Robots can do a great many things, but they can’t make art. That view, common even among AI boosters, has taken a hit with the recent torrent of innovation in artificial intelligence.

In late 2022 ChatGPT was unleashed on the world and was met with collective astonishment. So-called natural language AI tools have been around for decades in the form of chatbots, AI assistants, and various types of text generators. Familiar ones like Apple’s Siri and IBM’s Watson were impressive and even useful—but perhaps more artificial than truly intelligent. ChatGPT was different. Its prose was, at times, so good, so natural, that it felt eerily human.

And the magic that ChatGPT wielded with language, other new generative AI tools such as DALL-E 2 and Midjourney cast with images and video. The output of these tools has won photography and fine art competitions and even passed medical boards and the bar exam. They are smart. They are creative. And they learn. Like us.

Like many technological leaps of magnitude, these new tools prompted strong reactions. In the media, early exuberance was soon drowned out by fear. Writers wondered, “Can this robot do what I do, only faster?” Teachers questioned whether their students did their assignments at all. Journalists fretted over the threat of deep-faked photos, videos, and audio. And AI researchers—of all people!—warned that this could eventually lead to the end of humanity itself.

Whether these tools represent the beginning of something or the end of everything, there’s no question that they herald a future in which AI plays an ever-increasing role in a domain long considered exclusively human: the arts.

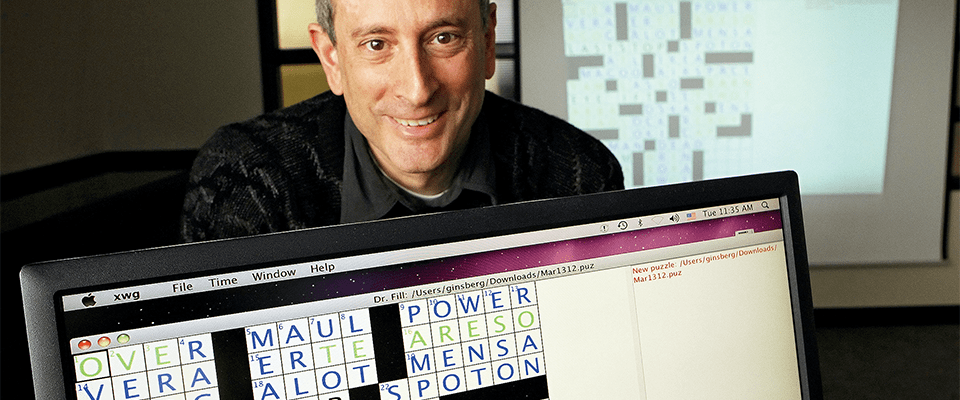

So who better to take the temperature of this moment than Berkeley robotics professor Ken Goldberg. As an artist and researcher, he has long straddled the worlds of art and technology. His deep fascination with remotely operated robots has yielded both innovations in telesurgery and numerous art installations such as Telegarden, which allowed users to plant and care for seedlings from afar using a robotic arm.

Goldberg argues for the embrace of new generative technologies, and he walks it like he talks it. His upcoming exhibition for the Getty Museum in Los Angeles will incorporate generative AI.

The discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

As both an AI expert and an artist, what was your experience of the arrival of ChatGPT?

It is a major milestone. No doubt about it. I had been following GPT-3 and had some experience also with Google’s PaLM 2. And I was very skeptical. But then I got to try ChatGPT myself. And I was surprised! It was very, very good at answering complex questions. This is something I did not expect to see in the next decade, or really in my lifetime.

At the same time, I feel it’s important not to jump to the conclusion that we now have artificial general intelligence. I’m particularly interested in the element of creativity in ChatGPT’s responses. It doesn’t give “just the facts, ma’am” kind of answers. I didn’t expect that.

This is something I did not expect to see in the next decade, or really in my lifetime.

I wanted to see how creative it could be. I gave it an abstract from one of my papers and asked, How would you take this in a novel research direction? Give me ten ways it could be extended. I was surprised that two of those ideas were interesting. I mean, if my grad student had come to me and suggested those, I would say, hmm, there’s definitely something to think about here.

Then I gave it two abstracts and asked it to combine them in novel and interesting ways. That’s what we do in the lab, and I emphasize this a lot with students: How can you take A+B and get C? Some of our best ideas come from two different corners of the lab. So I tried that with ChatGPT and the responses were again very interesting.

You’ve been quoted in the past saying that robots would never be creative. With all of this recent innovation, have your views shifted on that?

Yes. I fully admit that I was wrong about that. To evaluate ChatGPT’s creativity, I used the Torrance creativity test. It’s been around since the ’60s. You ask a student to come up with as many uses for a paperclip as they can think of in three minutes. It’s a classic brainstorming exercise. To do well, the student must think outside the box.

So I tried this on ChatGPT. “List ten creative uses for a pencil.” It listed ten in seconds. They were all reasonable, and quite different. So I said, OK, give me a hundred. And boom. It shot back a hundred uses. I was blown away.

It’s not quite the same thing that humans do, but it’s undeniably creative.

But then I wondered if anybody ever wrote about that on the internet, a hundred creative uses for a pencil. So I looked it up with Google and sure enough it was in some document somewhere…

Maybe if I could try uses for a guitar pick. I searched the internet and didn’t find anything. So I gave that to ChatGPT and it spit out a hundred uses. They were all interesting and different. One of them was a miniature sail for a toy boat. That one made my jaw drop.

And when you think about how these large language models are supposed to work, predicting the next word—it feels like it requires some understanding of physics for it to suggest a miniature sail.

Yes; it feels that way. But what’s really interesting is that there may be some structure in language that allows this sort of synthesis to occur. Language evolved to be a very efficient way to encode our experiences and ideas. There are some who say it’s just memorizing the internet. That isn’t accurate. ChatGPT has compressed a vast number of texts into a set of relationships between words that somehow allows it to be creative, or what we might call artificial creativity. It’s not quite the same thing that humans do, but it’s undeniably creative.

By the way, all researchers and artists use material from prior work. As Picasso purportedly said, “Good artists borrow; great artists steal.”

Can you explain the difference between creativity and artificial creativity?

The artificial creativity of ChatGPT and similar systems emerges from many examples of words and images. But I believe human creativity also comes from lived experience and emotions. So I think humans still have an advantage.

There’s a professor at Wharton, Ethan Mollick. He reported an experiment by his colleagues who were teaching a product design class. The students had to come up with an elevator pitch for a new product. They also asked ChatGPT-4 to come up with ideas. Then they put all the ideas together and asked a panel to evaluate them. Surprisingly, 35 of the top 40 ideas came from the computer. It wasn’t even close!

I think there’s this fear out there among creative people that the value of their creative output could be reduced by artificial intelligence. And that experiment itself demonstrates that those students’ ideas were less valuable than the AI’s output. So I wonder how you’d speak to the anxieties that people have about AI infringing on human creativity.

I respect that concern. But I believe that AI will amplify our creativity, rather than replace it. The most creative people I know are learning how to use generative AI to come up with new ideas.

One thing they didn’t test at Wharton was having humans and AI working together. I think that the combination will yield the best ideas.

To paraphrase Edison, creativity is 1 percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration. Generative AI may help us generate ideas, but it’s not so good at ranking them and figuring out what’s most interesting or practical.

There’s always this fear that the robots are going to take over and become our overlords. I’m not worried about that. A robot is another tool in a long line of tools. Did Photoshop replace all the graphic designers? No. It made them better! Did spreadsheets make accountants obsolete? No.

What is important is to accept AI as a new instrument and not to fear it. When a musician encounters a new musical instrument, do they say, “This is the end of music”? No. They say, “What can I play with this? Let’s jam with it!”

Writers for films and TV are worried, but generative AI hasn’t come up with any really funny jokes yet.

Are there any generative AI tools out there that you’re particularly excited about?

I like DALL-E, OpenAI’s tool for generating images. It’s a different kind of system that uses a method called diffusion networks to generate astounding images. There are now systems that generate video and three-dimensional objects.

I also like Pi. It’s a conversational agent based on a large language model. But it’s tuned to actively ask questions to create and sustain conversations. It’s like talking with an extremely engaging, well-informed person who never gets tired!

That immediately makes me think of the movie Her, or some kind of AI companion.

I agree, there’s something disturbing about this. In the film, Joaquin’s character was a pathologically lonely person. In China, there was a chatbox, Xiaoice, that many people became addicted to. They would talk to it on the long train ride home from monotonous jobs.

But the new generation of chatbots like Pi could be used by senior citizens—I’m going to be one very soon. It could conceivably be a very well-informed, attentive, and entertaining companion. What’s so terrible about that?

What we need to remember is that this is a different type of intelligence. It’s not human intelligence.

Or a replacement for humanity.

Exactly. Let’s talk about replacement theory. There is a deep-seated fear of the unfamiliar, that some foreigner is coming to steal jobs. That’s what they said about the Chinese, the Polish, the Irish, and the Jews. People who are insecure are looking for a scapegoat.

I read somewhere that you referred to it as a kind of xenophobia.

Yes, the fear of robots seems xenophobic. Robots and AI are the “other” that many people fear.

How would you make the optimistic case for the future of AI as it relates to art and creativity?

One realm that comes to mind is Hollywood. The writers were on strike. I was invited to an online meeting to talk about the risks of AI. Most writers were confident that AI needs to be stopped. I asked, “How many of you have played with it?” Silence. They said they don’t want to play with it because that will help it get better. I was shocked.

It’s just the opposite. AI can help writers get better. Hollywood has been in a rut, just releasing sequels and prequels.

I believe that the best writers spent the strike using ChatGPT to come up with all kinds of really new and exciting stories.

Now that the strike is over, I think we’re going to see lots of these creative ideas. I think it will be a golden age for Hollywood. I think the same is true for academic research. I encourage my students to use it. I’m not afraid to try something that was suggested there. It doesn’t scare me at all.

Can you tell us more about your upcoming Getty installation?

It’s a collaboration with my wife Tiffany Shlain. We will use generative AI to help visitors create historical tributes to trees in their neighborhoods.

In a prior interview you said that you didn’t view robots as potential collaborators, but more as subjects, at least in your own work. What you’re describing sounds much more along the lines of AI as a collaborator than a subject. Is that fair to say?

I want to be careful where we draw this line. For the Getty project, Tiffany and I are the artists. The idea of using ChatGPT did not come from ChatGPT. So in this case, ChatGPT is a medium, like wood or glass, that we shape and draw on for this project. So I wouldn’t say that it’s a collaborator.

If I seem overly optimistic it’s because I’m trying to counter all the negativity out there.

But you’re right to ask this question. If we had sat down with ChatGPT and said, “OK, I’m going to do an exhibition about trees. What are all the different ways I could express this idea?” and it came up with that idea, well, we might have to give it a creative credit. But we asked the question.

Ultimately, the artist makes the decision about which ideas to accept and how to refine them.

Earlier you talked about your feeling that we’re on the cusp of a boom in creativity—at least in Hollywood. But in terms of the arts in general, do you think generative AI might usher in a creative boom?

Yes. Consider the analogy to the roaring 1920s when there was a boom in creativity and innovation that followed a pandemic. I think that there’s something similar happening now. And AI is part of that story.

If I seem overly optimistic it’s because I’m trying to counter all the negativity out there.

Some thought at the end of the 19th century that all science was finished, that there was no more science to be done. But there’s infinitely many new ideas, artworks, inventions that are waiting to be discovered. That’s my message. Don’t jump to a negative conclusion and retreat. Embrace AI and jam with it.

Editor’s Note: While Professor Goldberg and others are bullish about the promise of AI, many are also warning of potential perils. One of the leading voices of caution is Berkeley computer scientist Stuart Russell, who also happens to be one of the world’s most respected AI researchers, and co-author, with Berkeley alumnus Peter Norvig, Ph.D. ’86, of what is considered to be the most authoritative text on the subject, Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach. More recently, in 2019, Russell published Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control. In the preface to that book, he writes: “Everything civilization has to offer is the product of our intelligence; gaining access to considerably greater intelligence would be the biggest event in human history. The purpose of the book is to explain why it might be the last event in human history and how to make sure that it is not.”

On March 28, California Editor-in-Chief Pat Joseph will be discussing this topic with Professor Russell at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive as part of our California Live! series, where we invite Berkeley’s brightest minds to help us explore the most exciting developments and most pressing issues faced by our rapidly changing world. We look forward to seeing you there.