I was 66. It was 2018, and a friend of mine said she had done 23andMe. So I thought oh, what the hell.

Weeks later, my results popped up on my computer. The first thing I learn is that I’m 50 percent Ashkenazi Jewish. I was raised completely not Jewish, but I had always felt some kind of strange mystical connection to Judaism. It started when I was 9 years old, after I read Anne Frank’s diary. I would have dreams about trains and gray landscapes with these harrowed faces in the window and was convinced I must have been Jewish in a past life.

My first reaction was to scream out loud—it was so exciting. I felt so affirmed. The second thing I did was text my five brothers and sisters—I’m the eldest of six. I told them, “I knew it. I knew we were Jewish.” That euphoria lasted until my adult son said, “Mom, if you’re 50 percent Jewish, that means one of your parents had to be 100 percent Jewish.” Math was never my strong suit.

I asked my siblings to take a DNA test, too. I was on tenterhooks waiting for those results, and it turned out, they were only my half-siblings, all five of them. I had a different father than the rest of them. Suddenly, I went from having five brothers and sisters to five half-brothers and -sisters. So at that point, my euphoria turned into grief.

I knew that my mother was pregnant when she married the father who raised me, and clearly she was pregnant with someone else’s child. I also knew that she was engaged before, and she always talked about him.

Armed with his name and my journalism degree, I started researching him. Sadly, what I found first was his obituary. My mother and father had also died. I had no one to ask about it. That was a big feeling of frustration for me. But, I tracked down his children, and they graciously agreed to do a DNA test. Sure enough, we were half-siblings. It was confirmed, Norman Peterzell was my biological father. My new sister said, “The minute I saw your picture, I knew. You are like a twin of our father.”

It turned out, Norman had stayed in touch with my mother her whole life. He had written a eulogy for her. There was a copy of it in his papers. The way he described her was to a tee, and very loving. And I think she was the love of his life. I don’t think he knew that I was his daughter. I don’t think the father who raised me knew I wasn’t. But I’ll never know.

I was always completely different than my younger siblings. They’re all Amazons, and very sporty. I was short and bookish. It turned out my “first” father or “true” father loved to write. He loved fine food and culture, and he had a good sense of humor.

Before journalism school, I worked in theater, then eventually started a book production company, editing and ghostwriting many, many books. That was later, during the intense child-rearing years, so I had no bandwidth to write for myself. My poetry was on the back burner. Then, suddenly, I was in my sixties and thought, “Man, you have to get serious,” so I started writing what would become my own book of poetry.

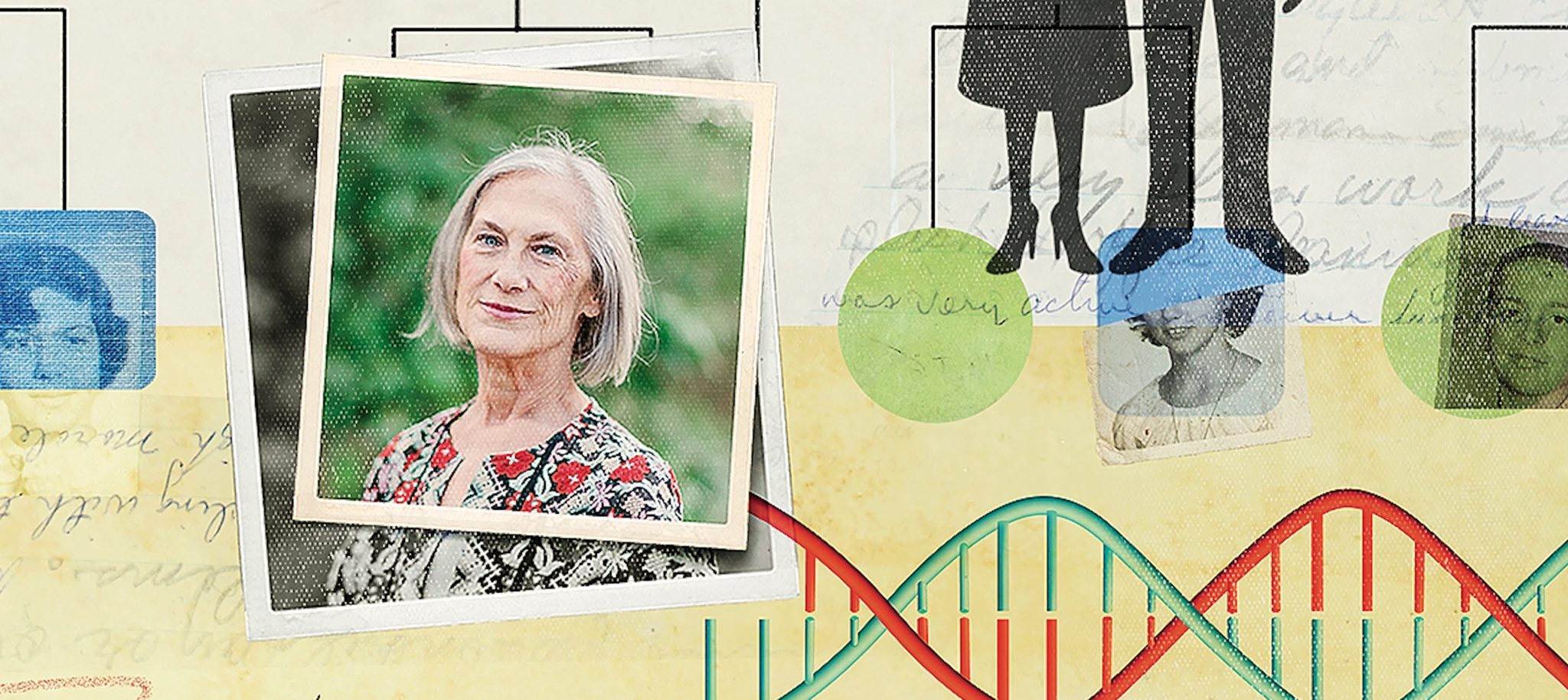

As I tried to start processing my unexpected parentage, I fell back on the way I always process my life, which is writing poetry. If I had found this out when I was in my twenties, I think it would have been devastating. Finding out in your sixties, your sense of identity is already pretty solidified. But it was still dramatic trying to integrate the two sides of my identity: the Jewish part and this new father with the family I’d grown up with. That’s why the book is called Double Helix; it’s about exploring the relationships with my first father, my second father, and my mother—and perhaps the relationship between the three of them.

I’m lucky my new family gave me a lot of photographs of Norman, so at least I know what he looked like. But the hardest part is I couldn’t touch my father. I couldn’t smell him. I couldn’t physically be with him. That longing will never go away.

Robin Dellabough ’75, M.J. ’81, is a former editor at California Monthly, predecessor to this magazine, and worked at UC Press and University Press Books. Her book Double Helix will be published on May 27 and is available for preorder at Finishing Line Press.