Since the elections, I’ve been reminded of how little in life makes sense and how little common ground we seem to share these days. As Professor Hany Farid, my guest at a California Live! event last September, put it, “We’re not disagreeing about politics anymore. We’re not disagreeing about philosophy. We’re not disagreeing about ideology. We’re just disagreeing on two plus two.”

Sure seems like that. Makes me envy mathematicians; after all, for all its complexity, math offers a compensatory satisfaction: clarity. In mathematics, as in almost nothing else in life, there is the promise of absolute truth.

Not so in math education, apparently, which is the subject of our story about the so-called “math wars,” a long-running battle between would-be reformers and traditionalists, for lack of a better term, over the best way to address poor performance among students in California and the United States, as well as lagging performance of many low-income students of color. The latest skirmishes have mostly revolved around some high school data science courses substituting for Algebra II in UC, CSU, and other college admission requirements.

As California’s Nathalia Alcantara reports, the acrimonious debate has “played out in social media spats, dueling open letters, opinion columns, and even resulted in a threat of police involvement. But while educators, policymakers, and even tech billionaires duked it out everywhere from the Twittersphere to the California State Senate, teachers, parents, and students have been left wondering what it all means for them.”

Sports is another area where order generally prevails (hard and fast rules, mutually accepted boundary lines, clear winners and losers, etc.), and yet confusion increasingly reigns in intercollegiate athletics as well. This is thanks to a host of recent structural changes, from conference realignments to lucrative NIL (name, image, and likeness) deals, that are remaking college sports in dramatic ways. And, as contributor Ron Kroichick reports, even more drastic changes may be on the horizon.

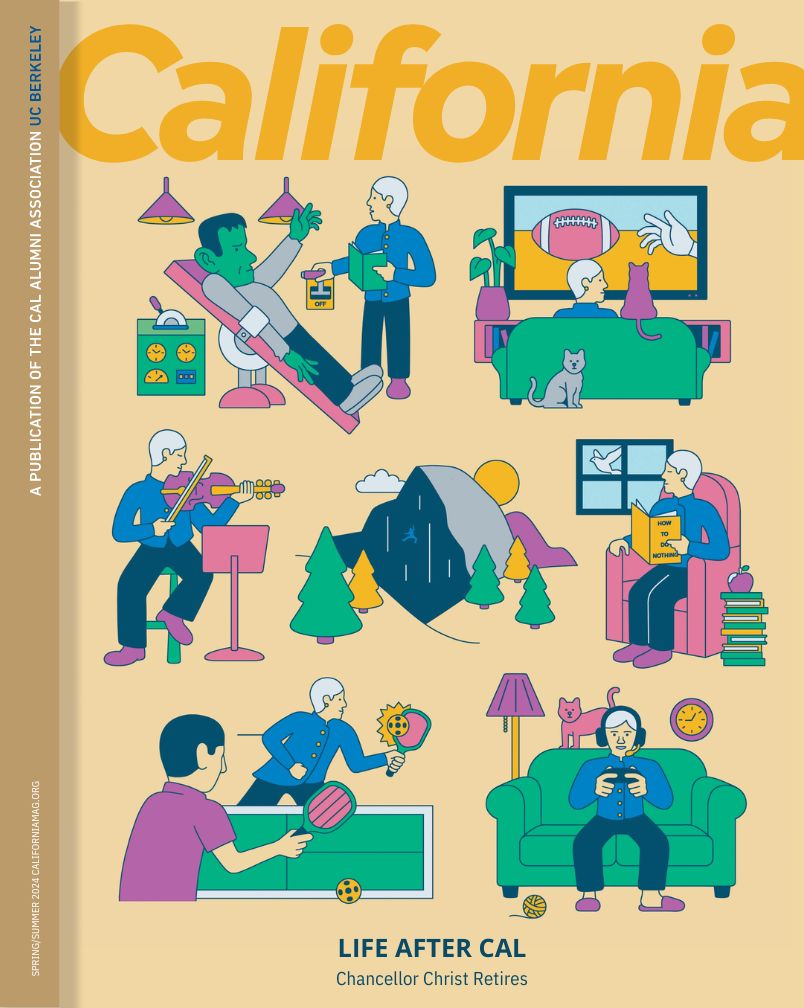

Changes are also afoot in California Hall as Berkeley has a new leader in Chancellor Rich Lyons ’82, who was formerly dean of the Haas School of Business and the university’s first chief innovation and entrepreneurship officer, a role through which he spearheaded the Berkeley Changemaker program. In September, I sat down with Lyons for a wide-ranging conversation covering his views on campus resources, the above-mentioned sports situation, and free speech.

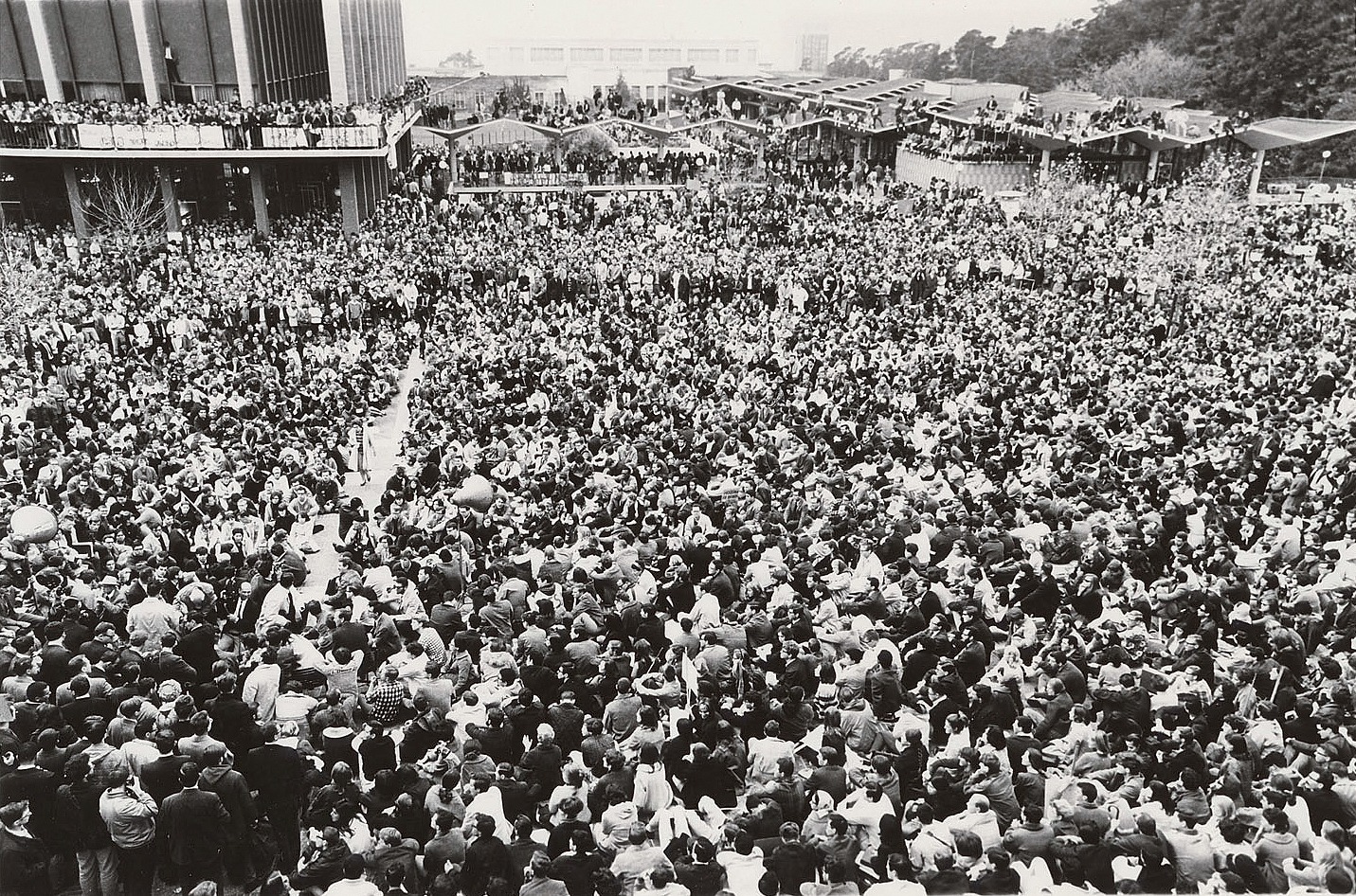

As it happens, this is the 60th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement, which began as a dispute over tabling on the Bancroft Strip and erupted into one of the first full-blown student rebellions of the 1960s. When it happened, this magazine, then called the California Monthly, exhaustively covered events in a special 96-page edition that any editor, including this one, would be proud to take credit for.

Of course, I was not there, having been born a year and a half later. But my friend and former editor of the Monthly, Dick Corten ’65, was. In preparing this issue’s retrospective on that special edition, I emailed him to ask what it was like to experience events firsthand. He wrote: “At first, I didn’t know what to make of it—no scale to measure it by. But it became clear enough that the administrators and the FSM leaders weren’t speaking the same language… Not being on the inside of either camp, I wasn’t aware of the fine details, so I was left with my gut, which didn’t know which way to gurgle. At least not until I stuck around for the impasse of the surrounded police car. I listened to the (shoeless) speechifying from the roof thereof, some eloquent, some pointless. I grew more concerned about possible violence when some in the crowd began shouting at the speakers—not counterarguments, but hostilities.… The shouts coalesced into chants (‘Get off the car!’ and ‘You’re breaking the law!’). They started throwing lit cigarettes and matches into the circle of demonstrators seated around the car, and my gut told me it was time to leave. Whatever the next stage was, I didn’t want to see it or be enveloped by it. I did form a lasting impression, though. The counter-protestors who shouted ‘You’re breaking the law!’ were willing to inflict burns on their opposition. That struck me as violating a higher moral law, while the other students and their allies were staying civil, speaking in turns, even protecting the paint on the car, and, when the time came, willing to be arrested and possibly convicted for their cause.”

Sometimes, even in the messiest of human affairs, clarity emerges after all, not from any theorem or proof, just from a sense of common decency.

—Pat Joseph