Anthony Lee simply wanted to go to high school.

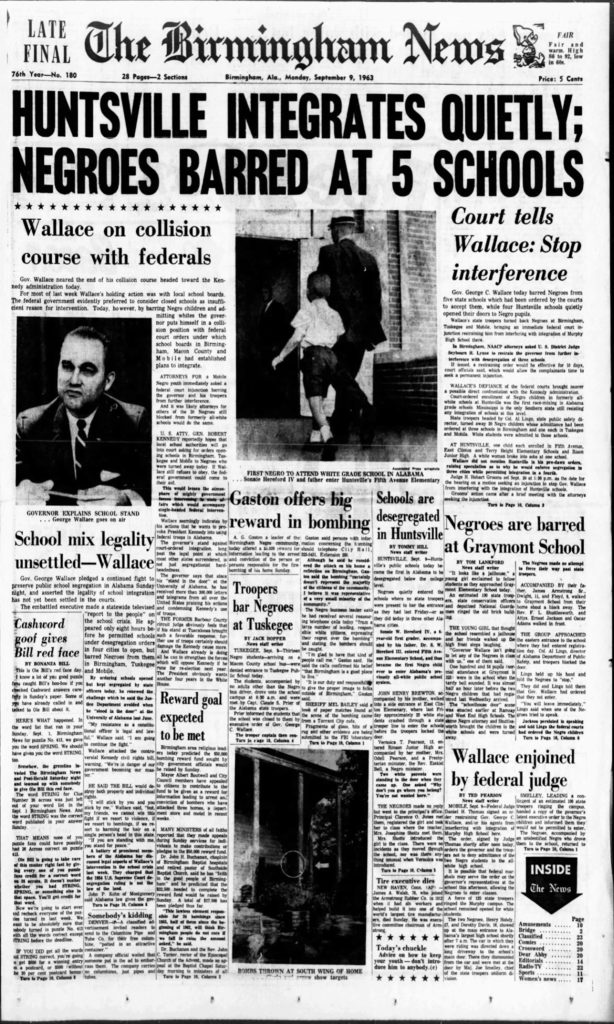

Because he was Black and because this was Alabama, going to all-white Tuskegee High School had not been allowed for Lee. The local school board, however, had cracked open the door in 1963, agreeing to limited desegregation. But on the first day of classes, Lee was one of 13 Black pupils blocked from entering the school by a phalanx of state troopers under orders from Governor George Wallace.

Unlike many confrontations across the South during the struggle to end Jim Crow, there was no violence that day, but the incident marked a critical moment in the legal siege to allow Black pupils to attend all-white public schools in Alabama—nearly a decade after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation in classrooms must end “with all deliberate speed.” It is also the story of how four Berkeley-trained lawyers for the U.S. Department of Justice helped overturn the racial caste system that consigned Black students to inferior schools.

That Tuskegee was the locus of the battle was not unusual. The small city, seat of Macon County, about 40 miles east of Montgomery, was home to Tuskegee Institute, the historically Black school founded in 1881, and a Veterans Administration hospital established in 1923. During World War II, the school became the training base for the Black military pilots and air crews who became famously known as the Tuskegee Airmen. The entirely Black staffs of the school and the hospital were better off financially and organizationally than most rural Southerners at the time. Of all Alabama counties, Macon had the highest percentage of Black high school and college graduates. White schools were off-limits to them, however.

Like residents of many college towns, Tuskegee’s citizens were imbued with a sense of civic responsibility and social justice. The Tuskegee Civic Association (TCA), established in 1941, won major court battles to protect voter rights in 1960 and 1961. Under the leadership of Charles Gomillion, a professor of sociology at the college, the TCA’s mission was clear: “The study and interpretation of local and national trends and problems; the collection and dissemination of useful civic and political data; and intelligent and courageous civic action.”

After the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 helped protect voting rights, the battle shifted to school desegregation. The TCA, of which Anthony Lee’s father was a member, was ready. Joined by other students, Lee became a lead plaintiff in a case filed in federal court in Montgomery in January 1963, seven months before Wallace’s troopers blocked the students at the high school. The case, called Anthony T. Lee et al. v. Macon County Board of Education, is the subject of a new book, Revolution by Law, by Brian K. Landsberg, one of the Berkeley-trained lawyers involved in the case.

Landsberg, who graduated from Berke-ley in 1959 and from the law school (then widely referred to as Boalt) in 1962, was recruited by John Doar, J.D. ’49, another Berkeley law graduate and legendary chief of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division from 1960 to 1967. A white Republican from Wisconsin who became known as “the face of the Justice Department in the segregated South,” Doar seemed fearless amidst the violence of the South.

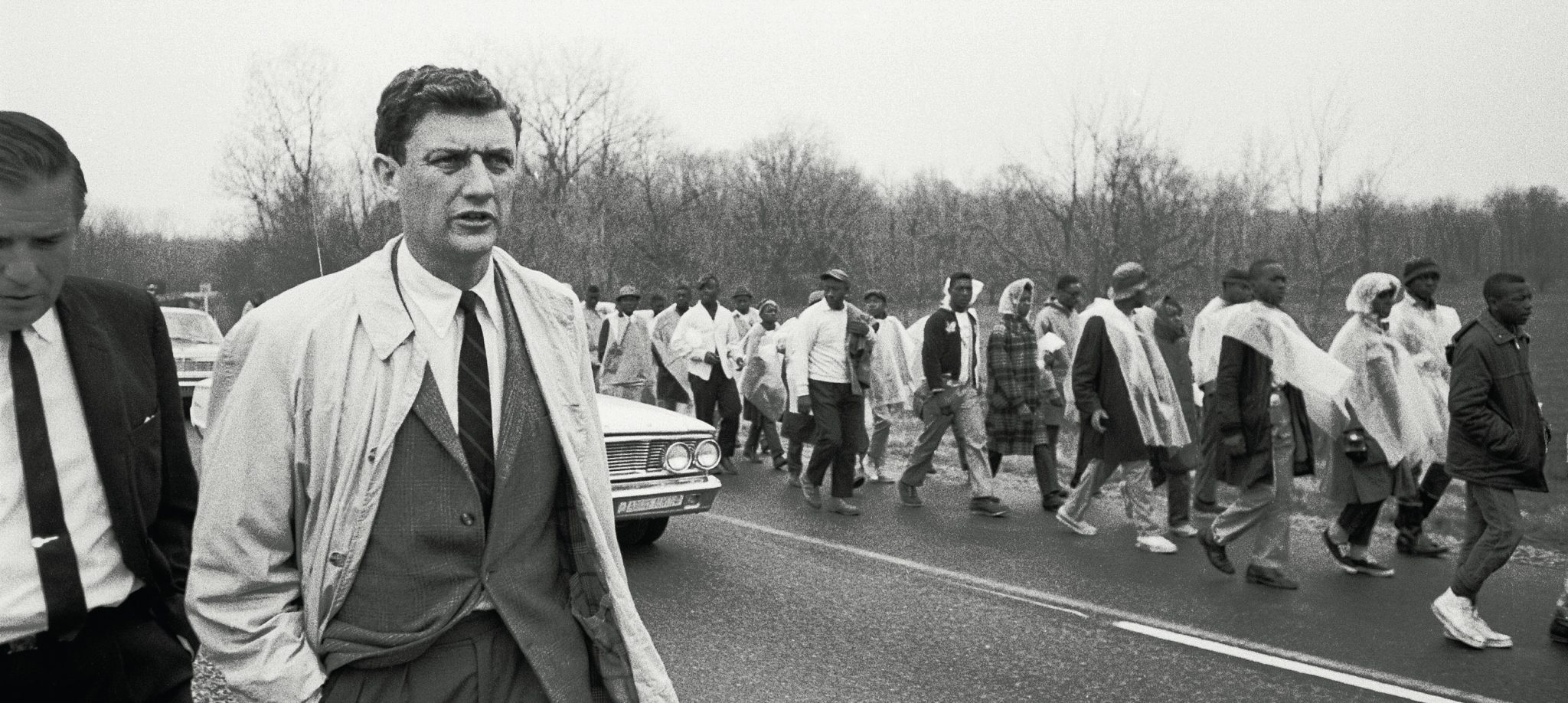

Thelton Henderson ’55, J.D. ’62, another Boalt graduate who became a federal judge, recalled how Doar, in 1963, after the funeral of assassinated civil rights leader Medgar Evers, in Jackson, Mississippi, prevented a likely battle between police and demonstrators.

“I was fully expecting the riot to result in multiple deaths, and I did not want to be among the casualties,” Henderson told an interviewer.

“I turned to see a tall white man stepping from behind the police line to stand between the police and the marchers. He looked like John Wayne—maybe a little thinner, but the same imposing scale. I’ll never forget the moment I heard him say, ‘My name is John Doar. D-o-a-r.’ He always spelled his name, and with good reason, as a lot of people were going to write about what happened that day.

“I don’t remember the specific words he used, or what he said to calm the angry crowd, but John Doar stood that day, in the line of fire, and prevented what would otherwise have been a slaughter. He had the courage to stand where no one else would dare to tread, and only God will know how many lives were saved.”

Landsberg, now an emeritus professor at McGeorge School of Law in Sacramento, arrived in Alabama in 1964, the year after Governor Wallace gave his inaugural speech from the capitol steps, praising his state as the “very heart of the great Anglo-Saxon Southland” and vowing to uphold “segregation forever.”

On Landsberg’s first trip to Tuscaloosa, he called Washington from the phone in his hotel room. The bellhop, who was Black, warned him, “You’d probably want to know that they’re listening in on your calls at the desk.” Landsberg, who had grown up in Sacramento, recalled, “It made me very aware and careful.”

In 1965, he was standing on the Selma side of the Edmund Pettus Bridge on what became known as Bloody Sunday, when peaceful marchers for voting rights were attacked by the notoriously vicious Sheriff Jim Clark and his mounted posse. The panicked marchers, beaten and tear-gassed, streamed past Landsberg to escape the bedlam. To his frustration, Landsberg could only observe. “We were law enforcement people. We weren’t there to demonstrate or to be part of a demonstration so I couldn’t march across the bridge with the marchers, or I would be identified as taking sides, basically,” he said. “Our job was strictly neutral.”

Since its inception, Tuskegee University (previously called Tuskegee Institute) has enjoyed a national reputation. Its founder, Booker T. Washington, envisioned it as a school where former slaves and their children could learn basic skills, like brickmaking and dressmaking, and thus earn money and respect in the segregated South without threatening the white power structure. “The Negro has the right to study law,” Washington wrote in 1899, “but success will come to the race sooner if it produces intelligent, thrifty farmers, mechanics, and housekeepers to support the lawyers.”

In 1960, Macon County was one of 177 counties in the United States to have maintained a majority Black population for 50 years. Most were in the Deep South, a stretch called the Black Belt, originally for the richness of the soil, but later for the predominance of Black residents.

Between 1950 and 1960, the population of the city of Tuskegee, which was also majority Black, decreased by about 5,000 residents to 1,750. The drop was not caused by migration, but by an extraordinary effort to deprive Black citizens of their political power through gerrymandering: The state legislature in 1957 passed into law a bill to redraw the city’s boundaries to place most of its Black residents—including those at the college—outside the city limits. Less than a dozen Black voters were left in the redrawn city. In response, Black citizens began a boycott of the white-owned businesses along what was known as Confederate Square.

Stanley Smith, a professor of sociology at Tuskegee and an officer of the TCA, told New Yorker reporter (and, later, Berkeley journalism professor) Bernard Taper ’45, “It was the gerrymander that brought us together. Before that, we professional people had the feeling that it was possible for us to go downtown and obtain special privileges. When this happened—the gerrymander—we discovered that the whites who ran things didn’t regard us as different in any significant way from the most backward members of our race, and that historically this had always been so, and we had just never faced it.”

Gomillion sued, and the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in November 1960 ruled unanimously in Gomillion v. Lightfoot that the new lines violated the Fifteenth Amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The original boundaries were restored.

While Gomillion’s case was being decided, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, created by the 1957 law, began examining how Southern states blocked most Black people from registering to vote. The frustrated citizens of Macon County presented “a stream of petitions and meticulously documented complaints,” as one account put it, about the obstacles they faced. William P. Mitchell, executive secretary of the TCA, was one of those who testified before the commission. He had managed to become a registered voter—after three visits to the county Board of Registrars, two appearances in federal district court, two appeals to the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and a petition to the U.S. Supreme Court.

While the Civil Rights Commission was powerless to do much about the situation, the Civil Rights Division wasn’t. Doar’s office filed suit in federal district court in Montgomery against the members of the Board of Registrars of Macon County.

To build the government case, Doar relied on the files of the TCA to detail tactics such as requiring Blacks—and Blacks only—to write out long portions of the U.S. Constitution without error before they could register. While Blacks were forced to wait, whites went to the head of registration lines and routinely got help with their forms, while Blacks were given none. And, often, Black registrants were not notified whether their applications had been accepted or rejected.

Ruling in 1961 against the Macon County election officials, Judge Frank Johnson, known for several courageous decisions involving desegregation, ordered 64 Black applicants who had been rejected to be registered at once. He ordered the Board of Registrars to maintain regular hours and accept applicants as they showed up. No one could be required to copy more than 50 words and the board could not disqualify any Black applicant whose performance was equal to the least-qualified white applicant ever accepted. This last element, known as “freezing,” was developed by Doar’s associate, David Norman, J.D. ’56, another of the Berkeley-trained lawyers in the Civil Rights Division.

Blind since youth, Norman had been working in an aircraft plant in Southern California when the state, recognizing his academic potential, paid his way through Berkeley. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa, then third in his law school class before joining the Justice Department in 1956.

The Johnson ruling, and “freezing,” was subsequently challenged all the way to the Supreme Court, which upheld it in 1966.

For the fight to desegregate Tuskegee schools, the TCA selected Fred Gray, a Black lawyer who had represented Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr., to represent the families. After Gray filed the case (also in Frank Johnson’s court), the Macon County school board agreed to begin—very slowly—to allow Black pupils to attend the public high school in Tuskegee. Thirteen students were selected to attend by the school district, including Anthony Lee and Willie Wyatt, who were entering their senior year.

When the case was filed, Judge Johnson took the unusual step of naming the United States, as represented by Doar and the Civil Rights Division, as both a party and a friend of the court, amicus curiae. In effect, he joined two branches of the federal government—the executive branch (Justice Department) and the judicial branch (Judge Johnson’s court)—together, and, in doing so, strengthened the law enforcement and research powers of the department to deal with Governor Wallace and the apparatus of segregation.

Before Tuskegee schools started that year, Doar met with the students, telling them, “You are entering something you have the right to do. The judge ruled that you have the right to do this, but there are some things that might happen, but I want you to understand we are here to protect you,” recalled Wyatt later.

“It gave you a good feeling having the Department of Justice and FBI and all those other people there,” Wyatt told an interviewer.

On September 9, the day the troopers again blocked the students from entering the school, events moved quickly. The government filed a new suit, signed by Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to enjoin Wallace from interfering in what the state had deemed a local question. At 5:15 p.m., Johnson issued an order blocking Wallace and state troopers from further action. At 7:09 p.m., Wallace called up the Alabama National Guard to replace the police. The next morning, President John Kennedy asserted federal authority over the National Guard, wresting control from the governor.

The 13 Black students soon were the only pupils at Tuskegee High School. The white students deserted en masse, transferring to other high schools in the county or enrolling in Macon Academy, one of the many private institutions then established to maintain segregated schools.

In January 1964, the Alabama State Board of Education ordered Tuskegee High School closed, and the Black students sent back to Tuskegee Institute High, their original all-Black school. Gray went to federal court again, this time challenging the constitutionality of the order and the state law that gave financial support to segregated institutions like Macon Academy. Johnson blocked the state order and instead sent the students to the two other high schools in the county, six to each. Lee and Wyatt ended up at Macon County High School in Notasulga. In a day marred by violence outside the school, the mayor of Notasulga blocked the students from entering, saying their presence would create a fire hazard. In the melee, a photographer was beaten with a cattle prod by Sheriff Clark, who often wore a button with his one-word position on desegregation: “NEVER.”

Under the nearly constant watch of fed- eral law enforcement, life at the two schools eventually settled down, and Lee and Wyatt both graduated. Each went to Auburn Uni—–‑ versity. Lee graduated, the first Black student at Auburn to go through the four-year program. Wyatt transferred after his first year and graduated instead from Tuskegee.

For attorney Gray, the case was still very much alive. He now realized that if Wallace had the power to close schools, he also had the power to desegregate them. He later recalled that the realization hit him “like the burning bush speaking to Moses.” In his court filings, he now added the governor and state officials as defendants in the case and asked for statewide relief. Soon a trial was scheduled.

The Civil Rights Division assigned St. John Barrett, J.D. ’48, yet another Boalt graduate and one of its top litigators, to the case. A former deputy district attorney in Alameda County, Barrett, known to friends as “Slim,” joined the Justice Department in 1955 and became involved in many of the high-profile cases of the era, including James Meredith’s enrollment at the University of Mississippi in 1962. Doar once said, “I had such confidence in him. I felt he had a much better grasp of civil rights law than I did.” Landsberg was placed in charge of organizing evidence for the trial.

The case reached a climax in March 1967, when a three-member federal court ordered statewide desegregation in Alabama. State officials, the ruling said, “through their control and influence over the local school boards, flouted every effort to make the Fourteenth Amendment a meaningful reality to Negro school children in Alabama.”

The Alabama Journal editorialized that the decision “became inevitable when former Gov. George Wallace sent armed troopers to Tuskegee on that sad morning in September of 1963 to prevent children and teachers from entering school, even though the community—albeit reluctantly—was prepared to carry out the orders of the court as gracefully as it could in desegregating its schools.”

George Wallace was no longer governor by this time. He had been succeeded by his wife, Lurleen, who, in the Wallace tradition, denounced the ruling as “rendered in malice and animosity” and a “physical impossibility” to implement.

But implement it, Alabama did. “The result was that, while some one-race schools remained, the schools of Alabama became among the most racially integrated in the country,” Landsberg writes in his book. “By 1970, 36.5 percent of African American students in Alabama public schools attended majority white schools, up from 8.6 percent two years earlier.”

In a way, Doar had seen the possibility of this outcome even before Wallace blocked the Tuskegee students on that September morning. In June 1963, he spoke to the TCA, which recorded his remarks.

“If this country had listened a little more carefully to the grievances of the Tuskegee Civic Association, if we had listened a little, paid a little attention—I’m not talking about just the people in the South. I’m not talking about the people in Alabama, because it isn’t just their problem. It’s the problem of the people in Wisconsin, where I live, in California and New York. And it isn’t a question of being self-righteous about the problems that exist in the South and not looking at the problems that exist among our own people up in the North. If we had looked at the problems a little more closely and thought about them more carefully and then resolved to do something about them, perhaps we might not be faced with the difficult situation that we now face in this country in the summer of 1963.”

Rob Gunnison is a lecturer at Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, where he previously served as the director of school affairs.