In February, Berkeley was dealt a major legal blow over one of the most promising technologies to come out of the university. The tribunal of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) ruled that the rights for CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing in human and plant cells belong to the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, not to Berkeley, potentially ending a years-long battle between the academic institutions.

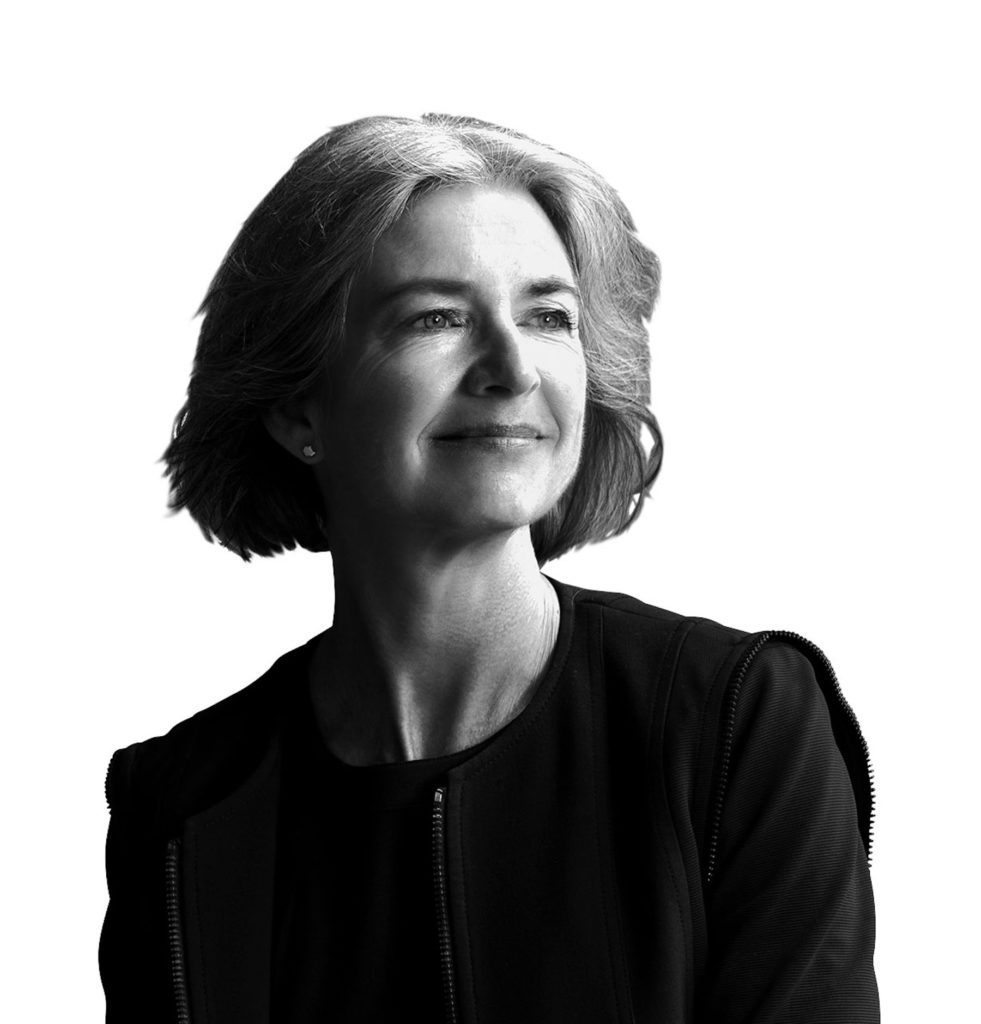

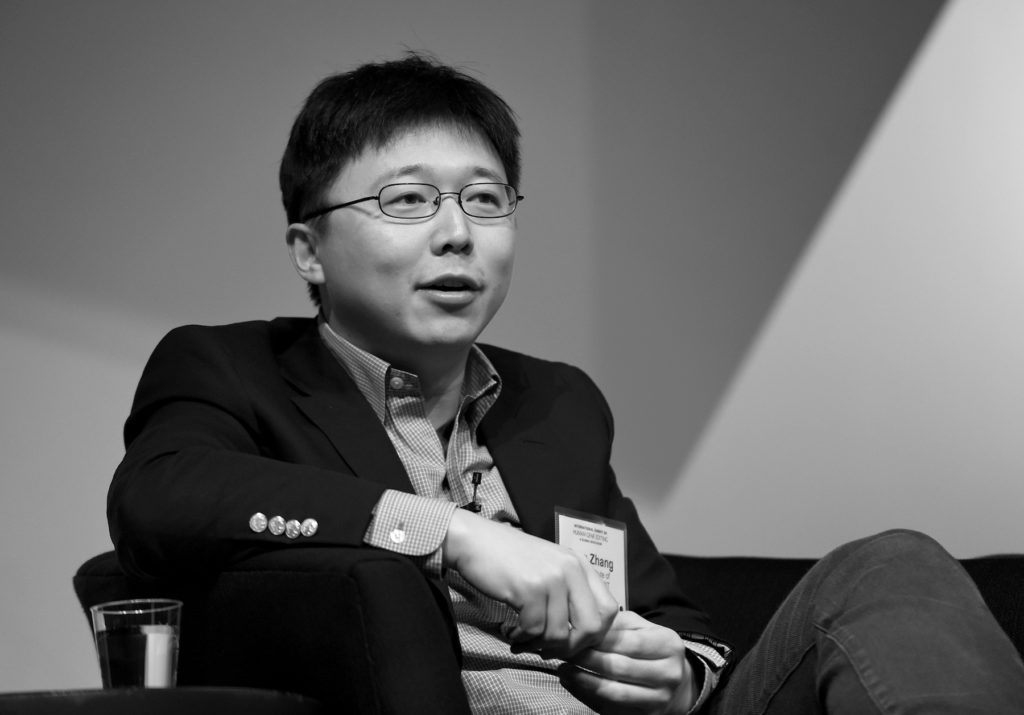

Berkeley scientist Jennifer Doudna won the Nobel Prize in 2020 for co-developing CRISPR-Cas9—a technology that enables researchers to manipulate and modify DNA with incredible precision. Doudna and her colleagues first disclosed their work in 2012, when they published a paper showing how CRISPR-Cas9 worked on DNA in a test tube. Shortly after, in January 2013, Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute published a paper detailing the successful adaptation of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome editing in eukaryotic cells—cells that contain nuclei—for human application.

Both institutions rushed to file patents, kicking off the long legal fight for the intellectual property rights to CRISPR-Cas9. While Berkeley’s initial patent application involved using CRISPR-Cas9 in all types of cells, the Broad Institute’s application pertained to the use of CRISPR-Cas9 specifically in plant and animal cells. The question was whether one side’s claims made the other’s invalid by default.

In 2014, the USPTO granted the Broad Institute its patent, a decision that Berkeley challenged. In 2017, the USPTO tribunal ruled that the institutions’ claims were independent enough from each other to both be valid, with the Broad Institute retaining rights in utilizing CRISPR-Cas9 in human and plant cells—the technology’s most lucrative application.

The tribunal reopened the case years later after Berkeley filed for patents on the use of CRISPR-Cas9 in eukaryotic cells. The decision came down to which institution was the first to invent the human-applicative technology. In February 2022, the tribunal officially ruled that Berkeley failed to provide concrete evidence of successfully using CRISPR-Cas9 in animal and plant cells before the Broad Institute. As a result, the additional patent applications Berkeley filed were not granted.

According to legal experts, the impact of such a decision could be devastating for Berkeley. Although it retains rights for uses in prokaryotes, like bacteria, the ruling may end up costing the University of California hundreds of millions of dollars in U.S. licensing revenue as companies all over the world begin to commercialize the groundbreaking biotechnology for human therapies.

The fight is not over. “The University of California is disappointed by the [tribunal]’s decision and believes the [tribunal] made a number of errors,” a university press release read, adding that the relevant parties are “considering various options to challenge this decision.”Doudna shared the same sentiments in a statement to the Wall Street Journal. “I am not pleased with the ruling. I don’t agree with it. It will be appealed,” adding, “I stand by our work. It is very clear in the scientific community what was done by whom and when.”