Each afternoon when the lunch bell rang at Maybeck High School, 16-year-old Gabriel Lautaro, aspiring DJ, would walk the two blocks to Telegraph Avenue and hit the record stores. The year was 1990, back when DJing meant two turntables and a crate of vinyl.

“Every day, I would spend half my lunchtime just digging for records,” he says. “And then after school? Digging for records.”

Lautaro was a member of that eclectic assemblage of vinyl geeks, collectors, and DJs known as “crate diggers” who spend significant portions of their lives combing through endless rows of vinyl for phonographic gems. For Lautaro, that could mean a rare Jamaican dancehall single or classic hip-hop track guaranteed to move bodies. His favorite excavation sites included Leopold’s for new but obscure stuff, and both Rasputin locations—the big store for new vinyl (“buzzing fluorescent lights and funky beige carpets”), the smaller one across the street for used (“Madness. Mountains of shit to look through”)—and the then newly opened Amoeba Music.

“It was like a frickin’ mecca for me,” he says. “I was in paradise.”

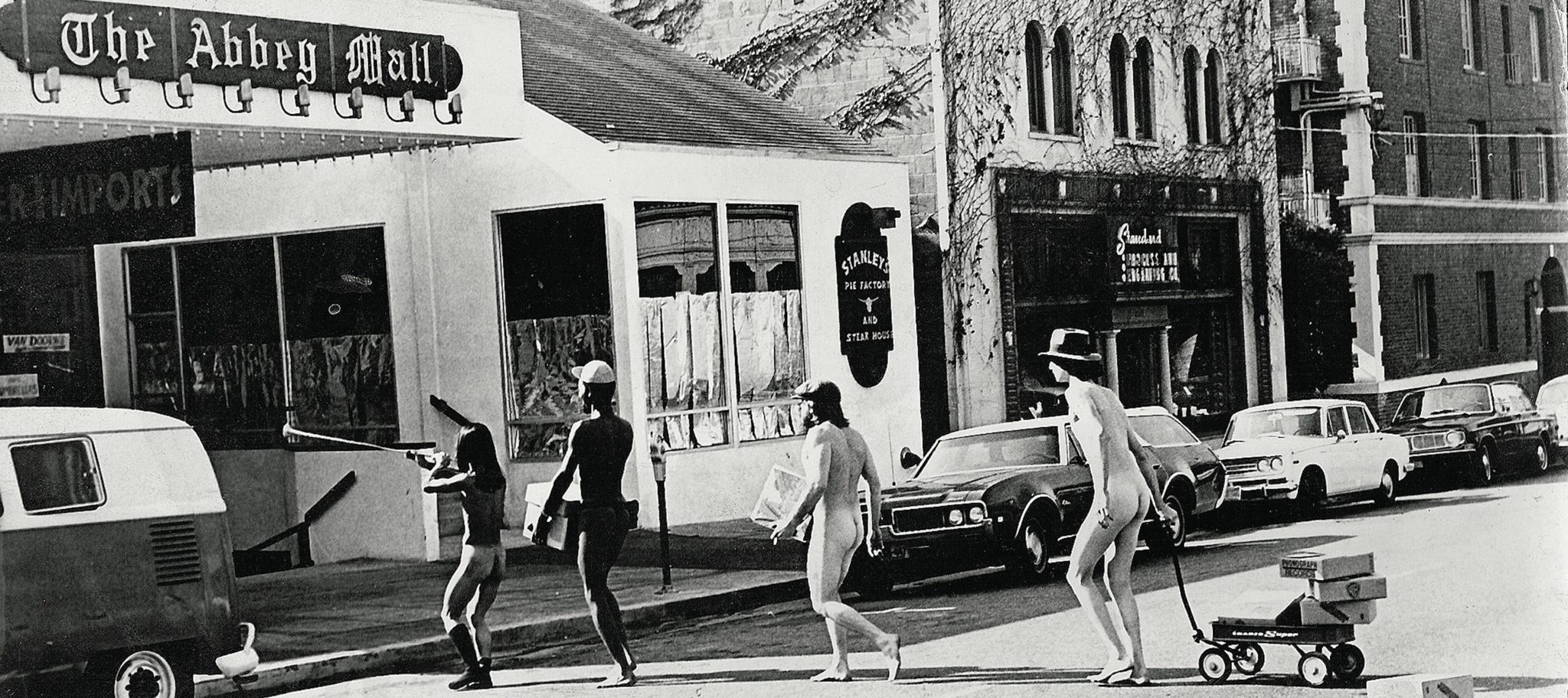

A lot has changed on Telegraph Avenue. It’s not the countercultural bazaar it once was. The bohemian hangout Caffe Med is gone, the number of head shops has dwindled, and Moe’s is the last bookstore standing.

For Telegraph’s record stores, too, the road has been rocky. The shops have faced a procession of existential threats (eBay, MP3s, Napster, Amazon, Spotify—the list goes on), and many have shuttered. Yet, somehow, Amoeba and Rasputin have weathered it all. The latter celebrated its 50th anniversary last year. The two shops share something in common: a commitment to vinyl, the medium that refuses to die.

Just check the aisles. The crate diggers are still there, fingers deftly flipping through dust jackets, sliding records from sleeves, holding them to the light for flaws. Records, it seems, are alive and well.

The birth of Telegraph as a vinyl destination can be traced to the founding in 1969 of Leopold’s Records. A group of enterprising Cal students, unhappy with the high prices at local record shops, opened what was then a collective nonprofit on Durant Avenue. A few weeks later, the People’s Park riots erupted.

“I remember having to cross police lines holding boxes of records to get to the store,” says Michael Lauer ’72, the shop’s founder. “And then when the helicopter dropped the tear gas on everybody, we shut the store down and opened up a first aid station.”

Leopold’s set the tone for Telegraph record stores to come: a vast selection of new and used vinyl, fairly priced, and staffed with enthusiastic music geeks.

“Back then, people went to record stores like they now—or used to—go to the mall … It was a destination where people socialized,” says Peter Michaels ’72, who served as chair of the collective in the early years. “And Leopold’s was the hippest place in town.”

In the early ’70s, Tower Records came to Durant. And soon after, Rasputin Music was founded by a former Leopold’s staff member. The three iconic stores established Telegraph Avenue as a music-shopping magnet. For decades, numerous smaller record shops arose and flourished in their glow.

Musically, Telegraph will forever be associated with the psychedelic rock of the ’60s, but there’s more to the soundtrack than that. When the hippies aged out, the Bay Area punk scene ignited, nurtured by shops like Universal Records, which signed local bands and held in-store concerts. When punk declined, the underground hip-hop movement exploded, with its attendant DJ culture. On Telegraph, local favorites like Hobo Junction and Mystik Journeymen peddled their cassettes on the street while Rasputin, Amoeba, and Leopold’s sold their albums on consignment.

In 2000, Lautaro opened his own record shop a block off Telegraph called Funky Riddms Records, offering hard-to-find hip-hop, funk, and reggae to vinyl-hungry DJs. Business was great—for a year. It turned out to be a grim decade for record stores.

The new millennium brought the rise of MP3s and file sharing, along with online marketplaces eBay and Amazon. Amid this new competition, Wherehouse, which had purchased and closed Leopold’s years before, went bankrupt. So did Tower. Amoeba lost millions in an ill-fated attempt to enter the MP3 market. Big music labels stopped issuing vinyl altogether. DJs began switching to CD- and MP3-based systems, which meant fewer customers for specialty shops like Funky Riddms Records. Like many record purveyors around the country, Lautaro was forced to close.

Since then, something improbable has happened. In the early 2010s, vinyl began to make a comeback, propelled in part by Gen Z’s fascination with all things analog and also, ironically, by music streaming.

“Most independent artists have been interested in putting stuff out on vinyl because … there’s no money in streaming at all,” says Marc Weinstein, cofounder of Amoeba. For these artists, selling vinyl at shows or through shops that carry independent music, like Amoeba and Rasputin, has become an important income source. Big labels, too, sensing the resurging market, started releasing LPs once again. Last year, vinyl sales reached $1 billion annually for the first time in 35 years, with a 60 percent increase in 2021 alone.

Through it all, Amoeba and Rasputin remained committed to keeping the crates stocked with potential gems, a gamble that seems to have paid off.

“We maintained the ethic of record collectors, which is what we all are,” Weinstein says. “We love the time and place that all those records came from, and that’s what we celebrate in our store…. And I think that’s what’s kept people coming.”

And so long as people keep coming, Rasputin and Amoeba will continue to sell records.

“I think [vinyl] is establishing itself as the format for hard copies for many years to come,” says Weinstein. “If you want to have the highest quality reproduction or evidence of someone’s art, it’s gotta be a vinyl record.”