their places. Coaches belatedly pushed one substitute onto the field, leaving Cal still one player short.

And those who took the field weren’t all where they were supposed to be. Kevin Moen, a fearsome hitter as a safety, was on the hands team because of his history as a high school option quarterback. He had the dexterity and quick reactions for the assignment. Seeing the kick squad short a man, Moen faded back to a position about 15 yards behind the first row of Cal players. It was a position that no one had previously contemplated. As Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite (himself an “Old Blue”) would write: “It was one of those inspired decisions by which history is altered and football games are won.”

Harmon approached the ball and dribbled it forward. But instead of a difficult, odd-hopper, his kick bounded almost magically to the non-position Moen had filled. Moen grabbed the ball, took a few strides and pivoted left, throwing an overhand pass to fellow defensive back Richard Rodgers. Quickly hemmed in along the sideline, Rodgers shoveled the ball back to Dwight Garner, a running back.

Five Stanford tacklers surrounded and swarmed over Garner. As the Cal freshman crumpled to the turf, his right knee dropped precariously close to the turf. But in the post-game locker room (and every bar and golf course where he would encounter Stanfordians for the next four decades), Garner remained steadfast: “I was not down.”

Closest to the play was Jack Langley, the head linesman. He would later declare that Garner’s forward progress had not been stopped. Wolf, the umpire and a big, blustery former college rugby player, also had a view of Garner’s predicament.

“Looking at the film later I thought, ‘Gosh sakes, I’m glad I didn’t blow my whistle,’” Wolf said.

Wolf made a habit of avoiding regrets.

“People always ask me if I ever made a bad call in my career,” Wolf said, “and I say, ‘I can’t remember a bad call I ever made because I obviously always felt it was the right call at the time I made it.’”

Seeing Garner hit the turf, at least three or four Stanford players—convinced the game was over—sprinted off the sideline and onto the field to celebrate. They ran right past line judge Riese. Then, seeing the ball still alive, they pivoted and sprinted back toward their sideline. Riese threw a flag for too many men on the field.

But The Play continued. Garner managed to squirt the pigskin backward. Rodgers grabbed it out of the air and swung toward the middle of the field. With Stanford defenders again closing in, Rodgers flipped the ball to Mariet Ford, arguably Cal’s fastest player, who finally broke free of the red and white horde.

Though Cal’s first three laterallers ran mostly, er, laterally, Ford turned sharply south toward the Stanford end zone. He sped across the 30-yard line. But three Stanford tacklers, including kicker Harmon, boxed him in. Again, The Play appeared to be over.

But Ford threw himself at the men in white, taking out all three would-be tacklers while simultaneously heaving the ball backward over his right shoulder. It was the single most extraordinary in a series of extraordinary tosses.

Riese, still frozen along the Stanford sideline, was the closest official to the final lateral. Decades after the event, he was not nearly as sanguine as Wolf about the outcome, or his role in it.

Meeting at his home in suburban Portland, Oregon, to discuss that moment, Riese came to the door carrying a photograph. It showed the Memorial Stadium field crammed with a crazy quilt of players from Cal and Stanford, roughly 140 members of the Stanford band, and a few miscellaneous fans, including two members of the Stanford Rally Committee carrying the Axe, the Big Game’s hallowed trophy.

This was a rare still image of The Play, taken from the Stanford end zone. It captured the moment Ford’s toss to Moen hung in the air. Among the picture’s revelations: a clear image of one of the officials with his arms spread wide like a bird… as if waving the play dead? (None of the officials on the field ever acknowledged—publicly at least—making such a signal.)

Riese focused not on his colleague but on himself, positioned near the Stanford sideline. “Look at me. I’m nine or ten yards behind the ball, out of position,” he said, several decades seemingly failing to dull his chagrin at his perceived failure. “At least nine yards out of position.”

Under normal circumstances, a line judge like Riese would have followed the ball down the field. But the photo confirmed that the field was anything but normal, with the riot of noncombatants clogging the artificial turf, convinced the game was over.

Riese remembers worrying that the Ford-to-Moen lateral had traveled forward. He had a vague recollection of reaching toward his back pocket for a yellow penalty flag. But the youngest of the officiating crew also recalled Moffett’s admonition: “Don’t get involved unless you’re absolutely sure,” Riese said. “Don’t guess.”

“People always ask me if I ever made a bad call in my career, and I say, ‘I can’t remember a bad call I ever made because I obviously always felt it was the right call at the time I made it.’”

walter wolf

Riese was out of position. He was not sure. He didn’t guess. He left the yellow flag in his pocket, as Moen took the Ford lateral and thundered 25 yards—past befuddled band members, past a few last stumbling Stanford players, past the Axe, mounted on its wooden plaque, past the world as he had known it and into college football lore.

Moen raced across the goal line and, bringing the ball overhead, took one final leap. Fate, and a bit of playful retribution, demanded that Moen land squarely on Gary Tyrrell, a Stanford trombone player who had wandered into the end zone, well behind most of his bandmates. Prematurely ecstatic.

“He’s gonna go into the end zone!” Cal and KGO-AM radio man Joe Starkey shrieked in delight. Cal teammates swarmed over Moen. But Moffett and his crew had not yet validated the touchdown. They huddled near the Stanford sideline amid bedlam and then a queasy silence, as 75,662 fans awaited the verdict.

A player or two, including Cal punter Mike Ahr, stood just outside the ref’s circle on the western sideline, close enough to hear the deliberations. So did one fan who, amazingly, was able to lean right into the officials’ scrum.

Moffett, ever in command, took control of the sideline huddle. “I asked if anyone had blown a whistle during the return. No one had. I asked if every one of those laterals was clearly backward. They said they were,” the referee told Sports Illustrated when the magazine published its one-year retrospective on The Play.

“Well then, I said, ‘We have a touchdown,’” Moffett recalled. “I threw my hands in the air to signify as much. And it was like starting World War III.”

The Cal cannon sounded from the wooded hillside over Strawberry Canyon. Starkey launched into his epic paroxysm: “Oh, my God! The most amazing, sensational, dramatic, heartrending, exciting, thrilling finish in the history of college football!!” Cal students began to flow, like animated lava, onto the Pompeii of the stadium floor.

“Charlie always taught us, ‘If you’re not 100 percent sure, don’t throw the flag.’ And so, I just went by his wisdom.”

gordon riese

But Moffett, punctilious even in a crisis, was not ready to leave the field. He told his fellow officials that the Bears still needed to kick their extra point.

“There’s no way we are going to be able to clear the field,” Fogltance insisted.

“No, they don’t, Charlie,” chimed in Wolf. “We are out of here!”

With the mob on the field growing by the moment, Moffett demurred: “You’re right, let’s go.”

The officials took off their caps and the lanyards that secured the whistles around their necks, so they wouldn’t be choked by marauding souvenir hunters. They began running for the tunnel at the north end of the stadium.

It wasn’t long after they had reached the seeming security of the locker room that the pounding on the door began. When it burst open, it was not the angry fans or players the officials had feared. It was the even angrier Stanford athletic director, Andy Geiger, head coach Paul Wiggin, and several Stanford assistants.

Talking fast and spiraling from loud to louder, the Stanford delegation insisted on an explanation, questioned the officials’ sanity, and demanded they be allowed to redo the final play. (Back in the Stanford locker room, coaches had told their players to keep their uniforms on, until the dispute had been resolved.)

The normally pacific Wiggin, once an All-American lineman at Stanford, unleashed the plainest string of expletives he could muster. (He told me that he was in a “rage state,” adding: “What you saw from me was just sheer anger and probably a lot of stupidity.”) Umpire Wolf would remember a blood vessel dancing on the Stanford coach’s forehead. One bystander recalled that a member of the Stanford crew barked: “This is going to cost people their livelihoods!”

The diatribe was so heated that Cal’s athletic director, Dave Maggard, a former Olympic shot putter, who had been about to enter the room, thought better of it.

“I decided I had better leave well enough alone,” said Maggard. He waited out the storm in a hallway.

“I couldn’t believe this was happening,” said Riese, who was then in what amounted to his third full year officiating college football games. “I couldn’t believe anyone was in our dressing room after the game. You just sat there and thought, ‘What just really happened? And where is this going?’”

Moffett calmly explained that there had been no penalties against Cal. And, in any event, there was no provision to order the teams back to the field for a do-over.

Stanford offensive coordinator Jim Fassel, a future NFL head coach, shook his head in disgust. “They are not going to change their minds. Let’s get out of here,” Fassel said, according to John McCasey, the Cal sports information director who witnessed the showdown.

The Stanford coaches charged out, though their angry exit—meant to convey their utter disdain for the wrong-headed refs—instead took a mock-comic turn. The coaches had taken the wrong door. Suddenly, the furious losers found themselves on a balcony, looking outside the stadium. They were forced to make a Keystone Kops–style about-face, back through the officials’ locker room, before they could make their final escape into the justice-less Berkeley afternoon.

Later that evening, the officials regrouped at their hotel in the Berkeley marina. By then, they had a chance to see the television replays and to fully comprehend the audacity of Cal’s final charge. Though most of the crew was at peace with the call they had made, Riese continued to fret.

“I always prided myself on being in the right place at the right time, but I didn’t have a great opportunity to be where I was supposed to be at that time,” Riese said. “I didn’t feel very good about what happened.”

Moffett consoled him, saying that the lone TV camera focused on the kick return offered inconclusive evidence. “He said, ‘You just can’t tell from what we’re seeing’ on the replay,” Riese recalled. “And, like I said, Charlie always taught us, ‘If you’re not 100 percent sure, don’t throw the flag.’”

“And so,” Riese said, pausing for a good while, “I just went by his wisdom.”

The next day, Fogltance boarded a plane in Oakland for the flight home to Arizona. Seated next to him, a woman in Stanford cardinal read the sports section.

“Did you see the Big Game yesterday?” she said. Still frazzled, Fogltance had no stomach for a confrontation. “No, what happened?” he responded.

“Those refs really screwed us over,” the woman snapped. “They gave the game to Cal.”

“Yeah,” said the anonymous field judge, smiling ruefully and settling into his seat. “That’s what the refs will do to you, every time.”

James Rainey ’81 is a longtime staff writer at the Los Angeles Times and former sports editor at the Daily Californian, as well as an eyewitness to The Play. He asks that readers who enjoyed this story consider a donation in any amount (givebutter.com/w68cQv) to support the 150-year-old campus newspaper.

…

California magazine is an editorially independent non-profit magazine. We need your support to keep producing award-winning journalism about the world of Berkeley and Berkeley in the world. Please consider a donation in any amount. Fiat Lux and Go Bears!