Writer Joan Didion, who graduated from Berkeley in 1956, died on December 23, 2021, at age 87. She will be remembered as one of the most distinctive voices not only of her generation but in all of American letters.

An accomplished novelist, screenwriter, and memoirist, Didion made her name primarily as an essayist, particularly with her early collections Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The White Album, each a heady cocktail of bracing social commentary and 100-proof prose. Her subject in those early works was the atomization of society—particularly in California, her native state. (Didion was a fifth-generation Californian, descendant of overlanders who broke from the Donner Party before it tried to cross the Sierra.) She showed us 5-year-olds high on acid in the Haight-Ashbury, the paranoia surging out of Topanga Canyon after the Manson murders, and horses catching fire in Malibu.

As a reader of Life magazine once observed in a letter to the editor, she wasn’t exactly Little Mary Sunshine, was she? Far from it; Didion fairly vibrated with dread. Who else could find fear and loathing in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” the verses of which she called the most terrifying she knew? To her, “life is but a dream” was a zombie’s credo.

She returned to prominence later in life with the success of her 2005 memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, about the death of her husband, John Gregory Dunne, and the serious illness of their daughter, Quintana. That book won her a National Book Award. But all along she had been a writer’s writer. So great was her influence on her trade that news of her death seemed to launch a thousand essays, as scribe after scribe confessed their indebtedness to the Didion style. And what a style it was: deceptively simple, musical, and mesmerizing. In his preface to her nonfiction collection We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live, literary critic John Leonard wrote, “I have been trying forever to figure out why her sentences are better than mine or yours … something about cadence.”

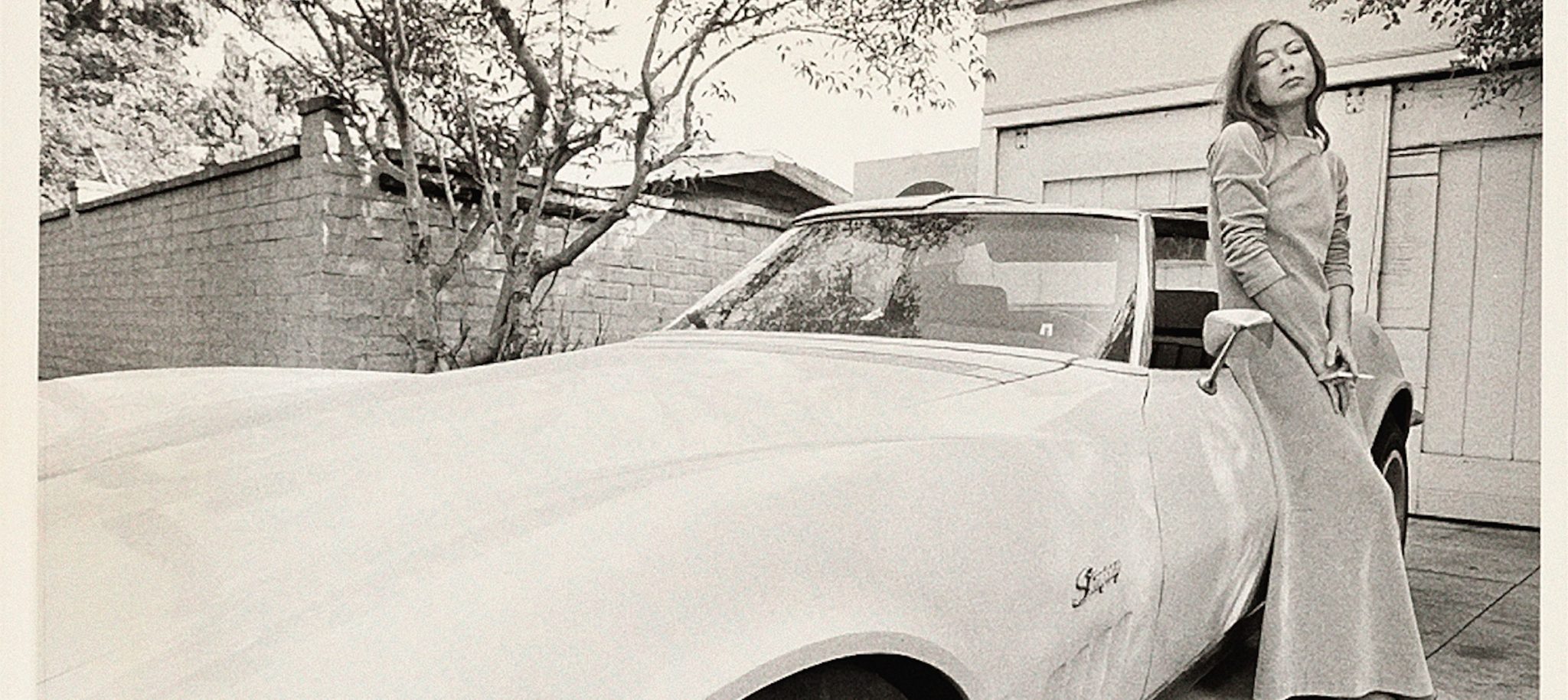

She had style off the page as well—one all her own. No literary personage ever cut a cooler figure than young Didion posing against her yellow Stingray, cigarette smoldering in her long, delicate fingers. Lithe and languorous in a sleek dress, with lines to match the Corvette’s, she was the very picture of badass femininity.

Didion’s essays were usually grounded in reportage, and she is often grouped with the New Journalists of her era. In truth, she had little in common with more flamboyant peers like Hunter S. Thompson, Tom Wolfe, and Norman Mailer—giant egos all, and men, of course. For her part, Didion could be imperious, but she didn’t swagger. She once wrote that her only advantage as a reporter was that she was “so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.”

It was true: For all her self-professed diffidence and seeming frailty, she wielded her pen like a musketeer wields a rapier.

Like her contemporary Janet Malcolm, who also died last year, Didion saw what she did for a living as an “aggressive, even a hostile act.” To write, she argued, was to grab a reader by the collar and say, “Listen to me, see it my way, change your mind.” Deny it all you want, “there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer’s sensibility on the reader’s most private space.”

She was proud of her Sacramento roots, and of Berkeley. Named the Cal Alumni Association’s Alumnus of the Year in 1980, Didion once called the University of California the state’s “highest, most articulate idea of itself”—itself a very Didionesque thing to say. After Cal, she went to New York, where she cut her teeth as a caption writer at Vogue. She came back to her alma mater nearly 20 years later, in 1975, as a celebrity author enjoying the kind of stardom more commonly afforded to Hollywood actors and rock stars. At the Regents’ Lecture that year, she delivered an essay to a standing-room audience. It was called “Why I Write,” and it is included in her most recent collection, Let Me Tell You What I Mean—the last book published before her death. In it, she confessed to feeling herself a fraud as a student at Berkeley, an impostor in the world of ideas. “During those years I was traveling on what I knew to be a very shaky passport, forged papers … ”

But that was the secret to her transformation. “Had my credentials been in order I would never have become a writer. Had I been blessed with even limited access to my own mind there would have been no reason to write. I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”

She spent her life doing just that, exploring the world and spelunking in the recesses of her own mind, then reporting what she found there. In very many cases, the results changed what we thought and how we thought and, certainly, how we wrote. Above all, she made herself heard. She told us what she meant. She did not go gently down the stream.