Look, there he is, the new chancellor, introducing himself to freshmen on Sproul Plaza. “Hi, I’m Rich. I’m new here myself.”

Well, not exactly true. He’s certainly in a new role, but with the exception of grad school at MIT (Ph.D. in economics), a six-year stint on faculty at Columbia, and two years at Goldman Sachs, Chancellor Rich Lyons ’82 has been at Berkeley since he was an undergrad himself, making him the first leader of the university since Robert Gordon Sproul to call Cal alma mater.

Most of his 31-year career at Berkeley, so far, was as faculty at the Haas School of Business, where he taught a variety of subjects including currency markets and international finance and eventually became dean. It was in that role that he established a set of “defining leadership principles” that have stuck to the business school ever since and helped separate Haas from the Harvards and Whartons and Kelloggs: Question the Status Quo; Students Always; Confidence Without Attitude; and Beyond Yourself.

More recently, under former Chancellor Carol Christ, who retired last June after seven years at the helm, Lyons was appointed the university’s first-ever chief innovation and entrepreneurship officer, where he helped foster a growing ecosystem of Berkeley startup incubators and entrepreneurial initiatives. Every chance he gets, he touts the impressive fact that, per the financial data and research clearinghouse PitchBook, Berkeley boasts more venture-funded startups than any other university.

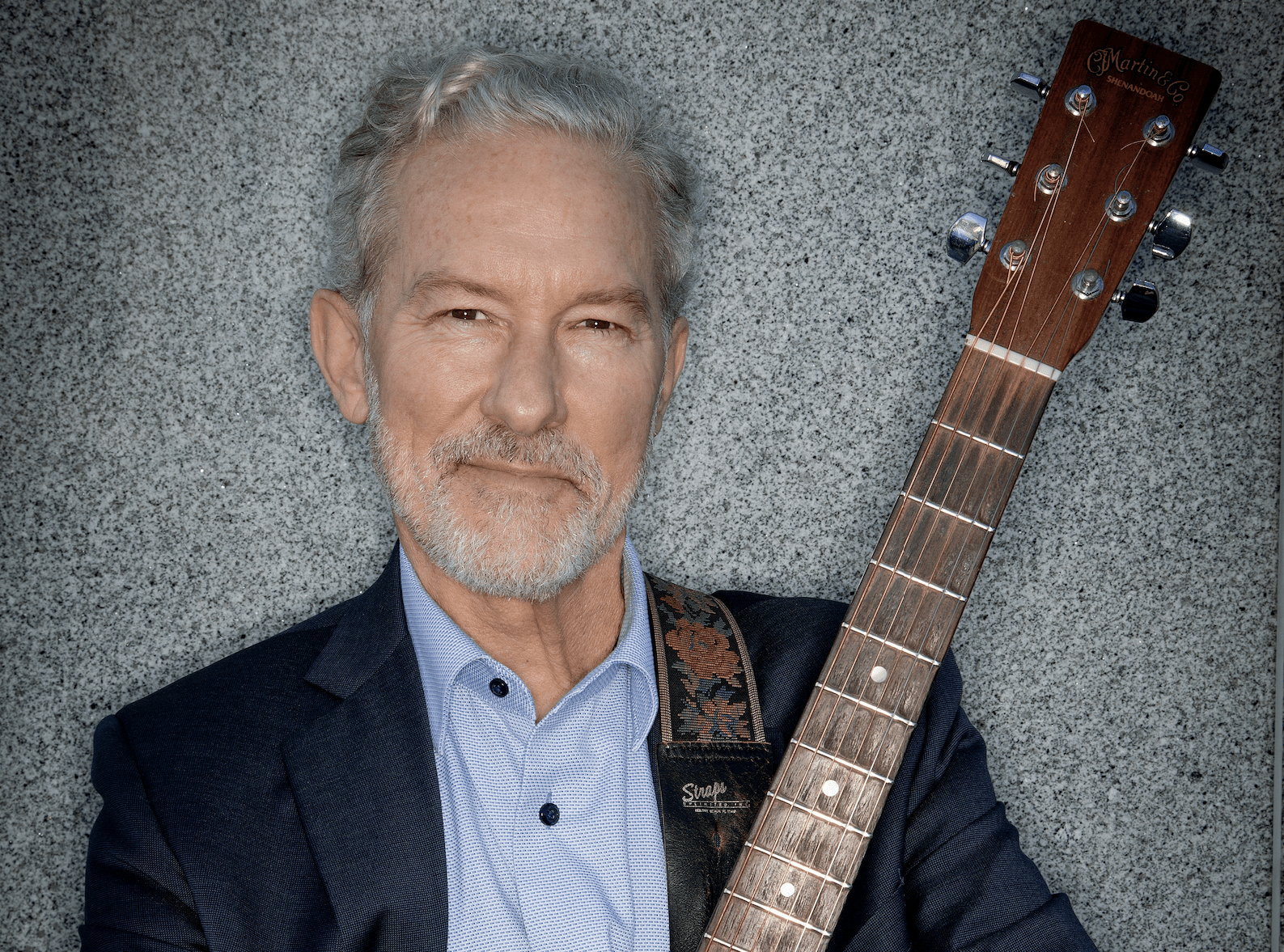

Lyons also, every chance he gets, likes to break out his guitar and sing. Listen: There he is at the 2017 convocation belting out “The ‘Bear’ Necessities,” scattin’ away in his gown like Louis Prima in scholar’s garb. And there he is on YouTube, in street clothes, wearing a foot tambourine, busking in the Berkeley Farmers Market, with all funds going to the Berkeley Free Clinic. The song: the Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil,” which, well, interesting choice, although perhaps not altogether inappropriate for “a man of wealth and taste.”

In August, when he was still getting settled in his new digs in California Hall, I met with Chancellor Lyons for a long-ish sit-down interview. It was my third time talking to him for the magazine. Each time he’s been in a new position on campus. As usual, he wore a blue and gold striped tie, a Cal lapel pin, and a big, broad, damn-glad-to-be-here smile. I joked that the next time I interviewed him I half-expected it would be in the governor’s office.

Not so, he said.

“People ask, ‘What’s your next aspiration? Do you want to be president of this or that university?’ Or, you know, ‘Do you want to be a politician?’ No, I don’t! This is my place. This is the place that transformed my life, and that’s what keeps me locked in.”

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

We want our ideas to have impact, and somebody has to be listening, and I need to do my best to get them to listen. That’s what I’m going to do.

When people hear I’ve interviewed you before, they ask me what you’re like and I usually say, well, he’s a salesman. I don’t know if you like that characterization, but I mean it in the best sense. The other thing I say is that whenever I’ve pushed back on your ideas, you roll with it. You listen to the criticism and don’t take offense.

I do my best to listen. I do. I’m in listening mode now.

You know, the word “salesman” is something a lot of people have a very negative connotation of. But if I asked what is it that a president or chancellor of a university needs to do, I think most people would say, de facto, 80 percent is sales. What are we about? Why do we matter? How do we speak to people more widely in society? How do we build more trust in higher education? How do we get donors to invest in this place? All of that. So, I hope people will not associate sales with something that is not well-aligned with being a great chancellor. But I am concerned, speaking frankly, that some people will.

Well, again, I don’t mean it as a negative. I think of the Daniel Pink book To Sell Is Human. He makes the case that, no matter what you’re doing as a career, you’re selling.

Can I put a slightly different face on it?

You know, I’ve been an academic my whole life. We sell our ideas. That’s what we do. If nobody’s listening to your research, if nobody’s reading your papers, if graduate students don’t want to be your Ph.D. students, you haven’t sold anything. Yet there probably isn’t a single faculty member who would describe him or herself as a salesperson, right? Not a single one. And that’s a really important audience around here. But we want our ideas to have impact, and somebody has to be listening, and I need to do my best to get them to listen. That’s what I’m going to do.

You mentioned being in listening mode yourself. I was wondering if that was necessary, since you have been here for so long, and whether you can’t just hit the ground running.

It’s totally necessary. One hundred percent. I think there are a lot of dimensions in which I can hit the ground running. I do think I have that advantage. I’m also just talking to people about different stuff and it’s like, “Wow, your world is complicated. Your portfolio is complicated.” Even my direct reports. It’s the old drinking-from-a-fire-hose metaphor. So, yes, I know an awful lot, but Berkeley’s this big, beautiful, complicated place, and I too have more to learn about it.

It is a big, beautiful, complicated place. And we’ve talked about this before, the difficulty of corralling it into a single identity, since there’s Cal and Berkeley and California; sports and academics and research and free speech and radical politics… I know that it’s been important to you to define it as carefully and cohesively as you can. Is that still true?

Absolutely true. And I think when we define that, it’s not just a marketing or publicity exercise. It’s like, what values do we stand for? What values do we want to stand for? How are we defined in terms of our mission? How is Berkeley different from other institutions?

I think we have opportunities here. One small example: Do people on the East Coast understand that Cal or California is Berkeley? Many of them actually don’t, right? And we’re now in the Atlantic Coast Conference, and we have an opportunity to get those two concepts wrapped up a bit.

You are the first Berkeley chancellor to also have been an undergrad here. But you grew up in Los Altos, with Stanford practically in your backyard. Why did you come to Cal?

An older brother came here, so it was familiar. And I got to come to football games when I was 12 and 13. That was a big part of it.

My personal values align so much with the things that are so distinctive about Berkeley, like questioning the status quo—this mindset that, you know, there’s got to be a better way to do this. I love that! That’s just not the way I would feel at a lot of institutions.

Take us back. What was it like, your first day as a student on campus?

Ah, good question. Well, you know, I didn’t get into the residence hall. And, like so many undergraduates still today, I was scrambling for housing and trying to find my neighborhood, as Carol [Christ] liked to say.

The place was alive and ideas were colliding, and people disagreed. I took sociology as a freshman and, until then, I didn’t know the field existed. Arlie Hochschild was the professor and it was like, “Well, here’s a new lens on the world.” Absolutely fantastic.

I felt right from the beginning, like, intellectually, this is electric. I took a bunch of courses I wasn’t expecting to take. I took some French and just kept going in it. I took some physics and kept going, neither of which was my minor, but it was like, I just love this stuff. Yeah, so I felt turned on from the beginning.

You said you didn’t have housing. Where’d you end up?

I ended up living in a fraternity. SAE. Sigma Alpha Epsilon.

How was Greek life?

Well, I was a serious student, and in many ways, it reinforced my studiousness, because I was with a bunch of people who were terrific students in engineering and grinding even more than I was. It was super-supportive for me on the academic side of things. And there was a social side, a connected side, that was important. But it’s tough coming in for freshmen. “Find your neighborhood”—that’s easy to say and kind of hard to do.

That’s a criticism one often hears about Cal—just the sheer size of it and the sense of anonymity that students sometimes feel, that they’re lost in this sea of people.

I don’t really buy that narrative. Yes, we know that there’s heightened anxiety and depression. Those are very real things. At the same time, how much of that is a function of the fact that Berkeley is a big place? We really have to be careful about causality.

I think Berkeley, because it is a concept, because there’s a gestalt here, … there’s a set of shared values … that just gets people going here. It certainly got me going. And, you know, when I think about why I’ve been here as a faculty member for more than 30 years, but also going back to when I was an undergrad, it’s because my personal values align so much with the things that are so distinctive about Berkeley, like questioning the status quo—this mindset that, you know, there’s got to be a better way to do this. I love that! That’s just not the way I would feel at a lot of institutions.

Now, that values alignment doesn’t work for every undergraduate, but the world is challenging. It’s hard to find one’s place in the world, and Berkeley is reflective of that world. But I think our distinctiveness actually helps people feel like they’ve got commonality here. I like what this place is about and that’s meaning-making. I know it brought meaning to me.

We’ve been in a state [of] perennial austerity. If you look back when I was an undergrad, two generations ago or so, the state of California provided nearly 50 percent of Berkeley’s operating budget. Now it’s around 12 or 13 percent.

Okay, so, what are the things that you want to accomplish short term, middle term, long term?

Well, part of why I, or any leader, needs to be in listening mode is to help sharpen the early ideas. So I’ll offer a few things, but I would stress that we need to do a strategic planning process. This is an institution that’s committed to faculty governance. Faculty will be very, very involved, no question about that. Some early thoughts, though, are things like, well, resources.

In the personal statement that I submitted as part of the search, I used the phrase “resource leadership.” Can we imagine a Berkeley that we would describe as being in a state of financial thriving? Can you actually come up with something new that might produce that? And, actually, we can. Without going into too much detail here, part of what I’ve been looking at exclusively over the last five years is, quote/unquote, innovation and entrepreneurship. Now, if we ask the question, “How does Berkeley participate more, in a values-consistent way, in the economic value it creates?”—that’s an interesting question. I mean, how historically have we answered that question? One answer is philanthropy: People create value and they give some of it back to us. But what else can we do? Well, you know, we as a university produce more funded startups than any other university in the world, period. And so then the question is, do we have an economic interest in those startups? Again, a values-consistent one. We’re not a hedge fund or a venture capital fund.

But I’ll give you another example. We have received over the last year or so $75 million in gifts that came in, in a restricted way. These gifts have to be invested in a set of affiliated venture capital funds, but when the money comes out the other side, it’s largely unrestricted, and it will have a multiplier. It doesn’t come out in the next year or two years. These venture capital funds pay out in eight to twelve years. But a middling return for one of these funds is what we call 3x. So, if you invest a million, at the end of 10 years, it’s worth $3 million, right? So if these funds go 3x, then $75 million becomes $225 million and that’s unrestricted.

Would that alone transform Berkeley’s financial model? No, it’s not enough. But now if I said, I’ve got 10 of these examples, and they are going to produce 10 incremental, unrestricted, $100 million cash flows, now that’s interesting. That would change the operating budget in a really big way.

This is stuff we weren’t even thinking about five years ago. It’s really fresh. And we’ve got to do it in a values-consistent way, right?

You keep stressing values-consistent. But do you have examples in mind of where you might go awry of your values, or it might be a hard call, because there’s so much money on the table?

Well, if you could imagine a situation where we are taking money away from scholarships and putting it into venture capital funds, something like that, then you’re distorting what we do, which is research, teaching, and service to produce long-term societal benefit.

Okay, so, a donor comes to you tomorrow and says, “Do you want $75 million for scholarships, or do you want it in your VC fund where it could go 3x,” what would you decide?

Well, I think you say we need it in scholarships. I think our immediate needs in the operating budget are just intense right now. We’ve been in a state that is not unreasonably described as perennial austerity. If you look back when I was an undergrad, two generations ago or so, the state of California provided nearly 50 percent of Berkeley’s operating budget. Now it’s around 12 or 13 percent. At the same time, faculty want more investment in deferred maintenance, we need to increase the size of the faculty, we need to increase the amount of housing to guarantee two years. There are just some things that we need to work really hard at.

Alumni engagement is a huge part of how we prosecute our mission, a huge part of how we do research and how we teach and do public service. I mean, it’s really important, right? So it’s not just a nice-to-have. It’s bigger than that.

So, where I left it with Chancellor Christ when I spoke to her for our last issue was the obvious question: What do you think are the big challenges for your successor? One of the big ones was athletics. So if you don’t mind, let’s transition to that. As I understand it, with Cal now in the ACC, expenses are going up considerably and revenue is going down. That’s a big hit for a program that already runs at some deficit. Does this mean we have to trim the roster of sports teams?

Well, I think that one of the things that the UC system did for Berkeley is we got an extra $15 million a year for three years for athletics. And it may be extended beyond three years. Then we have another $10 million a year from UCLA, the so-called Calimony for leaving the Pac-12. So if you look at that $25 million, and then you look at what we’re getting from the ACC—basically a one-third share of $33 million—that’s another $11 million, okay? If you add $11 million to that $25 million, you get to $36 million, and that’s actually right around and slightly above what our Pac-12 media contract was. So, it doesn’t mean we don’t have a lot of analysis to do over the next two or three years, but it does give us some breathing room. And that’s by design, right? I think the regents and the president realized that whoever the next chancellor is, if they’re walking in and there’s nothing there.… But, I mean, here’s a scenario: the ACC dissolves next year. For those close to this, that’s not an impossible thing, right? So it dissolves and there’s a reconstituted conference, where we come in at full economics, so that instead of a third of 33, we come in at $45 million. And we still have the 10 and the 15. These are interesting, not unreasonable scenarios.

But here’s another way to think of this. Athletics is this big category, and it’s complicated, right? Complicated things are usually easier to think about in a disciplined way, and it’s helpful if you break them into sensible parts. So, part one: revenue sports—principally football and men’s basketball. Part two: men’s Olympic sports. Part three: women’s Olympic sports. Those latter two labels aren’t quite right, but you get the picture.

So, those categories span the sports that we’re in, and then the question is, can we make men’s basketball and football self-sustaining? The old modus operandi was that we cross-subsidized from this category to the other categories. Well, that model’s going away in the near term. If we’re quite successful, we could imagine some cross-subsidies coming back down the road, but that ain’t gonna happen in the next one or two or three years.

All right, so men’s Olympics sports: Can we get them to be funded through endowments? We’re working on some very big gifts that will come in, and we’re optimistic that we can actually do it. We’re close on a number of sports, and we’ll have some announcements very soon. [Shortly after this interview, a $23 million endowment gift was announced for men’s and women’s golf.] Ideally, that whole constellation would be endowment-funded. That’s not going to happen in five years, but if you’re looking out 10 years, that’s not a crazy aspiration.

Now, women’s Olympic sports, because most of those programs have less history, there isn’t as much philanthropic capacity behind them. And there, not only because of Title IX but because it’s the right thing to do, I’m going to have to cross-subsidize those out of our central budget for the foreseeable future.

How important is football to American universities, and Cal in particular?

I liked Carol’s metaphor that sports is a front porch, a living room, a way to connect, right? It’s part of the ties that bind for a lot of alumni. If you had to pick one thing that keeps alumni engaged, I think athletics is probably on the top of most people’s lists as a generalized descrip-tion. And if you had to say, “All right, within that category called athletics, which is it? Is it wrestling or is it football?” It’s football, right? It’s the California Memorial Stadium experience for so many people. And if you thought about the counterfactual, if you just sort of said, “Where would Berkeley be if not for the contributions, not just financial, but in terms of time and effort of its alumni?” I mean, alumni engagement is a huge part of how we prosecute our mission, a huge part of how we do research and how we teach and do public service. I mean, it’s really important, right? So it’s not just a nice-to-have. It’s bigger than that.

But then the question is, how are the fundamental elements of athletics going to settle out? You know, it could be that there’s a runaway super league of like 15 teams that own a huge proportion of the economics, and if you’re not in the top 15, you’re still Division I, but you’re in a lower tier. And I don’t know how things are going to play out, but one thing that feels important to me is to at least be at the table when that’s getting sorted. When the music stops, you know, Berkeley wants to have some opportunities. And part of my job is to make sure that football at Cal has opportunities over the next few years.

Are you personally a fan?

Definitely. I graduated in December of 1982, and in late November 1982 was The Play. And everybody says this, but I was in the stadium and I saw that play. And we went to every home game when I was an undergrad. So, yes, I’m a fan.

And the point of my question is just to establish that it’s a priority for you.

Yes, it is. I also want to say, though, that I have a different job now. My job is to steward this university. Berkeley is one of society’s most valuable assets. I’ve said that before. I’ll keep saying it. And for the segment of decisions that I have to make, it’s not about whether I’m a football fan. I have to take the long view on the whole of Berkeley.

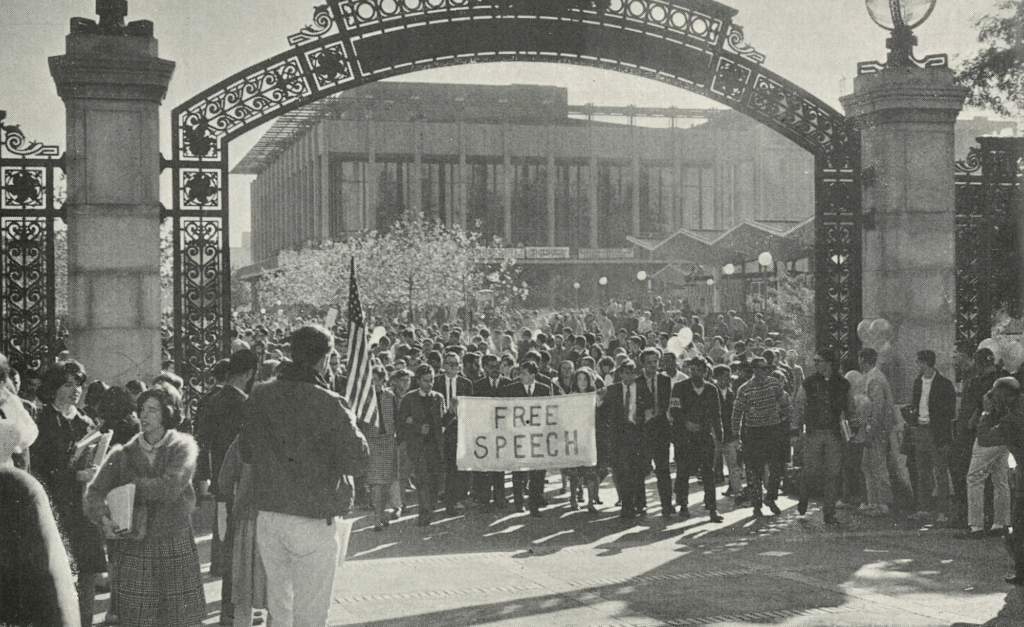

This year is the 60th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement. Obviously, free speech is a perennial issue everywhere, and never more so than at this particular junction with Israel and Gaza and the elections. And I think we can pretty much expect more tensions along those lines. The FSM was fundamentally about the ability to exercise political speech. It was also largely anti-administration. How does a Berkeley administration today celebrate the FSM without co-opting something that was antithetical to it?

I think by recognizing that that’s exactly what it was.

In 1964, students were told by the university administration that, even out at Telegraph and Bancroft, they couldn’t set up tables and talk to people out there. That was a very limiting context. In reaction, all of the student clubs across the political spectrum banded together. It really was students versus the university. And I think, today, the university leadership is very comfortable sort of saying, “Yeah, we got that wrong.” And we will get other things wrong.

One of the things I’ll share with you is that I’m moving Berkeley in the direction of institutional neutrality. That’s not a zero-one statement—I said in the direction of. But part of why I mention that is, if somebody says, “Berkeley really wants to be on the right side of history on this issue,” well, that’s not really our job. Yeah, we want to make sure that ideas are coming together and have the compassion to understand that when it’s really assaulting somebody’s identity that that’s a big deal. But at the end of the day, if somebody says, “You should really allow this or that to happen because it’s probably on the right side of history,” that does not sound like institutional neutrality to me. And that doesn’t seem like the right lens for making the call on something that is criminal or patently against our few rules that limit freedom of expression.

Here’s one thing that I’m going to do my very best to do: I’m going to do my very best to be consistent, and to be content-neutral.

When you talk about institutional neutrality, are you leaning toward the University of Chicago and the Kalven Report [which insisted on institutional neutrality on political and social issues]? Is that where you would like to arrive?

No, no, that’s zero-one, that’s unequivocal. You know, the chancellor at UC Irvine has put out a statement on statements. I’m not sure that we will do that, but to oversimplify, it says [they’re] not going to put out statements unless certain, quite-stringent conditions are met, unless it is just so odious.

I had to salute Carol Christ for her restraint regarding protest and encampments last spring. Until the occupation of Anna Head [Alumnae Hall], there were no arrests. And, unlike campuses across the country, Berkeley mostly stayed out of the news. But my question is, how restrained can you be, and where do you draw the line?

Great question. It’s a perennial question. I think part of the answer is there are so many dimensions and questions to consider. Is it an incident involving a student or an unaffiliated person? Is this a person or group that has repeatedly engaged in this activity? Is it just very clearly designed to intimidate and harass, or is it peaceful? If it’s designed to harass, there are civil rights protections under Title IX that bar that. So when people say, “Where do you draw the line?” We literally need to draw the line in different places depending upon the circumstances. And I promise you, we will use our considered judgment to do that.

Here’s one thing that I’m going to do my very best to do: I’m going to do my very best to be consistent, and to be content-neutral.

After interviewing Carol Christ last spring, I walked out of California Hall, and Sather Gate was partially blocked by pro-Palestinian protesters, and there was a banner on the ground that you had to step across, or on, unless you wanted to be corralled through the one narrow passage. And I thought, how do you referee this one? You know, they’re not blocking the entire entrance. Have they infringed on my rights? I didn’t feel unsafe, but then maybe I would have if I was wearing a yarmulke or a Star of David… I just remember thinking, “I’m glad I don’t have to referee this.”

Well, one of the things that Carol and her team did very well was engagement.… I like being principles-based. If you ask me, what are you going to do? It’s sort of like, let me tell you my principles, and I’m going to do my best to live by them.

Number one, and these are in no particular order, is engagement. Are you informing them that they’re breaking the rules? Are you informing them of what the consequences might be? I mean, that’s the simplest level of engagement in these tiered responses. So that’s a big one.

Second, transparency. I’m going to try and be as transparent as I can. I’m an economist. We have a lot of economic situations where being transparent is not optimal, right? We love to write down models like that, but the reality is, I’m going to lean toward transparency.

And then the last one is that we have to protect the needs and rights of our whole community. It’s really important. We have 45,000 students. We have staff and faculty and so much more.

So, I’m going to do my very best to be consistent and content-neutral, but also call things out. If you are standing in front of Sather Gate, and you are spreading your message, that is perfectly consistent with our rules. If you are standing at Sather Gate with other people, and you are completely blocking it, to take an extreme example, you have now entered into civil disobedience, and that will be handled differently. And it’s our job to help students understand what the category definitions are, what the consequences are.

Any chance that you’ll be called to testify before the House Committee on Education?

Anybody’s guess. We aim to do the right thing at every instance, and hopefully that will reduce the odds of that happening, but…

To wrap up, tell me what the guitar and what music mean to you.

Thank you for asking. It’s my meditation. It keeps me sane. It’s how I decompress. I play every day. I just have so much fun playing the same songs over again and hopefully getting a little bit better. And it’s something that came later in life for me. I was in graduate school, working very hard in a Ph.D. program, and my life had become really unbalanced. I needed something to create some balance, and so that’s where I went. I started playing guitar. And I haven’t looked back.

Well, I think my favorite song that you play is the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.” But I have to ask, how long have you been in cahoots with Satan?

[Laughs] You’re overreading!

I’m just preparing you for Congress.

[Laughing] Oh, my gosh, yeah.