After graduating from Berkeley Law in 2014, Yoana Tchoukleva, J.D. ’14, served in many roles before she found her dream job: setting up the Restorative Justice Unit of the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office.

“Justice does not necessarily have to mean incarceration,” she explains. “There are ways to hold people accountable that actually address the root causes of what happened and bring them back into the fold of the community.”

This belief traces its origins to her childhood in Sofia, Bulgaria. “Our family struggled with domestic violence and mental illness,” she said, “and ever since I was little, I wanted to understand why good people do bad things, how my father and grandmother, who loved me deeply, could also be violent and hurtful.”

It wouldn’t be until years later that she would understand how intergenerational trauma had been passed down throughout her family. “Hurt people hurt people,” she said. “And therefore, healed people can help others heal as well.”

When she was 15, Yoana moved to the United States to live with her mother. But here, too, she could see the systemic violence. “As an immigrant and someone who ran away from the violence in my own home, I started to see how horrific systemic violence has been committed here in the U.S. by European settlers, some of whom look like me. How could I live on this land in a way that does not cause and perpetuate harm?”

She attended the University of Chicago, majoring in international studies and minoring in human rights. After graduation, she went to Rwanda and studied what repair could look like in the wake of the 1994 Rwandan genocide. This is also where she was introduced to Indigenous justice practices, such as the gacaca process. Following the genocide, many individuals who caused harm were brought before circles of elders and community members, asked to listen to the stories of the people they hurt or their surviving family members, sometimes for days, and were then given the opportunity to take responsibility for their actions, make amends, and reintegrate back into the community.

“Some of my friends who were survivors of the genocide were living literally next door to people who had killed their family members. That level of courage and forgiveness, not forgetfulness, is a model for how all of us can heal from egregious systemic harm,” she says.

After Rwanda, she enrolled at Berkeley Law to learn how to help end mass incarceration. She attended the Restorative Justice Roundtable, a program at San Quentin run by men imprisoned there. “It’s really the men I met there, many of whom were serving life sentences, who taught me what it takes to break cycles of harm and violence.”

So she cofounded a student-led clinic at Berkeley Law that trained law students to represent lifers in parole board hearings. Many years later, the Post-Conviction Advocacy Project is still functioning, and dozens of people have been released on parole thanks to the work of the students.

After clerking for Judge Thelton Henderson, J.D. ’62, she served as a civil rights fellow for the Equal Justice Society in Oakland, where she worked on cases aimed at interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline and she drafted legislation making implicit bias training a requirement for all judges, lawyers, and health care professionals in the state. She continued practicing restorative justice on the side, holding reentry circles in the community.

She joined the San Francisco D.A.’s Office in 2021. “It’s the first job where the two parts of my life—my legal work and my restorative justice practice—come together. The only way we will be able to decrease the footprint of the criminal legal system and move closer to a world without jails and prisons is to offer people a positive vision of what’s possible, to show judges and decision makers that we can hold people accountable without putting them in cages, and that we can end cycles of harm rather than perpetuating them. And for that to happen, it will take all of us!”

“I’m just a mother and a teacher,” says Martha Hamilton Jones ’68. “Nothing more.”

Martha started at Cal as a part of the Class of ’53, but dropped out in the second semester of sophomore year to get married. Four kids later, she finally graduated in 1968 with a degree in Russian history.

After graduation, she began volunteering at the California Schools for the Deaf and Blind (now the site of the Clark Kerr Campus). Her first assignment was working with the most disabled child in the school, a 6-year-old named David who was profoundly deaf and totally blind since birth from rubella. He was her student for the next eight years. Despite never having seen a brailler device before, it was her job to teach David how to use it.

“I learned everything five minutes before teaching David,” Martha said. She first trained his finger to feel dots by having him match cards with dots on them and cards without. Then, she taught him words, starting with “ball” and “wall”—words only one dot different. “I labeled everything in the classroom: my name, his name, the wall, the door, the chair—everything. One day, the light went on in his head, and he realized that everything he touched had matching dots,” she recalls.

After eight years, the Schools for the Deaf and Blind moved to Fremont, and Martha remarried a prominent Berkeley doctor named John Jones, a Stanford grad who was the primary care physician for two UC presidents (Richard Atkinson and Clark Kerr) and two Cal chancellors (Albert Bowker and Robert Berdahl), and she had a fifth child, Anne.

When it was time for Anne to enter elementary school, she went to Emerson, the same place where her older siblings had gone years before. But because of Proposition 13, the school had completely changed: no music, art, after-school playground, or even a librarian.

So Martha became president of the Emerson PTA. To fill the manpower gaps left by Prop. 13, she recruited frat members on probation who needed community service work.

“I took my daughter with me to show them what a child looked like and asked them to come and run the playground after school. The city recreation director trained them on how to deal with children on the playground and gave them $400 worth of equipment,” Martha says. “And they were fantastic! They played Capture the Flag with the kids and held baseball and basketball clinics. Two of them were on the hockey team, so they took 15 children to ice skate.” The Cal athletics department even donated 200 tickets for a football game, designating it “Emerson Day” at Memorial Stadium.

Her scheme worked so well that other schools wanted to get in on the act. By the time she was done, she had 41 sororities and fraternities, totaling more than 2,000 Greeks, working at schools all over Berkeley.

There are so many other stories to tell, including how she convinced the Italian consulate to bankroll classes for Berkeley schoolchildren on Italian language, cooking, and culture, and how she got the San Francisco Opera Guild to give her $20,000 to take children to the city to attend live operas.

Three years ago, after 61 years of living in the same house in Claremont Court, she and John moved to Medford, Oregon, to be closer to Anne. They live on a lake with a huge flag in front of their house reading “Cal” on one side and “Stanford” on the other.

She has two sons who played rugby for Cal, Jeffrey Jackson ’72 and Peter Jackson ’76, and eight grandchildren, all surnamed Jackson, seven of whom—Katherine ’03, Stuart ’05, Jordan ’10, Kelsey ’12, Brett ’12, Lindsey ’12, and Conor ’18—also ended up going to Cal.

“The other one went to the Farm in Palo Alto,” she says sadly.

Jim Isenberg ’68, M.Crim. ’69, Ph.D. ’08, thinks it’s time to challenge the stereotype of the “get off my lawn” old man.

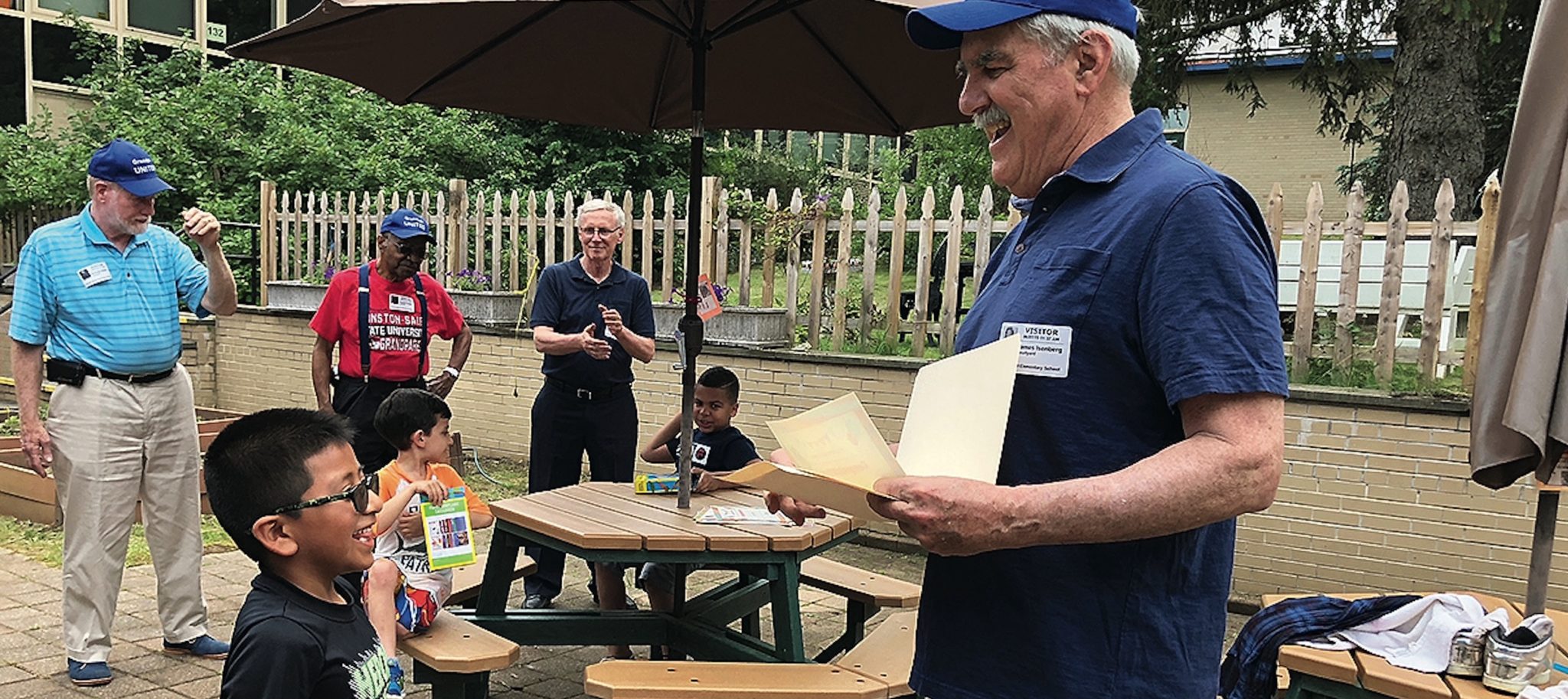

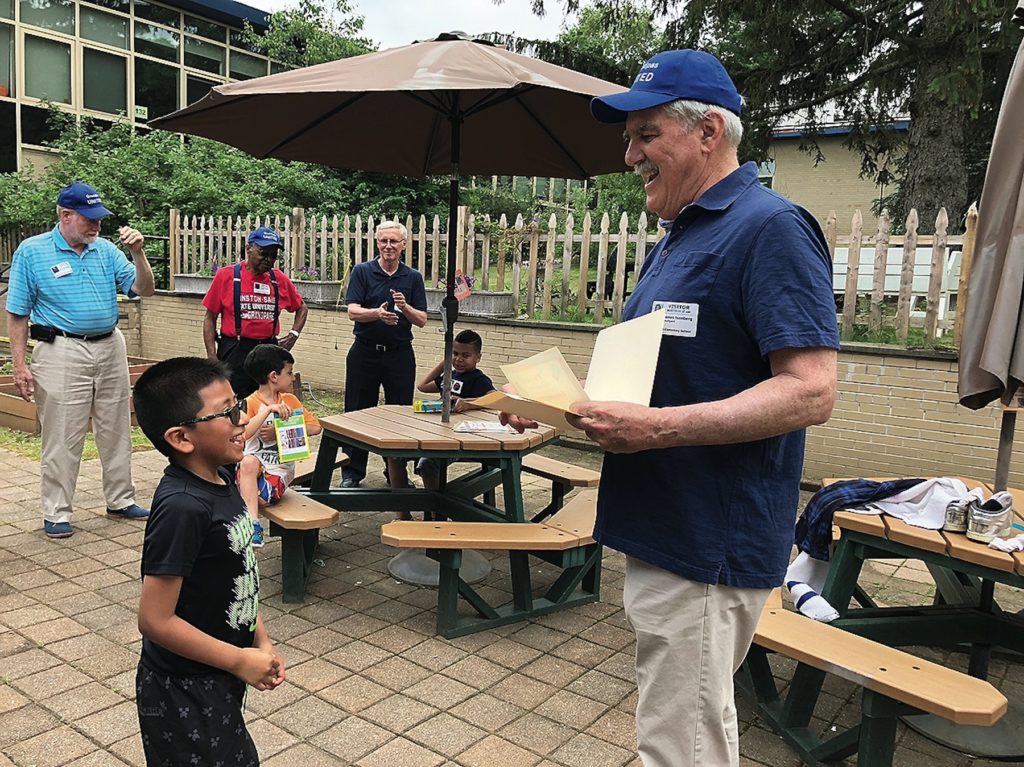

He’s cofounder of Grandpas United, a group that originated in White Plains, New York, in 2018 and has already spread to two neighboring cities. Under the slogan “Gramps, Not Grumps,” the members mentor kids and young adults without fathers and give them the same kind of unconditional love, guidance, and encouragement they give their own grandchildren.

“One of the kids I worked with wanted to be a mechanic, so I set up a three-way call with my own mechanic,” Jim says. “It’s all about doors being opened for kids who normally wouldn’t have access to those doors.”

Two years ago, Jim and his cofounder, Frank Williams, head of the White Plains Youth Bureau, added another assignment to Grandpas United’s mission: Youth Court, where minors accused of a nonviolent petty crime have their cases diverted from the criminal justice system to a real court, but with a difference—the prosecutors, defense lawyers, judge, and jury are all other kids. As part of the diversion program, they’re “sentenced” to community service or counseling, and that’s where Grandpas United comes in.

“We meet for 45 minutes to an hour every other week to talk about what he’s doing, about books, how things are with his family, anything to get him to open up a little bit,” Jim says about one boy he’s counseling. “Then we talk about things like how you deal with peer pressure when your friends want to do something screwy.”

Jim has been doing good ever since his student days, when he and Fred Cody founded the Berkeley Free Clinic. The day the clinic opened was the day of the first People’s Park march, when Alameda County sheriff’s deputies killed one person and blinded another.

He always knew he wanted to work in criminology, and after getting his bachelor’s in 1968, he moved to Boston, where he worked for the State of Massachusetts to reform the prison system after the bloody Attica prison riot in neighboring New York. Then he came back to Cal to get his master’s in 1969 from the School of Criminology. But after passing his doctoral oral exams, the school was shut down by Governor Ronald Reagan for being too critical of the criminal justice system.

Decades later, in 2006, he was attending a leadership session for the Police Corps in Utah, at which Cal professor Sandy Muir was speaking. “Maybe we can figure out a way to get you to come back,” Muir told him. So Jim retook the orals, wrote his doctoral thesis, and returned to Cal to finally get his doctorate in 2008.

Now, he wants to start a Grandpas United in Berkeley. “But this time, I’d like to have grandpas mentoring Cal students.”

If you’d like to help him set it up, email me and I’ll put you in touch with him.

Reach Martin Snapp at catman442@comcast.net.