For the better part of the last 40-plus years, Cal alum and Carnegie Mellon psychology professor Michael Scheier has been thinking about optimism—what it is, where it comes from, and why it matters.

Today, research on mindfulness, emotional well-being, and positive psychology abounds. But that wasn’t the case when Scheier ’70 first started.

Originally, he says, the then-nascent field of health psychology was focused on pathologies—“how stress impacts health,” for example. No one had yet flipped the hypothesis around: If factors like anxiety and depression hurt us, can a positive outlook confer physical benefits?

In the early 1980s, fresh out of graduate school at the University of Texas and wanting to “make a real impact,” he teamed up with fellow social psychologist Charles Carver. Together they posed new questions, like: Could positive thinking breed perseverance? And does optimism promote physical health?

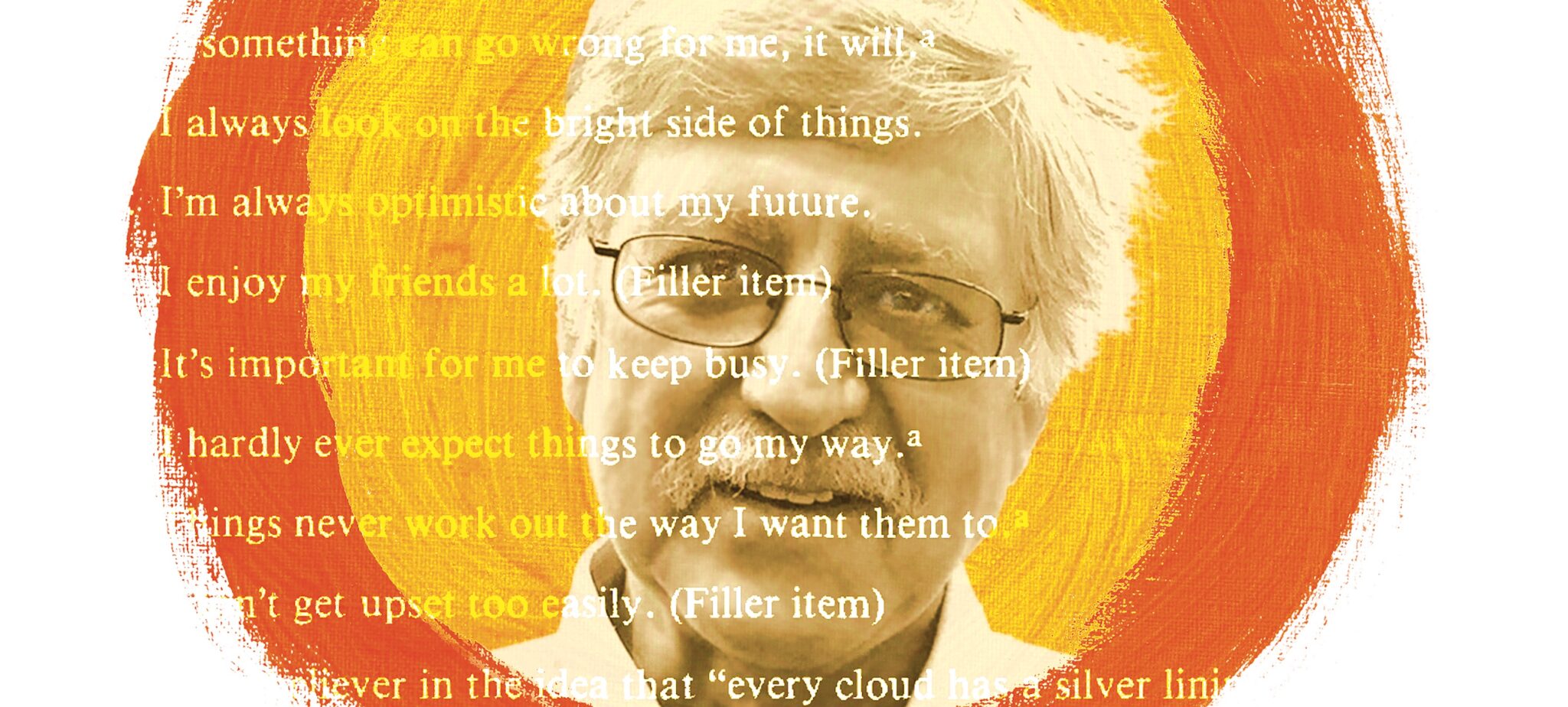

The pair published their seminal paper, “Optimism, Coping, and Health: Assessment and Implications of Generalized Outcome Expectancies,” in Health Psychology in 1985. The study, which has since been cited more than 5,000 times, was an exploration of the positive relationship between optimism and well-being, and the first to offer a method for measuring optimism, also known as the Life Orientation Test (LOT)—a scale that is still used widely today.

In the years since, Scheier has continued to explore the role of optimism in helping people manage stress, cope with major life events, and live healthier, happier lives. Now retired, he mostly steers clear of the press but made an exception for his alma mater. Here he speaks with California about some of the lessons gleaned from his decades of research.

Overall, humanity skews slightly glass-half-full.

There are plenty of reasons to be pessimistic—melting ice caps, school shootings, opioid addiction, etc.—but even so, hope abides.

“If you just measure people, and look at how optimistic and pessimistic they are, the average tends to be a little bit above the neutral point, in a positive direction,” Scheier says. In other words, “a little bit of optimism seems to be the norm.”

You got it from your momma—sort of.

When it comes to having a sunny disposition, genes play a significant role, Scheier says.

Scientists haven’t zeroed in on the genes responsible, but data from studies of twins suggest that an estimated 35 percent of the variation in levels of optimism and pessimism can be attributed to our DNA.

“It’s been a kind of a curse of behavioral genetics for quite a while,” Scheier says. “We have clear evidence that it’s heritable … but we can’t locate the specific polymorphism.”

While the search continues, it’s also true that genetics are outweighed by circumstance. According to Scheier, factors like socioeconomic status (particularly in early childhood), academic achievement, and stable employment are also important predictors of disposition—roughly accounting for the remaining 60 to 70 percent of variability.

“If you’re pessimistic and you hear that you probably say, ‘Oh God, I’m doomed,’” Scheier says with a laugh. “If you’re optimistic, you think, ‘Oh, 70 percent variability—that’s not bad!’”

Neither optimists nor pessimists have a lock on reality.

Scheier doesn’t put much stock in depressive realism, the much-publicized idea that depressed people are better at assessing real-life conditions (see p. 19).

Taking the glass-half-full metaphor, he says, “I would be willing to bet a considerable amount of money that if you ask somebody who was very pessimistic and somebody who was very optimistic to point to where the waterline is, they would not make an error. They would know where the waterline is in a glass. And what they’re doing is just interpreting it differently.”

Optimism begets optimism.

Once a Negative Nancy, always a Negative Nancy? Not necessarily, Scheier says.

Though the research is still fairly limited, preliminary studies show that optimism increases slightly over the course of a person’s life. On the other hand, extremely difficult life events, such as cancer diagnoses, appear to take a toll, causing a decline in positive outlook.

Still, barring extreme circumstances, optimists tend to stay that way.

“There does seem to be a relatively stable tendency to view the world in a more optimistic or pessimistic way,” Scheier says. “There’s a high amount of consistency in terms of how people rate themselves across the decades.”

Outlook matters.

“The reason why pessimists and optimists obtain better or worse [life] outcomes, is that they really cope differently with challenges and stress,” Scheier says. Compared with pessimists, optimists adapt better to difficult situations and are less likely to give up in the face of adversity. To put it simply: Optimism protects and pessimism hurts.

Of the two, pessimism seems to be the more potent force, Scheier adds. In fact, some early studies have shown that a negative outlook may be a significant risk factor for certain diseases, chronic inflammation, and even unsuccessful in vitro fertilization.

“Not being pessimistic is, I would say, more important for your health than being optimistic,” Scheier says. “Both make a difference, but if you had to choose one, it’s better not to be pessimistic.”

Which, he adds, could actually be good news for all the Debbie Downers out there. In terms of treatment, he suspects it is easier to interrupt negative thoughts than to generate positive ones.

You don’t need to take the test.

So how optimistic are you, really? In just 10 simple questions, Scheier’s Life Orientation Test purports to provide an answer.

But he doesn’t necessarily recommend it.

“I’m somewhat hesitant about just giving everyone access to this thing,” he says. “A person might not know or think [that they’re a pessimist] until they take the test, and then that really alters the way they think of themselves and what’s possible for them.”

Instead, he looks to ongoing research for new insights into how dispositional variations emerge—and how they can be manipulated.

At this point, Scheier says, it’s widely accepted that dispositional optimism/pessimism “has important consequences for all kinds of different health outcomes.” And studying the coping mechanisms that distinguish optimists from pessimists, he hopes, will lead to better behavioral interventions and psychological treatment.

“We have a lot of evidence-based techniques about cognitive behavior modification and those kinds of things that I think might be very, very useful and successful.”