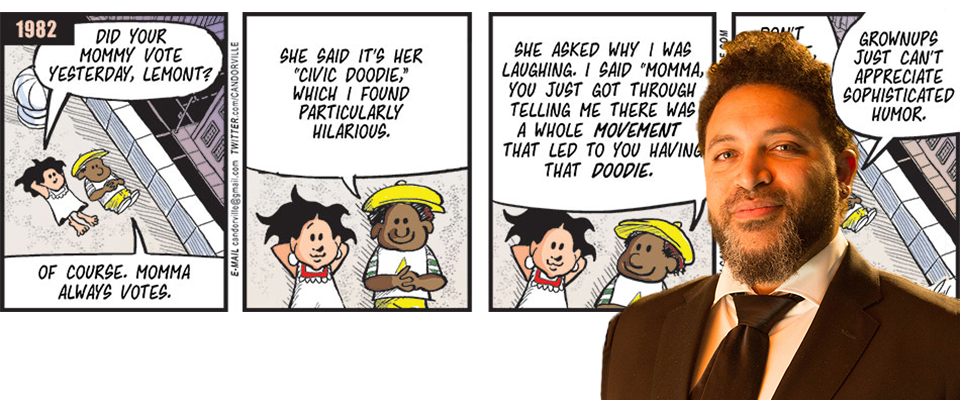

The Talk

By Darrin Bell ’99

Is young Darrin Bell paranoid or is the world out there really racist? That’s the question posed at the outset of the Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist’s excellent new graphic memoir, The Talk.

Early on, Bell’s white mother tells him “white people won’t see you or treat you the way they do little white boys.” That’s why, when he asks for a squirt gun, she buys him a bright green one, so he won’t get shot. By the police.

His father, who’s Black, thinks his ex-wife is paranoid. So does his older brother. But they don’t know about Darrin’s real-life encounter with the LAPD. Him with his squirt gun, the cop’s hand hovering over his holster.

Evidence of racism—some subtle, some not—mounts as Darrin grows. There are the teachers who call him “one of the good ones.” There’s the Berkeley cop who doesn’t believe he and his girlfriend are Cal students. There’s the Cal professor who accuses him, without proof, of plagiarism. There’s Trayvon Martin, and Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. There’s a president who calls Mexican immigrants rapists.

As a (white) reviewer, I admit there were times reading Bell’s book that I thought that maybe he was, in fact, a little paranoid. Or maybe just exaggerating. The scene with the cop and the squirt gun, for example. It seemed unlikely a police officer would be so threatened by a little boy that they’d actually reach for their weapon. And then I remembered Tamir Rice, the 12-year-old boy who was shot dead by police in Ohio in 2014.

He’d been playing with a toy gun.

—P.J.

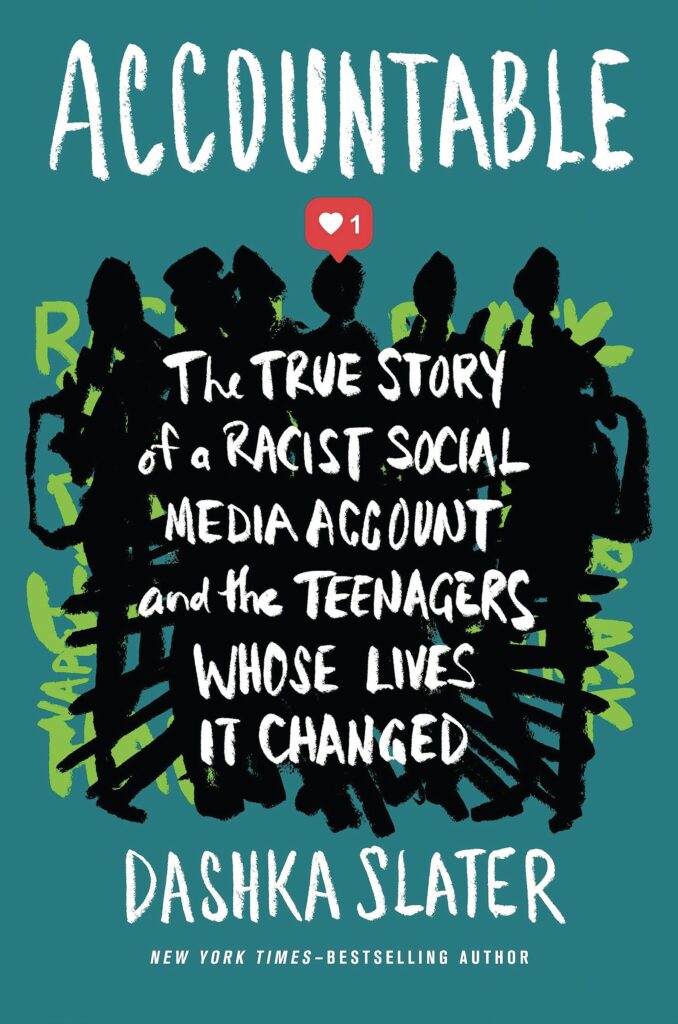

Accountable

By Dashka Slater ’86

In November of 2016, a high school boy in Albany named Charles started a finsta (i.e., fake Instagram account) at the encouragement of friends. It featured typical spam account content—memes and boys making fun of each other—but at least half of the posts were appallingly racist. Often targeted towards his peers, there were jokes about the KKK, frequent use of the N-word, pictures comparing Black students to gorillas, and nooses drawn around the necks of their Black classmate and a Black faculty member.

Dashka Slater’s Accountable takes readers from the creation of the account to the years-long fallout after it was discovered. She explores how the account affected everyone involved, from the targeted students to the followers to the parents and teachers who tried—and usually failed—to help. This wasn’t an isolated incident: According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, use of racial slurs, bigotry, and harassment of minority children in schools surged during and after Donald Trump’s presidential campaign. Slater, whose previous bestseller, The 57 Bus, traversed similar terrain, grapples with the many complicated questions that emerge, including ones of free speech, accountability, and reconciliation.

—M.C.

Light Places

By LP Giobbi

Self-described DJ, producer, keyboardist, and activist, Giobbi (née Leah Chisholm ’08) wrote most of her debut album, Light Places, between gigs—from the confines of planes, trains, and hotel rooms.

A celebration of her musical journey from jazz pianist to self-taught electronic producer, the album samples everything from Grateful Dead guitar lines to high-profile collaborations with the likes of musical duo Sofi Tukker and singer-songwriter Monogem. A dream about jamming on stage with Jimi Hendrix inspired the driving, drum-heavy track “Georgia,” while a heartfelt voice note from her tour manager’s grandmother became a cinematic, one-minute interlude.

Giobbi, an Oregon native and the child of lifelong Deadheads, studied jazz piano performance at UC Berkeley, playing regular piano gigs in San Francisco before landing an opportunity to move into electronic music production. Since then, she’s carved out a space for herself in the house scene, with her particular mix of piano improvisation and melodic beats.

Giobbi’s album opens on the piano, with a trilling, reverberant rendition of jazz master Bill Evans’s “Peace Piece,” and ends with crowd-sourced recordings of friends singing the Dead’s version of “Not Fade Away.”

—Leah Worthington

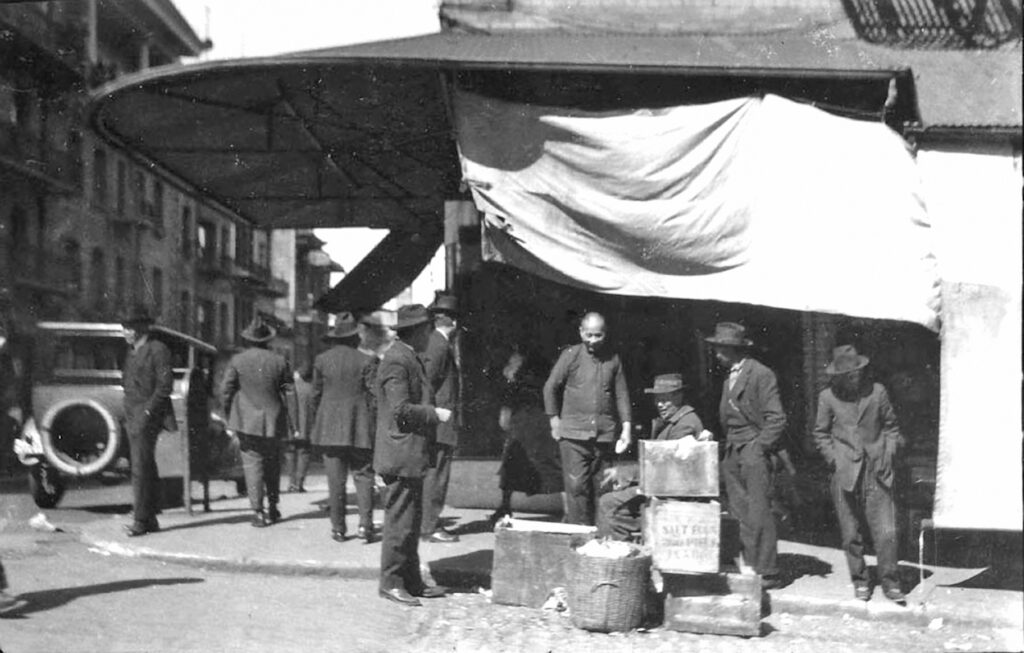

Orphan Bachelors

By Fae Myenne Ng ’78

After her seamstress mother tells her a story about her seafaring father, author and Chinatown native Fae Myenne Ng realized she had been entrusted “with a family story; I was no longer a child.” Likewise, readers of Ng’s memoir about the “orphan bachelors” of her title—a lost generation of men prevented from starting families by the Chinese Exclusion Act—are entrusted with a story as complex and nuanced as a Chinese puzzle box. Raised among these sympathetic men in the new land, Ng records their legacy and the way in which untold suffering resulting from immigration policy is handed down across the generations.

“[The orphan bachelors] called me a mouthy bird, and one by one, they shuffled off, their steps a Chinese American song of everlasting sorrow.”

A recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Ng was nominated for the PEN/Faulkner Award for her first novel, Bone, and won the American Book Award for her second, Steer Toward Rock, both stories of remembrance about San Francisco Chinatown. A practicing artist in the Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies Program at Berkeley, Ng emphasizes the significance of heritage. “I write about family; I teach my students how to escape theirs, that it’s no crime,” she writes.

—Danielle Shi

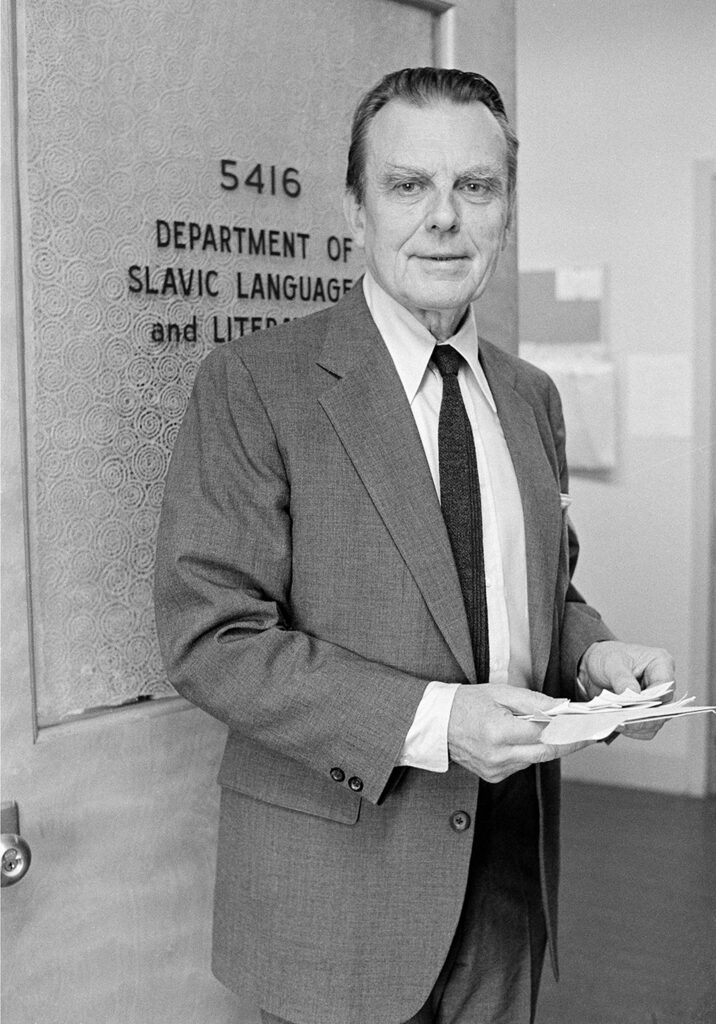

On Czeslaw Milosz

By Eva Hoffman

“I am here. Those three words contain all that can be said—you begin with those words and you return to them.” That is how Czeslaw Milosz began his 1982 book of essays, Visions from San Francisco Bay. “Here” was Berkeley, where Milosz, the celebrated poet, winner of the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature, taught in the Slavic department for decades. He had come to California in exile, an émigré from what he called “the Other Europe”—that is, Eastern Europe, specifically Soviet-controlled Poland and Lithuania. As the line quoted above suggests, he was never quite at home in Berkeley.

In this compact volume, part of a series from Princeton University Press called Writers on Writers, Eva Hoffman appraises Milosz’s work with an unusual level of understanding and empathy. She, too, emigrated from Poland, to Canada, and therefore appreciates both the agony of displacement and its advantages for a writer; namely, an increased “awareness that our familiar world, our versions of personality, our deepest assumptions about existence, are not the only version of ‘the human.’”

—P.J.

Bottoms

Marshawn Lynch

Former Cal and NFL star running back Marshawn Lynch turns in a surprisingly charming performance in Bottoms, the raunchy high school lesbian comedy that premiered in August. Lynch plays Mr. G, an oblivious teacher who finds himself as the advisor for a fight club started by PJ and Josie, two “ugly, untalented gays” (in their own principal’s words) who hope to use the club (marketed as a self-defense class to empower women) to attract the cheerleaders they are in lust with. Mr. G, an oversharer about his own impending divorce, is airheaded but supportive.

When director Emma Seligman first reached out to Lynch for the part, he didn’t immediately jump at it. “He was like, ‘Do you have me confused with someone else? Like an actor?’” Seligman told GQ. The former Cal tailback may be better known for his Beast Mode style of football and stonewalling the sporting press, but the New Yorker considers him a screen veteran as well, after appearances in such shows as Brooklyn Nine-Nine, The League, and Westworld. Ultimately, the Oakland native says he took the role to honor his sister, whose sexual orientation he initially had difficulty accepting. He has come to fully support her, even walking her down the aisle at her wedding.

—M.C.

credit: MGM/YouTube

The Unnaming of Kroeber Hall

By Andrew Garrett

In this new book from MIT Press, Berkeley linguist Andrew Garrett, whose academic work focuses on California Indigenous languages, examines the question of how his predecessor in the field, Alfred Kroeber, came to be denounced as racist by the institution he devoted his life to and had his name stripped from the campus anthropology building.

A racist, Kroeber was not, Garrett insists. To the contrary, “in both academic and popular work, Kroeber argued forcefully against contemporary racism and eugenics; he collaborated with Indigenous scholars and uplifted their work, and advocated for Native cultural and land rights.”

Nevertheless, Garrett believes the decision to remove the Kroeber name was ultimately the correct one, due mostly to the fraught legacy of so-called salvage anthropology.

“The specific claims about Kroeber’s work offered in support of unnaming Kroeber Hall, accepted by many at Berkeley and beyond, are erroneous or unsubstantiated,” he writes. “Yet the actions, choices, and words of anthropologists and linguists over more than twelve decades have led to harm, including understandable anger and pain for many people, especially Indigenous people, both within and outside the academy.”

To sum up Garrett’s position: Unnaming Kroeber Hall was the right decision, made for all the wrong reasons.

—P.J.

The Rite of Spring/common ground[s]

Cal Performances

When Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, the story of winter brought to a close through ritual human sacrifice, first premiered in Paris in 1913, many of the audience members were outraged. But it subsequently became one of the most important pieces of art of the 20th century. The German modern dance choreographer Pina Bausch’s 1975 version of the ballet comes to Cal Performances in February, joining a series of performances in the 2023–24 season with the theme of “individual and community.” The Rite of Spring is a grim example of weighing an individual’s needs against that of a community, says Cal Performances executive and artistic director Jeremy Geffen.

This is the first time Bausch’s production has come to Cal Performances, and instead of being performed by her dance company as it has been for more than 40 years, this Rite of Spring is a collaboration of the Pina Bausch Foundation (run by her son, Salomon Bausch); a dance school in Senegal, École des Sables; and the Sadler’s Wells dance organization in London. It features 36 dancers from 14 African countries, and it’s on a double bill with common ground[s], a duet co-created and performed by two septuagenarians, Germaine Acogny and Malou Airaudo.

Geffen started the Illuminations series when he joined Cal Performances in 2019. Each season, the series features programming around a theme that Berkeley professors and researchers examine along with the artists performing on the Zellerbach stage. Geffen felt that this was an ideal way to look at pressing issues—and would give audiences access to the groundbreaking thinkers at a world-class public research institution. This year’s theme of “individual and community” is explored in eight different performances. For the full 2023–24 program, visit calperformances.org.

—Emily Wilson