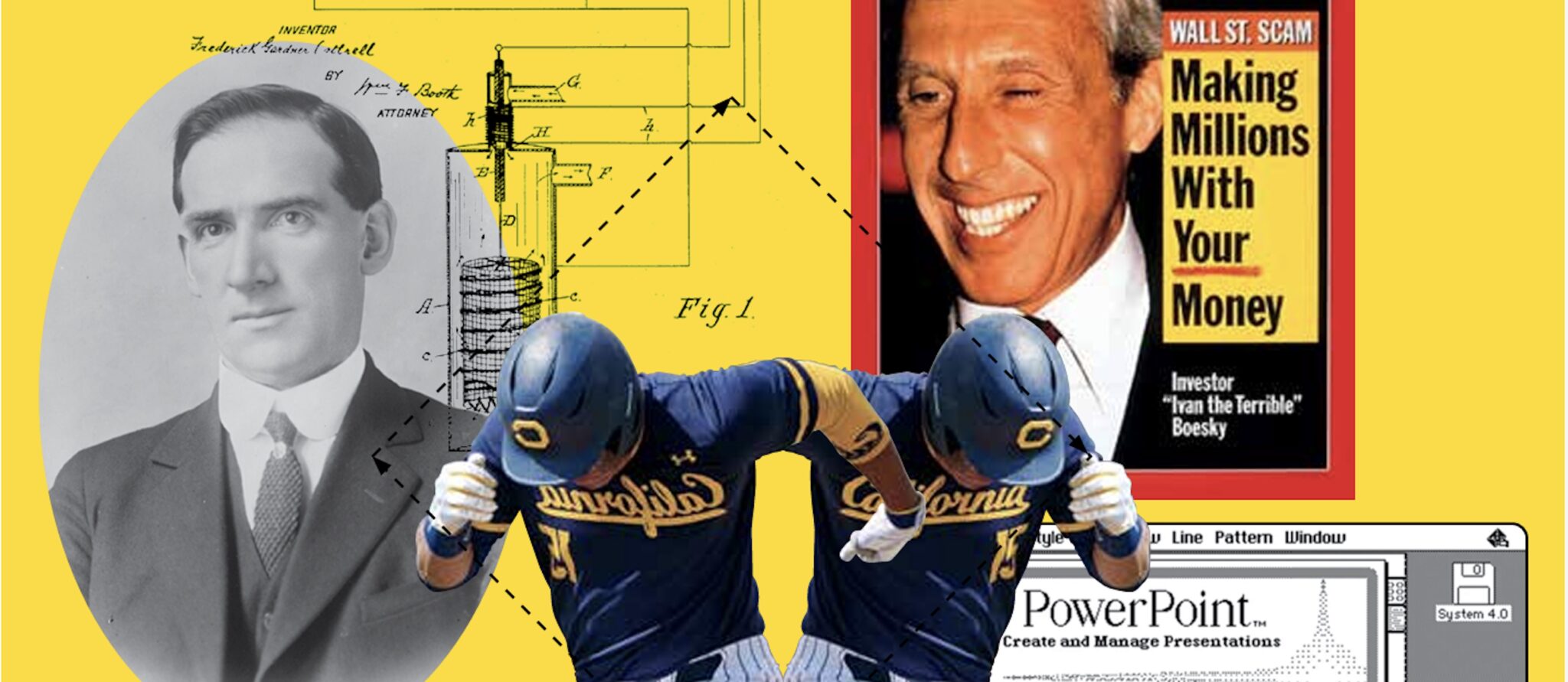

Smokestack Scrubber

Early in the 20th century, as heavy industry boomed and toxic emissions threatened forests, fields, and rivers, Berkeley alumnus and professor Frederick G. Cottrell invented an apparatus to remove particulate matter from smokestacks. Now generally called a Cottrell, the eponymous device is more properly called an electrostatic precipitator and is still very much in use. As you might imagine, the patent on the invention was worth a fortune. Rather than line his pockets, though, Cottrell used the money to found the still extant Research Corporation for Science Advancement, a philanthropic body that has supported the work of scientists, including 44 Nobelists. One of those was E.O. Lawrence, who needed the RCSA’s support to build his 27-inch cyclotron.

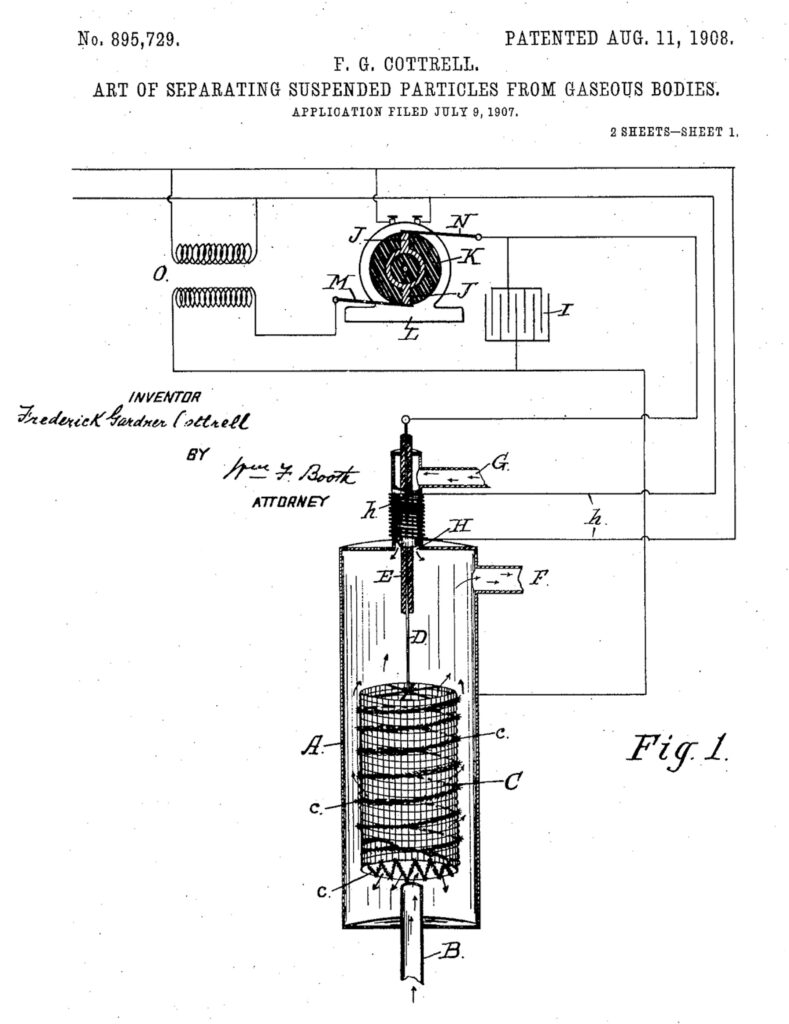

Curb Cuts

Those scoops out of the sidewalk at intersections? Those are there because of the efforts of a pioneering group of disabled student activists at UC Berkeley who called themselves “The Rolling Quads.” While curb cuts are now required under the Americans with Disabilities Act, Berkeley was the first city to implement them on a wide scale, starting in the early ’70s on Telegraph and Shattuck.

The Votomatic

Berkeley political scientist Joseph P. Harris first started tinkering with the idea of an automated vote counting machine in the 1930s but didn’t bring it to fruition until the 1960s, then with the aid of mechanical engineering professor William Rouverol, M.A. ’66. The machines, first commercially produced by IBM, used punch cards to tally votes. Harris didn’t live long enough to see the trouble those cards caused in the 2000 Bush vs. Gore presidential contest, when the outcome hung on the infamous “hanging chads.” But Rouverol did. He went on to patent a new, improved Votomatic called the VoteSure and, later, what he called the “Save democracy election system,” which his filing declared “immune to rigging.”

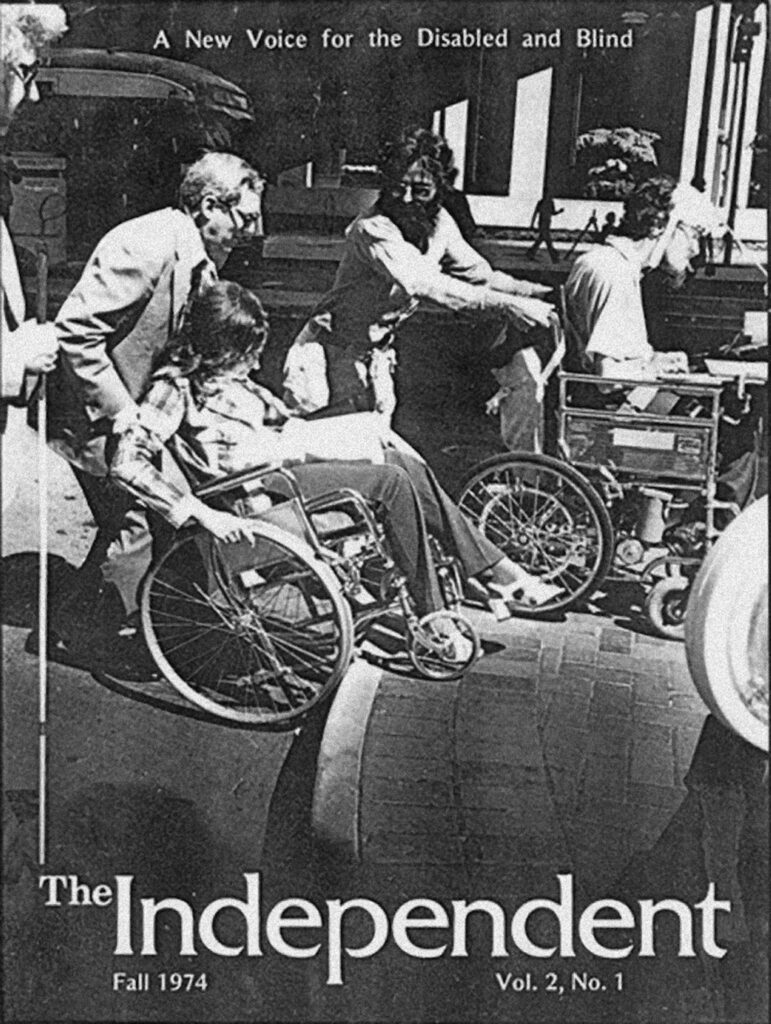

“Greed is Good.”

The Gordon Gekko character’s famous speech in the movie Wall Street was reportedly inspired by remarks that stock trader Ivan Boesky made in his address to the 1986 graduating class of the Haas School of Business. Boesky told the newly minted MBAs, “Greed is all right, by the way. I want you to know that. I think greed is healthy. You can be greedy and still feel good about yourself.” The following year, he was sentenced to three years in prison for insider trading.

Reversible llabesaB

This one came from Berkeley but never caught on. The idea was hatched by Cal baseball coach Carl Zamloch, who, as a noted vaudeville performer, had a flair for showmanship. What baseball lacked, Zamloch thought, was the element of surprise. And so he proposed a simple rule change: Let batters choose to run to first or third after a hit. If the first hitter chose third, the rest of that half-inning would be played in reverse—that is, running bases clockwise. The one and only exhibition game was played on February 15, 1928. The Bears won, and the game drew 500 fans and enormous press interest. The Oakland Tribune called it an “uproarious success.”

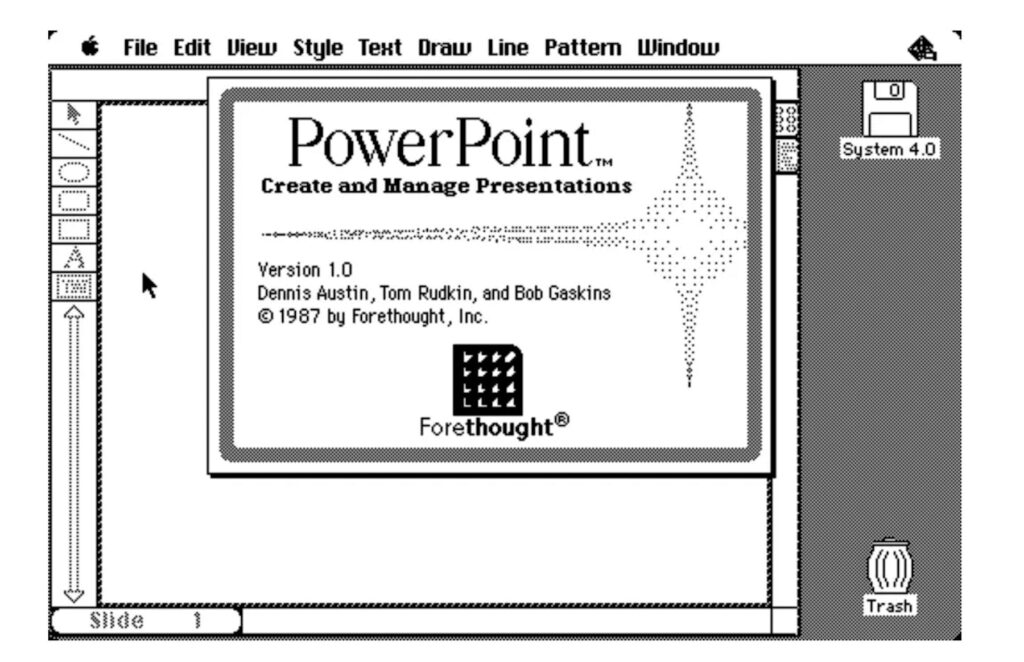

PowerPoint

PowerPoint, the Microsoft presentation software, is now so ubiquitous that it’s hard to imagine it was ever difficult to get the idea off the ground. But in his book Sweating Bullets, PowerPoint inventor Bob Gaskins, M.A. ’73, writes that it was in fact a “desperate struggle” to create “a product that nobody much seemed to understand or appreciate.” First developed in 1987, the software was originally conceived to make overhead transparencies and 35mm slides for carousel projectors. Instead, PowerPoint replaced them entirely with the all-too-familiar digital slide decks.