Every year, October brings two things: Halloween and Nobel Week. This year, the Berkeley laureates (yes, multiple!) seemed to combine the two.

“Cells are like M&M’S; they have a sugar coating,” Carolyn Bertozzi, Ph.D. ’93, said, by way of explaining her work. On October 5, she became the eighth woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing a method she dubbed bioorthogonal chemistry while still a professor at Berkeley, where she taught for nearly two decades. Now on the faculty at Stanford, she originally discovered and applied bioorthogonal reactions to study glycobiology—those sugars that coat the outside of cells.

Bioorthogonal chemistry takes “click chemistry” (developed by her Nobel corecipients, K. Barry Sharpless and Morten Meldal) and applies it to living organisms. It refers to chemical reactions “not interacting with or interfering with biology,” Bertozzi explained in a video press conference after the award announcement; in other words, reactions that take place without disrupting the normal chemistry of the cell.

Laureate John Clauser continues the Halloween theme with his Nobel Prize in Physics for an experiment he conducted on quantum entanglement while a postdoc at Berkeley in the early ’70s. In quantum entanglement, what happens to one particle in an entangled pair determines what happens to the other one, even if the two are spaced far apart. Albert Einstein famously called the weird phenomenon “spooky action at a distance.”

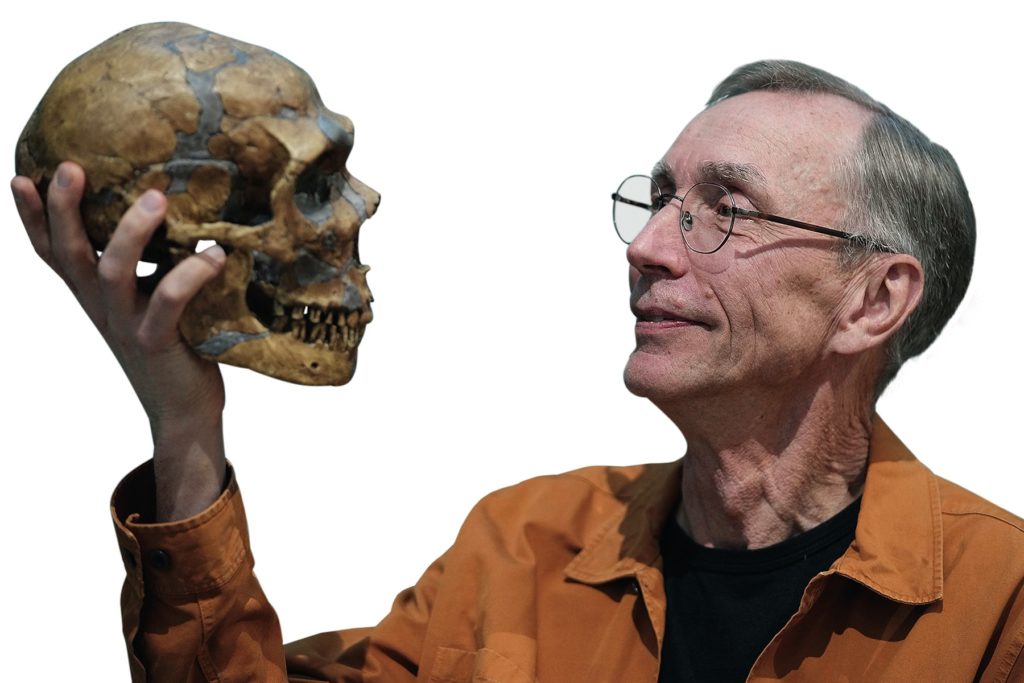

Finally, former Berkeley postdoctoral fellow Svante Pääbo won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for successfully sequencing the Neanderthal genome in 2010. His research created a new scientific discipline, called paleogenomics, and helped show how ancient genes transferred to present-day humans. The way these genes flowed is still physiologically relevant; for example, it affects how our current immune system reacts to infections.

“By revealing genetic differences that distinguish all living humans from extinct hominins, his discoveries provide the basis for exploring what makes us uniquely human,” the Nobel Assembly press release reads.

Pääbo accomplished this by isolating and analyzing DNA from the bones of three female Neanderthals who lived 40,000 years ago. We hope their ghosts didn’t come back to haunt this past Halloween.