Legendary blues musician Taj Mahal (real name Henry St. Claire Fredericks Jr.) was once asked by National Public Radio what drew him to settle in Berkeley. The Grammy-winner answered: “The weather, the mix of people. The university was in the middle, the ideas were there, the sound of the music was coming out of everywhere, and all kinds of it.”

Great universities, and great cities, are like that; they exert a kind of social gravity that draws talent into their orbit. Creative communities cluster around them like galaxies.

While music may not be the first thing most people think of when they think of Berkeley, both the campus and town have been home to an enormously influential and eclectic music scene across the years, one with deep roots in the folk and blues revivals of the mid-20th century.

With streaming media making a world of music instantly available to nearly all of us all the time—a kind of worldwide jukebox, if you will—we decided to create a playlist to help tell the story of the music that influenced Berkeley and how Berkeley, in turn, influenced American music.

Read on. And while you do, by all means listen. You can listen to our Berkeley Jukebox playlist on Spotify.

TRACK 1

Midnight Special

Lead Belly

Back in the late 1950s, there was a show on KPFA called The Midnight Special that aired live folk music from 11 to midnight on Saturdays, produced and hosted for a time by Berkeley student Barry Olivier. The show was later helmed by the wonderfully named Gert Chiarito, who welcomed all comers to the studio. “Didn’t matter how bad they were,” she said. “At that time of the night, who cared?” In fact, many were excellent. Local and touring musicians, sometimes as many as ten at a time, would drop by the station to perform songs. They’d close the program by singing “Midnight Special” together. While Lead Belly’s version is perhaps the best known, its origins are lost in the mists of time. Like all true folk songs, it’s the property of no one and everyone.

TRACK 2

Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You

Joan Baez

It was on The Midnight Special, sometime around 1959, that Anne Bredon ’60, M.A. ’63, then Anne Johannsen, played a song she wrote called “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You.” Bredon was a student at Cal at the time, studying math. When she sang her folk lament (listen here), it sounded haunted and unsentimental, a dry-eyed dirge for doomed love. Another performer on the show, Janet Smith, who also attended Cal, learned the song and later played her own version at a hootenanny in Oberlin, Ohio, which is where Joan Baez first heard it. Baez, then the undisputed queen of folk, liked it so much she made it the first song on her first live album, in 1962. To her, it sounded like a traditional folk song, and that’s how it was credited: Traditional, Arr. Baez.

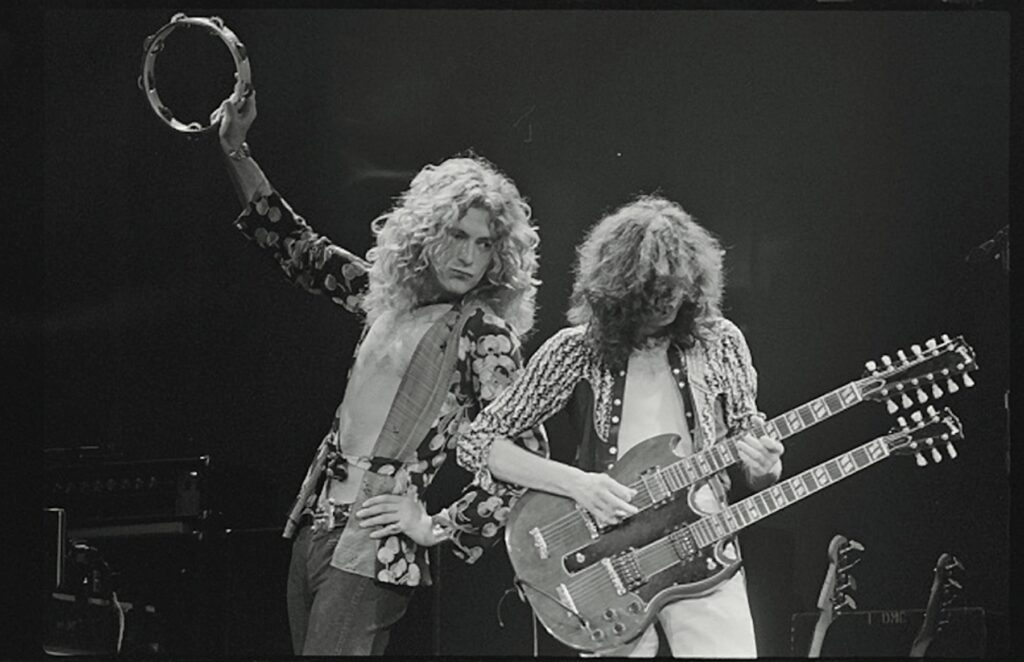

TRACK 3

Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You

Led Zeppelin

Jump ahead to the year 1968 and a boathouse on the River Thames owned by guitarist Jimmy Page, who is just getting to know a young Robert Plant, a singer he’s hoping to try out for his new, not-yet-named rock band. Plant flips through Page’s record collection and pulls out the album Joan Baez in Concert. “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You” is one of the first songs they bond over and one of the first they record as Led Zeppelin. The lads’ baroque version is at times very, very heavy and also very light, like their name. And despite the all-female conduit (Bredon-Smith-Baez) that has brought it to them, it now fairly drips with testosterone. They too credit the song as traditional, this time arrangement by Page. Only much later will the heavy metal version come to the attention of Bredon, who is subsequently given both proper credit and back payment.

TRACK 4

Dark Star

The Grateful Dead

One of the volunteer technicians on The Midnight Special was a gawky Cal dropout named Phil Lesh, who sometime in the year 1962 brought Chiarito a demo tape he made of his 19-year-old friend from Palo Alto, Jerry Garcia, on guitar. Chiarito thought he was so good she devoted a whole show to him. Lesh, who was more into avant-garde classical music at the time, turned out to be a wizard on bass, and the duo subsequently joined talents in The Grateful Dead, bringing the world acid rock, tie-dye, and—sorry, Deadheads—some of the worst dancing known to man.

TRACK 5

To Lay Me Down

Jerry Garcia (Remix) LP Giobbi

Want to hear a new spin on the Dead, one that’s a lot more danceable? Cal alum Leah Chisholm ’08, alias LP Giobbi, a jazz pianist/house DJ, grew up the daughter of Deadheads. Lately, she has started remixing musicians from Taylor Swift to “Uncle Jerry.” Some Deadheads reportedly despise the stuff, but have a listen. You just might dig it.

TRACK 6

San Francisco Bay Blues

Jesse Fuller

Even before the Newport Folk Festival, there was a Berkeley Folk Music Festival. The organizer was Berkeley native and former Cal student Barry Olivier, who ran the show from 1958 to 1970.

The festival took place on the Berkeley campus and featured both large concerts, at venues like the Greek and Pauley Ballroom, and smaller performances and workshops that spilled across the university grounds. Musical guests ran the gamut from Deep South bluesmen like Mississippi John Hurt to white folkie stalwarts like Pete Seeger (whose father, Charles, had once been head of the music program at Berkeley). Over time the festival became even more eclectic and progressive, with the addition of rock acts like Jefferson Airplane and experimental ones like Red Crayola. The latter pushed the boundaries a bit far even for Berkeley, and got Olivier booed.

A local favorite and the headliner of the 1968 festival was Oakland’s Jesse Fuller, a one-man-band whose harmonica brace is said to have inspired Bob Dylan’s own. Fuller also invented his own unique instrument, a pedal-controlled bass viol called the fotdella. Fuller’s “San Francisco Bay Blues,” which features a kazoo solo, was covered by artists ranging from Peter, Paul and Mary to Eric Clapton—thankfully, with the kazoo included.

TRACK 7

Orphan Girl

Emmylou Harris

If the Berkeley Folk Music Festival has a direct spiritual heir, it has to be Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, Warren Hellman’s free music festival in Golden Gate Park, which the billionaire and Berkeley alum (’55) bankrolled in perpetuity. Originally, it was called Strictly Bluegrass. As Hellman once recalled in these pages, “Emmylou [Harris] agreed to come the first year, and I really wanted her to play bluegrass.… I thought if I called it Strictly Bluegrass she would be shamed into it. But no. We tried it again the next year: No. So we changed the name to Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, and as soon as we did, Emmylou started playing bluegrass.”

Harris has closed the festival every year since 2001.

TRACK 8

Deep Ellum Blues

The Wronglers

After Hellman died, in 2011, his extended family, including daughter and Berkeley physicist Frances Hellman, formed the Go To Hell Man Band, now also an annual fixture at the festival. Warren, too, performed at his own festival, on banjo, with his band, The Wronglers. On this track, they’re with Jimmie Dale Gilmore putting a little bluegrass feel into the traditional “Deep Ellum Blues.”

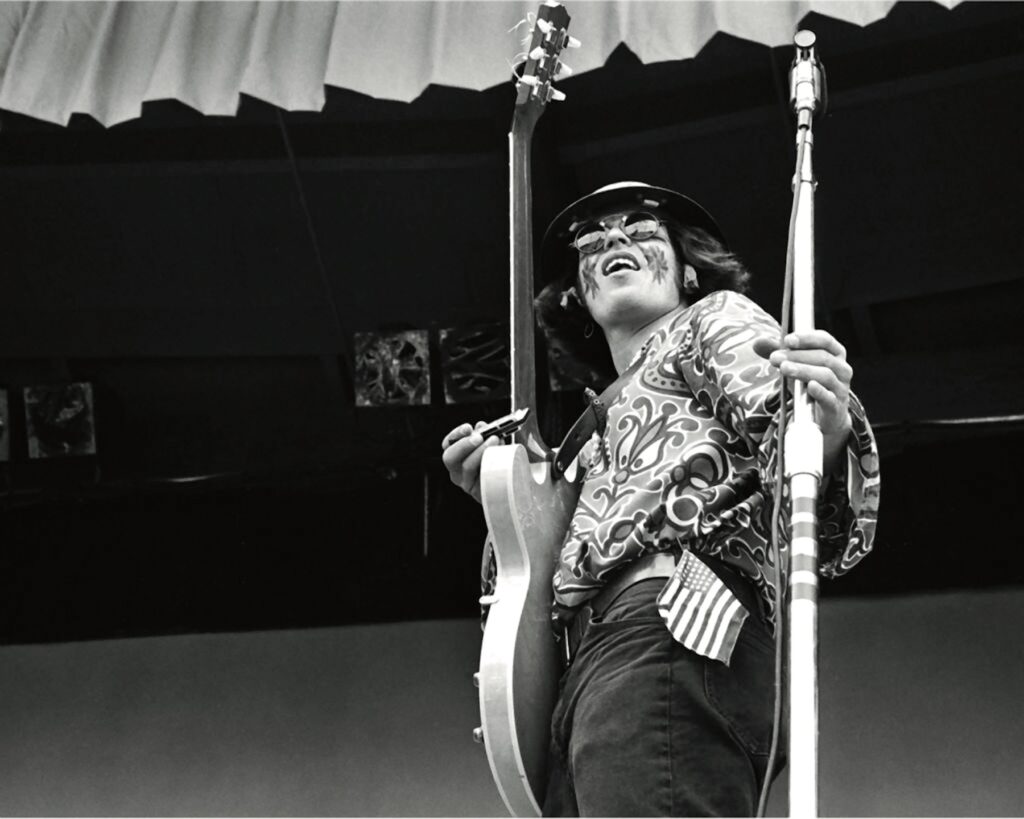

TRACK 9

Lodi

Creedence Clearwater Revival

Perhaps the most famous local talent fostered by the Berkeley music scene was John Fogerty, lead singer of Creedence Clearwater Revival, who took guitar lessons from the aforementioned Barry Olivier and attended the Berkeley Folk Music Festival as a youngster with his mom. As he writes in his autobiography, “these weren’t just concerts: they were an education. I was enthralled by the whole thing. These folk festivals were hugely rewarding—just bedrock for me. And not just musically. I’m certain that folk music has a lot to do with my entire belief system in terms of how the world should work.” It also goes a long way to explaining how a kid from El Cerrito came to sing so convincingly about them ol’ cotton fields back home and being born on the bayou. Few of CCR’s songs are set outside the mythic South, let alone in California. “Green River,” putatively about Putah Creek, is one. “Lodi,” about a down-and-out country singer in the Central Valley, is another.

TRACK 10

I’m Coming Home

Clifton Chenier

Clifton Chenier really was born on the bayou, in Opelousas, Louisiana. The so-called King of Zydeco was rescued from relative obscurity by Berkeley alumnus Chris Strachwitz ’58, Cert.Ed. ’59, a German immigrant turned obsessive American music collector who elevated the profile of hundreds of roots musicians with his El Cerrito–based record label, Arhoolie. Strachwitz’s vast catalog of recordings, now part of the Smithsonian Folkways collection, inspired mainstream artists from Bonnie Raitt to the Rolling Stones.

Chenier won a Lifetime Achievement Grammy in 2014, and his friend Strachwitz recalled their first meeting at “a tiny beer joint” in Houston in 1964. “There was this lanky black man with a huge piano accordion on his chest singing the most low-down blues in a strange patois for a small dancing audience. This was Clifton Chenier, and I was totally enthralled by his totally unique Creole music.”

TRACK 11

I-Feel-Like-I’m-Fixin’-to-Die Rag

Country Joe McDonald

Few songs are as closely associated with Berkeley as Country Joe McDonald’s anti-Vietnam song, the one that starts “One…two…three, what are we fighting for?” It was first hastily recorded in 1965 in the living room of Chris Strachwitz, who managed to keep the rights. As he later explained on the Kitchen Sisters podcast: “As they walked out, [Joe] asked me, ‘What do we owe you for the tape, Chris?’ and I said, ‘You don’t owe me nothing.’ I asked them, ‘Can I have the song for my newly formed [music company]?’ He said, ‘Go ahead, do that!’ It was a verbal agreement. Some years ago, Country Joe came to me and he said, ‘Chris, don’t you think you made enough money off of me by now?’ I said, ‘Yeah, OK, Joe, you’re a good socialist. If you want it back, I’ll give it back to you.’”

Ironically, McDonald would later be sued by the heirs of New Orleans bandleader Kid Ory, who claimed the tune was a rip-off of Ory’s 1926 ragtime number, “Muskrat Ramble.” The court ruled for McDonald.

TRACK 12

Little Boxes

Malvina Reynolds

Joe McDonald was hardly the only one in Berkeley penning protest songs. Malvina Reynolds, known as “The Singing Grandmother,” scored a hit with her slam on the suburbs and middle-class conformity. Despite holding a doctorate in English from Berkeley (’25, M.A. ’27, Ph.D. ’39), she didn’t spare higher ed, either.

And the people in the houses

All went to the university

Where they were put in boxes

And they came out all the same

Written in reaction to the tract housing on the hillsides of Daly City, “Little Boxes” gave the world the neologism “ticky tacky” to mean cheap crap. Covered by at least 37 different artists, from Angelique Kidjo to Randy Newman and Elvis Costello, the song gained new popularity as the intro theme to the Showtime comedy Weeds.

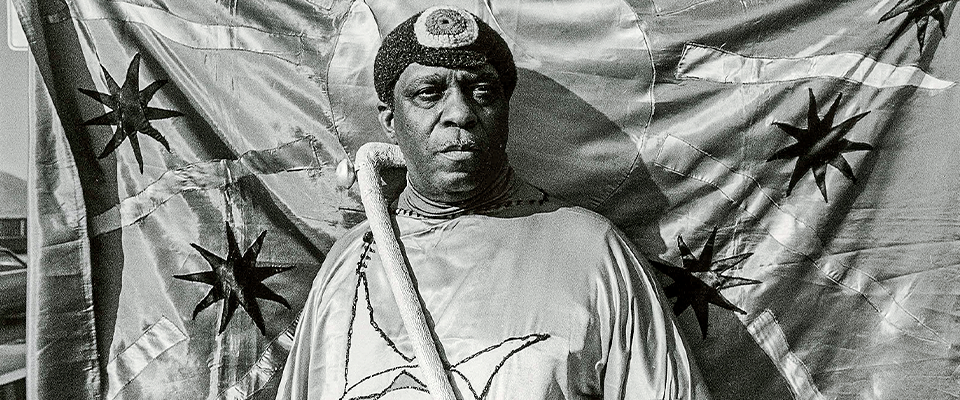

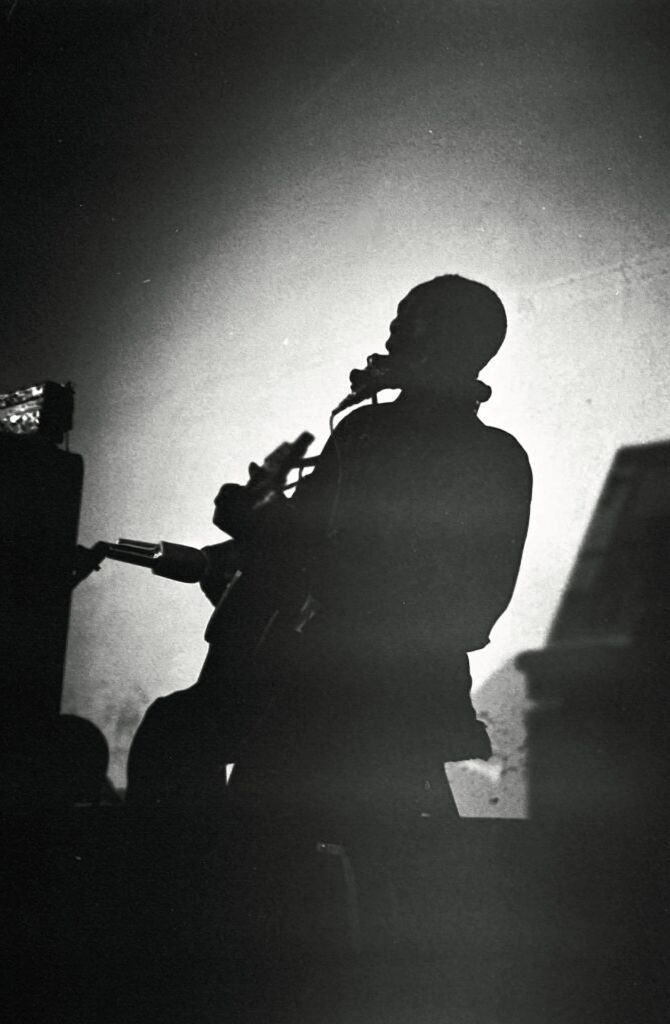

TRACK 13

Make Another Mistake

Sun Ra

It wasn’t all folk music on the Cal campus. Berkeley had blues and jazz festivals too, featuring stars like Big Mama Thornton and Miles Davis. Jazz orchestra leader Sun Ra even taught a course at Cal for a semester in 1971, called “The Black Man in the Cosmos.” Long before the term Afrofuturism was a thing, Ra, who insisted he was from Saturn, not Birmingham, Alabama, was exploring new sonic frontiers while writing an alternate vision for Black identity. “History is only his story,” Ra said. “You haven’t heard my story yet. … [M]y story is endless.” This song is a chant, one that could serve as a mantra for creative people everywhere, about the necessity of failure. “You made a mistake. / You did something wrong. / Now make another mistake / and do something right.”

TRACK 14

Festival

Chuck Berry

Elvis may have left the building, and Sun Ra may have been from Saturn, but Chuck Berry, who played the Berkeley Blues Festival in 1965, has left the solar system—his music has, anyway, launched into outer space aboard NASA’s Voyager probe. Berkeley journalism professor, science journalist, and Rolling Stone editor Timothy Ferris worked with astronomer Carl Sagan, musicologist Alan Lomax, and others to put together the playlist for the legendary Golden Record. Lomax adamantly opposed putting Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” in the mix with Bach concertos and Navajo night chants. Rock ’n’ roll, he groused, was an “adolescent” art form. To which Sagan reportedly responded, “There are a lot of adolescents on the planet!”

Hail, hail, rock ’n’ roll!

TRACK 15

What’s Going On

Marvin Gaye

Here’s one I bet you didn’t know about. I know I didn’t. Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” was inspired by the police brutality at People’s Park in Berkeley in 1969, as witnessed by Obie Benson of the Detroit vocal quartet Four Tops. Benson related the story of Bloody Thursday to his friend and Motown songwriter Al Cleveland, who helped put it to music. The Four Tops didn’t want to do protest songs, so Benson took it to Gaye, who was then transitioning into a new, more socially conscious phase of his career. Gaye reworked the melody and lyrics to his liking. In his book 33 Revolutions per Minute, Dorian Lynskey quotes Benson saying that Gaye “added some things that were more ghetto, more natural, which made it seem more like a story than a song…. We measured him for the suit and he tailored the hell out of it.”

TRACK 16

Ain’t That Peculiar

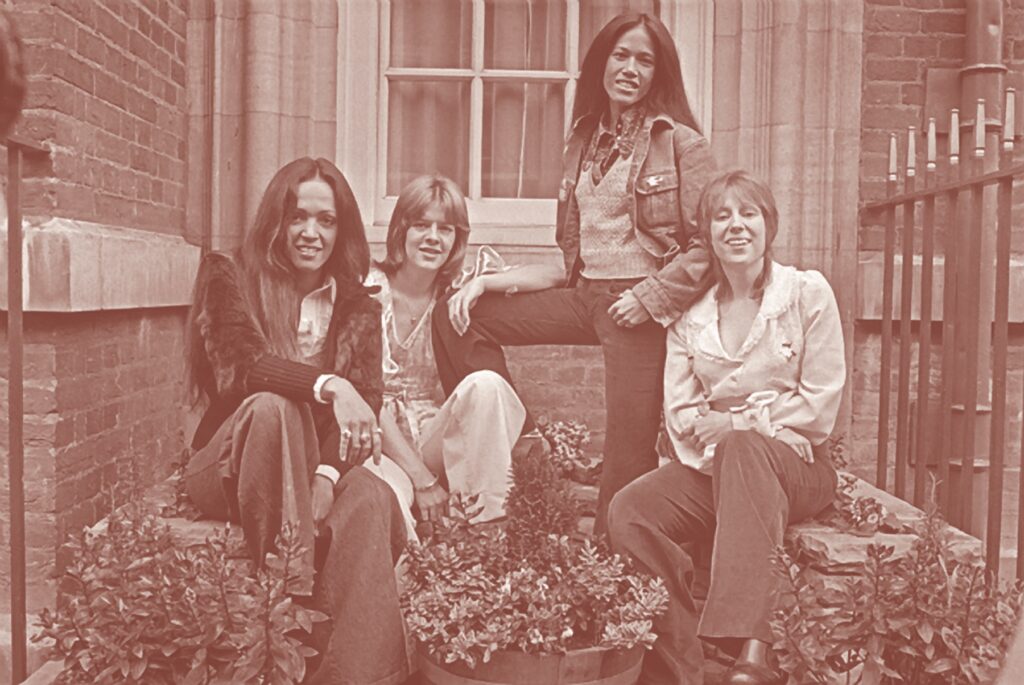

Fanny

Of course, tailoring is what artists do. It’s what Susanna Hoffs ’80 and the Bangles did when their admirer Prince gave them the song “Manic Monday.” As Hoffs told NPR, “That’s one thing that we Bangles decided en masse … we wanted to kind of make it ours—Bangle-fy it, in a sense.” The Bangles were notable for being one of the first all-female rock bands to top the charts. But others had blazed the path, including the psychedelic group Ace of Cups, featuring FSM veteran and Merry Prankster Denise Kaufman on guitar and harmonica. And then there was Fanny, the first all-female rock band to sign with a major label, led by Berkeley dropout June Millington on guitar and vocals. As you’ll hear, when Fanny covered Gaye’s “Ain’t That Peculiar,” they made it their own—Fanny-fied it, in a sense.

TRACK 17

Crosseyed and Painless

Talking Heads

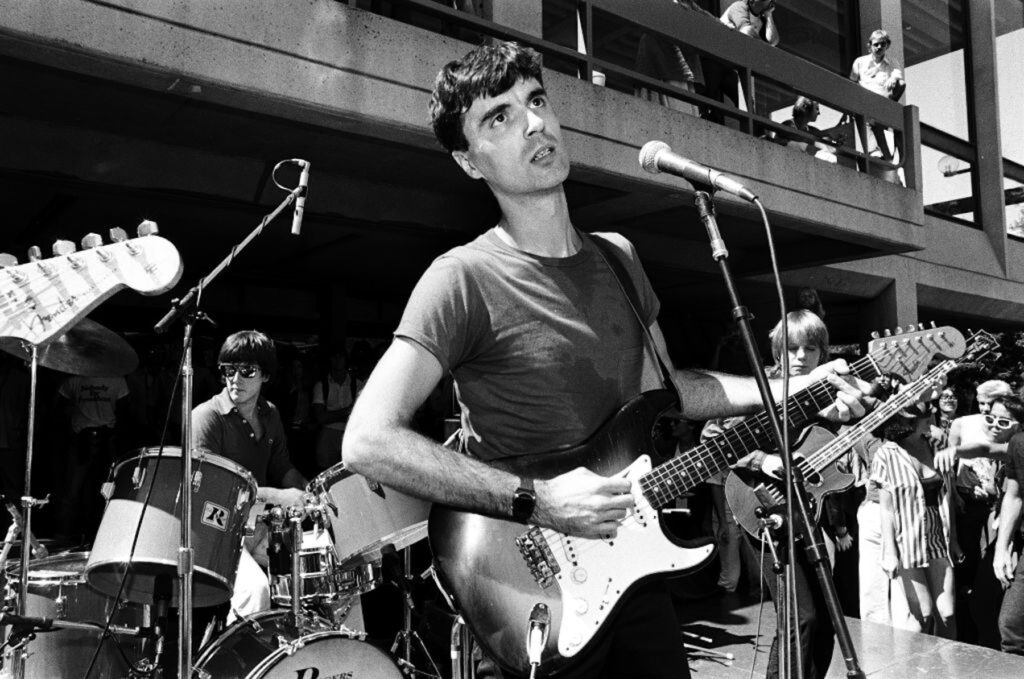

You know the expression “Weird finds a way”? Well, in art, sometimes weird is the way. That’s something David Byrne appears to have learned early on, in Berkeley. As the Talking Heads frontman recalls in his book How Music Works, “As twitchy and Aspergery a stage presence as I was in those days, I had a sense from my time busking in Berkeley and elsewhere that I could hold an audience’s attention.”

Talking Heads may be most closely associated with Rhode Island School of Design, where Byrne, drummer Chris Frantz, and bassist Tina Weymouth all studied, but Berkeley clearly had an influence. Not only did Byrne spend time busking on Telegraph, but Talking Heads played Cal’s Sproul Plaza way back in 1978 and the Greek in 1983 on the Stop Making Sense tour. In case you haven’t heard, A24 has brought Jonathan Demme’s incomparable concert film from that tour to theaters, newly remastered in 4K. Otherwise, same as it ever was.

TRACK 18

Driven to Tears

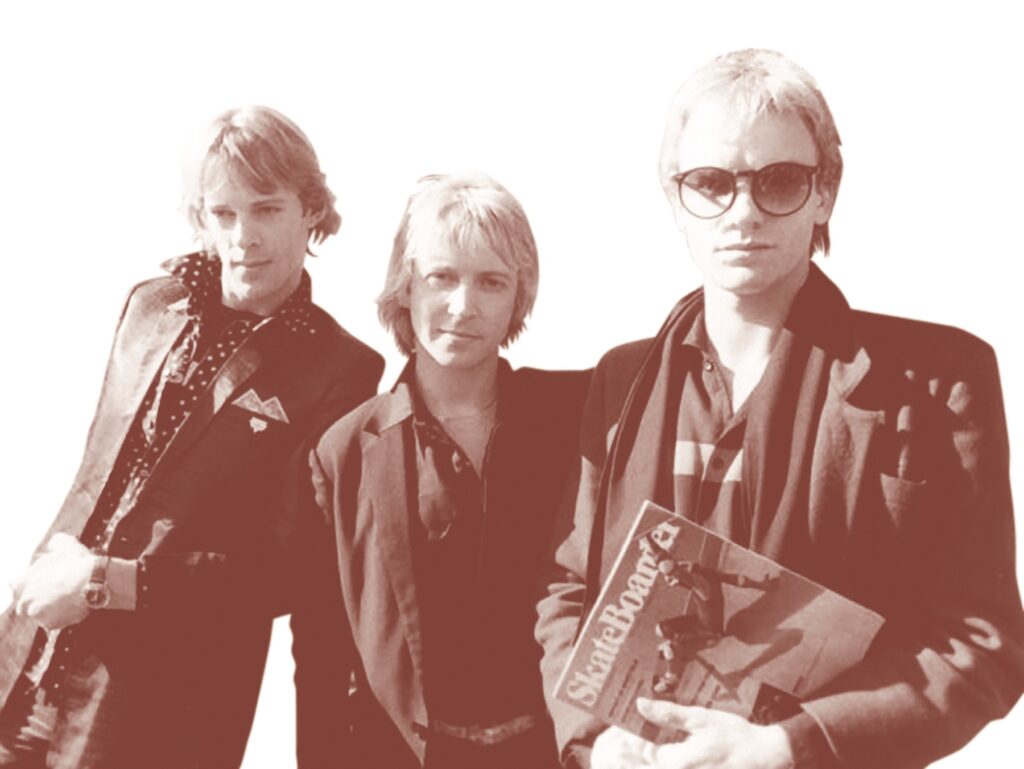

The Police

Stewart Copeland, drummer for and founder of The Police, went to Berkeley. I know, hard to believe. But he did. A self-described diplo-brat (his dad was CIA) who grew up mostly in the Middle East, Copeland came to Cal to major in music but couldn’t meet the admission requirements. Instead, he studied communications and public policy and put his energy into publishing a music business tip sheet called College Event. “If I had gotten into the music department at Berkeley, I’d probably be a timpanist in an orchestra right now,” Copeland later quipped. In “Driven to Tears,” the percussionist shows off his remarkable talents on the drum kit and the Sting-penned lyrics still sting.

TRACK 19

In the Pines

Fantastic Negrito

Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, known on stage as Fantastic Negrito, won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Blues Album in 2017 for The Last Days of Oakland. But it was at Cal that he first learned to play an instrument—not as a student, but on the sly, sneaking into the practice rooms in the music building. “I really loved the hardcore alternative vibe Prince had on Dirty Mind,” he told a reporter, “so I thought, ‘How did Prince learn?’ Well, he taught himself, so I just listened to kids practicing scales, and that was how I learned to play.”

TRACK 20

A Long December

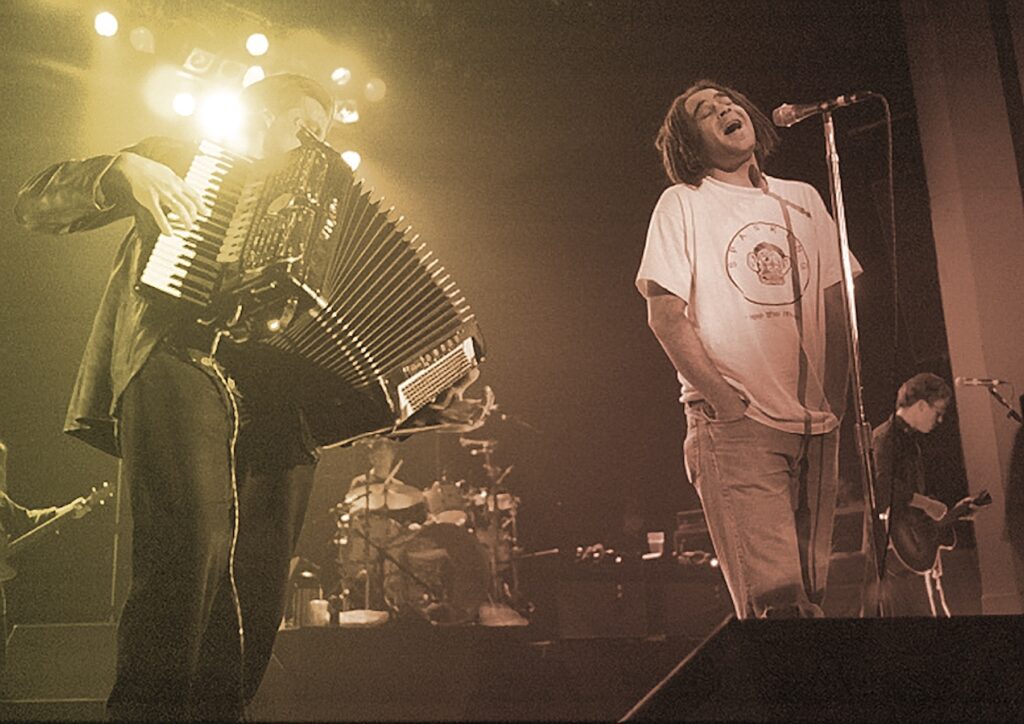

Counting Crows

Of course, we can’t leave this list without a track from homespun roots rock band Counting Crows. Formed in Berkeley in the early ’90s and headed up by Cal superfan and former student Adam Duritz, the Crows played the Greek as recently as September. This song, just right for the season, captures the strange melancholy of California winter and the hope the new year inevitably brings. The song also features Charlie Gillingham, also a former Cal student, on accordion.

TRACK 21

Take My True Love by the Hand

The Limeliters

Quaint though it may seem, this whistling Western ballad has more than 4.5 million listens on Spotify! That’s what happens, I guess, when a song gets included on an episode of Breaking Bad. (Fans of the show, think Walt rolling a barrel full of cash across the desert near the end of Season 5.) Back in the day, the Limeliters were a popular folk threesome, headed up by Berkeley Ph.D. Lou Gottlieb, M.A. ’51, Ph.D. ’58, who played the stand-up bass and provided comic banter to the sophisticates at swank nightclubs like San Francisco’s hungry i. Gottlieb would drop out of the music scene for a time in the sixties and found the famed open-to-all hippie commune Morning Star Ranch in Sonoma. He said he envisioned it as a “pilot study, if you will, for a society in which leisure will be compulsory” due to the “snowballing advance of cybernation, the use of computers in industry.” Gottlieb later returned to the stage but also, ultimately, to Morning Star, where he reportedly spent his last years playing piano in a shack with no electricity. Bet he sounded great.

And that’s it. As the song says, goodbye to everyone. Hope you enjoyed the playlist! Feel free to send us your remarks and recommendations to californiamag@alumni.berkeley.edu. Put “Jukebox” in the subject line.