On September 28, 2022, an opinion piece ran in the Los Angeles–based Jewish Journal that carried the alarming headline, “Berkeley Develops Jewish-Free Zones.”

It was written by Ken Marcus, an alumnus of Berkeley Law (J.D. ’91) and a former assistant secretary for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Education in the Trump administration. He was reacting to news from the month before that Berkeley Law Students for Justice in Palestine (LSJP) had adopted a bylaw stating that they would not invite speakers who support Zionism or Israel’s policies. The bylaw also stipulated support for BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions), and required members to participate in a “Palestine 101” training about the plight of Palestinians. It was also adopted by nine other student groups including Middle Eastern and North African Law Students Association, Law Students of African Descent, Asian Pacific American Law Students Association, Women of Berkeley Law, and the Queer Caucus.

Marcus was scandalized, declaring the bylaw both unlawful and morally repugnant. He ended his piece: “The students should be ashamed of themselves. As should grownups who stand quietly by or mutter meekly about free speech as university spaces go as the Nazis’ infamous call, judenfrei. Jewish-free.”

Not surprisingly, the story caught fire on social media, especially after Barbra Streisand tweeted to her nearly 800,000 followers, “When does anti-Zionism bleed into broad anti-Semitism?” Stories began to appear in traditional media outlets as well, as Berkeley Law Dean Erwin Chemerinsky responded at length in various forms, including letters sent directly to the Jewish Journal and an opinion piece of his own in the Daily Beast. He wrote that “the widespread media attention to recent events at Berkeley Law are stunningly misleading and inaccurate … Freedom of speech, dissent, and debate is alive and well at Berkeley.”

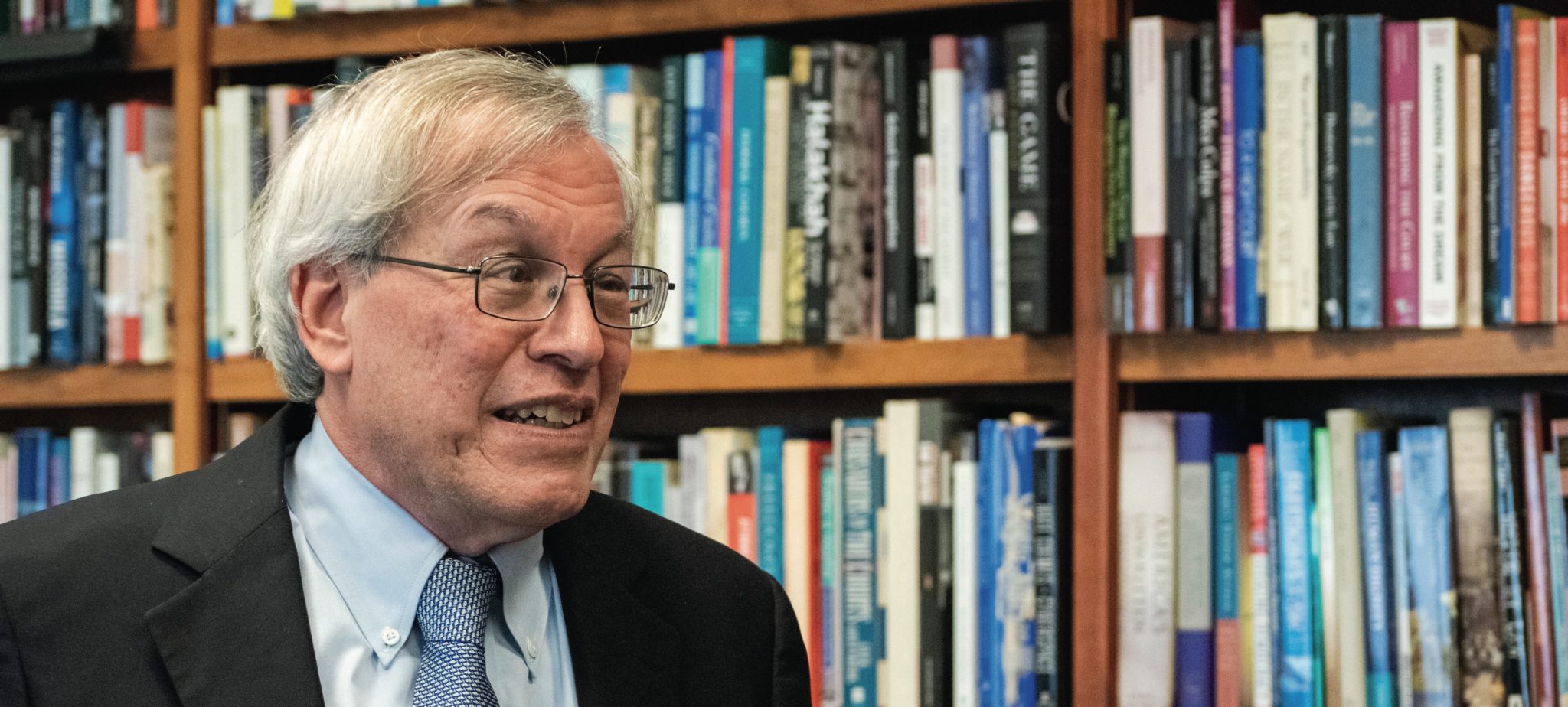

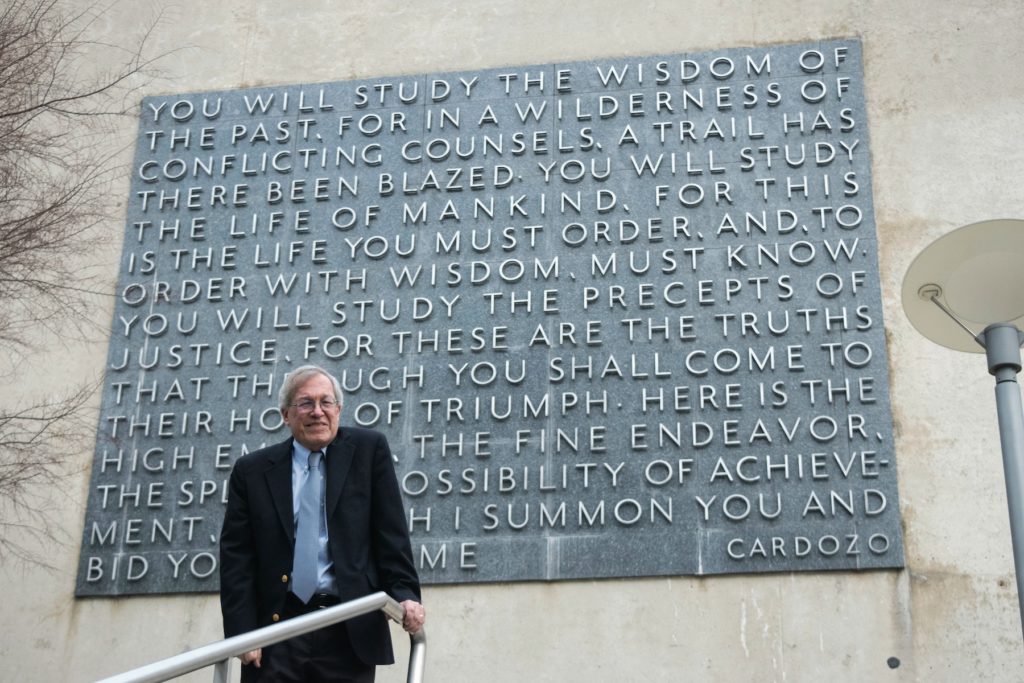

Curious to know more, I reached out to Chemerinsky, who readily agreed to sit for an interview in his office.

Professor Chemerinsky became dean of Berkeley Law in 2017 after several years as founding dean of UC Irvine School of Law. One of the most cited legal scholars in America, he has authored more than 200 law review articles as well as 16 books, including, most recently, Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism (2022). He has also argued numerous cases, including before the U.S. Supreme Court.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with the most basic question. Are there any Jewish-free zones at Berkeley?

Of course not. There are no Jewish-free zones at Berkeley Law, there are no Jewish-free zones on the campus. Indeed, we have very strict regulations on the campus and at the law school that prohibit religious discrimination. We also have at the law school an all-comers policy, meaning that every student group and every student-organized event must be open to all students.

Given that policy, it sounds like it would be an easy thing for a Jewish student to challenge the groups in question by petitioning to become a member.

If ever a student group were to exclude someone for being Jewish, that would violate the campus rules, the law school rules, and be a basis for discipline. That’s not what this is about, though. And that’s why the headline of Ken Marcus’s article is so deceptive and distorted.

Student groups can always choose speakers on the basis of the viewpoint of the speakers. The Jewish law students don’t have to invite Holocaust deniers. The law student Republican group doesn’t have to invite socialists, the Black law students don’t have to invite white supremacists. On the other hand, there can’t be discrimination based on race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation.

Part of what I hear you saying is that you can be anti-Israel and anti-Zionist without necessarily being anti-Jew or antisemitic.

I think many Jews would perceive excluding those who support Zionism as a form of antisemitism. And I completely understand that because it’s inconsistent with a key part of many Jews’ identity, including mine. Indeed, 24 law professors here at Berkeley signed a letter condemning the LSJP bylaw as a form of antisemitism.

It is important to separate being against the existence of Israel from being against Israel’s policies. I am against many of Israel’s human rights policies, but I strongly support the existence of Israel. I don’t think anyone would say that I, as a Jew, am anti-Jewish. On the other hand, I think you find people who oppose Israel often speaking of it in anti-Jewish terms.

One thing that jumped out at me from the faculty statement was that the bylaws were “discriminatory.” Discriminatory sounds punishable.

It’s not. I have gotten so many emails echoing what seems to be Ken Marcus’s position, that we should prohibit the bylaws and punish the students. But no, the law school cannot, consistent with the First Amendment, prohibit such bylaws, or punish such students. They have the right to choose speakers for their events based on viewpoint. It would be punishable if they discriminated based on religion (or race or sex or sexual orientation) in inviting speakers.

There’s nothing you can do?

We can do something. I sent a letter to the leaders of all student groups, expressing my strong disagreement with their bylaws, and how they were inconsistent with our values. Those student groups were very angry at me for what I said, but they have the right to speak, and so do I. As I mentioned, two dozen faculty also signed a statement condemning the bylaw.

You sound a little dismayed that this has become such a big issue.

Oh, I’m tremendously dismayed. Let me tell you the chronology. I learned of this proposed bylaw on the first day of school, Monday, August 22. I talked to a number of Jewish students and the Jewish Law Students Association officers, put out my letter, and no additional student groups adopted the bylaw. It got a flurry of media attention, especially in the Jewish and Israeli press, and Fox News at the end of that week. By the beginning of the following week, the issue had faded in the media, and faded within the law school. I would say 90 percent of the students and faculty never heard anything about it. And then the Marcus article came out at the end of September, and it exploded into a national issue. Nobody had been excluded from speaking. And the headline of “Jewish-Free Zones” attracted so much attention, and so much media, and so much anger, and so much email, all based on a very distorted description of what was going on.

Do you think it would have been a story at all without social media?

I think that going viral gave it enormous force. I think the headline being so much worse than even the story helped it get picked up. There has also been some coverage that I think is quite good, but I’ve seen that truth doesn’t necessarily win out over falsehood in the media.

To the extent that some people start with a narrative about college campuses, or Berkeley, being antisemitic, this fits their preconception. I’m stunned by how many people wrote me messages wanting to talk about the antisemitism within Berkeley Law. But I want to say: Have you ever even been here? Have you ever been in the building? They have the story they want to tell about how students and faculty are treated, not having ever been here.

I think it’s also clear that some of this is coming from the right wing. Did you see the truck last week? There was a truck that went around campus, and on the truck, it said, “If you want a Jewish-free zone at Berkeley, raise your right hand,” with a picture of Hitler doing the “Heil Hitler” salute. A far-right group paid for it. Then the group paid for a truck with a panel listing the names of students who were part of groups that signed the bylaw under the heading, “Berkeley Law’s Antisemitic Class of 2023.” It was despicable for them to put names on the truck, including of students in their group who voted against the bylaw.

Changing topics slightly, if you asked me which side of the political spectrum most opposed free speech, I would usually have said the right. Increasingly, though, I see it from the left. But it depends on the content of the speech, doesn’t it?

Sure it does. And here, I would emphasize that I’m defending the right of LSJP to invite the speakers that they choose, in terms of viewpoints. And I’m also exercising my own free speech rights in criticizing what they say. And the irony of this is, those on one side believe that unless these bylaws are prohibited and punished, the school is not doing enough. The other side would say my criticizing the LSJP statement is making them feel unwelcome.

Which brings me to another idea that is popular amongst the current generation: the idea of safe spaces and wanting to prioritize the feeling of safety in the academic setting.

The LSJP statement was phrased explicitly in those terms. And it’s easy for the Jewish students, in turn, to say the LSJP bylaws make them feel unsafe. I think the difficulty is that it often equates I am offended with I feel unsafe. And while I think the campus has the obligation to protect the physical safety of every student, staff, and faculty member, I don’t think we have to, or should, set out to protect students from being offended by what they don’t want to hear.

I pulled a quote from your 2017 book Free Speech on Campus that you wrote with Howard Gillman. It begins, “Words can cause real harm and interfere with a person’s education. Campuses have the duty to act—sometimes legally, always morally—to protect their students from injury.”

But if you put that back into the context of the chapter, it’s very clear that we don’t think the government—public universities—can prohibit hate speech on the grounds that it’s offensive.

Right. You also write, “Campuses can never punish or censor expression of ideas, however offensive, because otherwise they cannot perform their function of promoting inquiry, discovery, and the dissemination of new knowledge.” I guess what I’m asking is, how do we square those two ideas, in practice?

We protect the rights of students to say everything that’s protected by the First Amendment. And we recognize that there are some limits to freedom of speech. It’s not an absolute right.

To push a little, what about hate speech, which we now have scientific evidence can cause real harm?

I can respond on two levels.

First, descriptively: The law is clear that hate speech is protected by the First Amendment. Every campus hate speech code to be challenged in court was declared unconstitutional. So let’s be clear that under the current law, we can’t outlaw hate speech.

We can then have a normative discussion: Should hate speech be protected by the First Amendment or not? When I teach First Amendment law, we have that discussion, but it’s a different discussion than about what the current law provides.

You’re teaching in a law school with some of the best students in the country. Do you find that your views of free speech and theirs differ?

Yes, although I don’t want to overstate it. One advantage of having taught this subject for 43 years is I’ve seen the evolution of student attitudes toward it. My generation witnessed the Civil Rights Movement, and many of us, including me, participated in the anti–Vietnam War protests. That’s our image of free speech. For this generation, that’s as long ago as World War I was for me. For many of them, free speech is the vitriol of the internet. And this is the first generation we taught from a young age that bullying is wrong. I admire that they’ve internalized that message.

So, my guess is, if we were to do a free speech survey, there’d be more of a commitment to the principle of free speech among the faculty than among students. And, again, I don’t mean to overstate. I think most students still would be very strongly committed to free speech. But I think there are many who are skeptical of it. And certainly some of my colleagues are as well.

So, is the ghost of Mario Savio wandering Sproul Plaza, wringing his hands?

No! You know, I’m on a task force that, just today, was drafting a set of Berkeley principles of free speech, and the first sentence invokes him with the Free Speech Movement.

But it’s a different time and the issues are different now.