Mario Savio’s design for a Free Speech Movement monument

Berkeley students today take for granted that the Free Speech Movement (FSM) was a major event whose memory the University commemorates. They can get a snack at the Free Speech Movement Café (opened in 2000) while viewing photos, leaflets, and other artifacts of the Berkeley rebellion. They can sit on Sproul Hall’s Savio steps, named for FSM leader Mario Savio in 1997, the year after his death. Every fall they can attend the lecture series that bears his name and see the Mario Savio Young Activist Award given to an idealistic student.

But this honoring of the FSM is relatively recent. Much of the California electorate in 1964 were outraged by the disruptive protests, which broke campus regulations and were portrayed as subversive and anarchical. When those tactics spread to campuses across the nation, a backlash against Berkeley-style protests grew, enabling such conservative politicians as Ronald Reagan to gain office by pledging “to clean up the mess” in Berkeley.

Even as late as 1990 Berkeley’s administration was reluctant to honor the movement. Back then a group of FSM veterans and faculty, dubbing themselves the Berkeley Art Project, held a design competition for a work of art honoring the FSM to be housed on campus. Berkeley Chancellor I. Michael Heyman, afraid of the monument’s polarizing potential, ruled on July 29, 1990, that the only acceptable monument would pay tribute to the idea of free speech without “reference to a particular ideology or movement.” So it could not name the FSM—ironic for a piecce honoring a movement that championed free expression. The chosen work of art, Column of Earth and Air by Mark A. Brest van Kempen, makes no mention of the FSM.

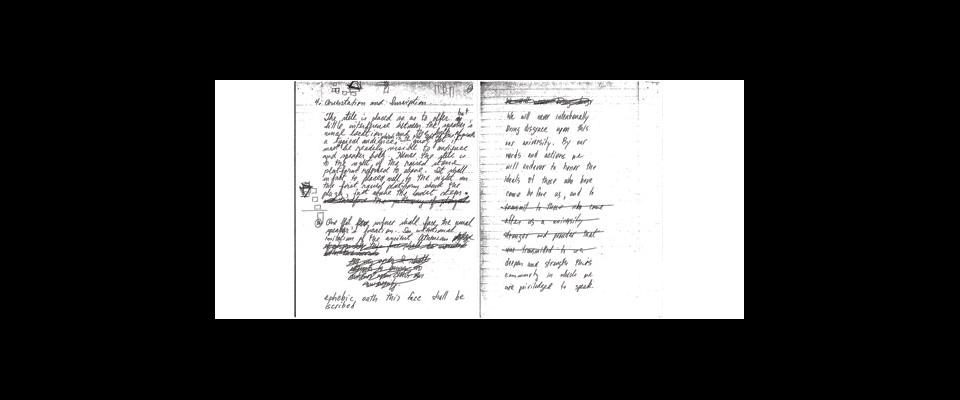

It was not until Mario Savio’s death in 1996 that the tide began to turn, and FSM veterans and students succeeded in moving the UC administration to honor the movement. Savio did not live to see these memorials, but it seems likely that he would have been struck by the irony of having a part of Sproul named after him for the same dissident acts that led to his incarceration and suspension from UC in 1964. His private papers (below), which I read as I researched his biography, reveal that Savio had sketched a design for an FSM campus monument. Though never submitted to the Berkeley Art Project, the design reveals much about his views of the movement and the University.

Savio’s design, consistent with his hyperdemocratic politics, included no mention of his or any other leader’s role in the FSM. Though Savio made a number of famous speeches during the Berkeley rebellion (some of which are still quoted in historical studies and films, history textbooks, and even popular culture), his monument carried none of those. Instead he drew on the wisdom of Ancient Greece as well as Berkeley’s own faculty to celebrate the free speech principles and youthful idealism.

The most symbolically radical part of Savio’s design concerned the “free speech area” at Bancroft Way and Telegraph Avenue, closed down by the administration in September 1964. His design took aim at a key symbol of UC’s authority: the brass plates embedded in the entranceway, reading “Property of the Board of Regents: Permission to Pass Revocable at any Time.” He wanted the most central of them removed “with appropriate ceremony” and replaced with a larger, blank plaque, symbolizing the removal of the regents’ power to restrict political expression. He regarded the ending of those restrictions, plus the regents’ pledge to adhere to the First and Fourteenth Amendments, as key FSM achievements. For Savio, the blank plaque also symbolized “the oft proclaimed neutrality of the University with regard to political and social forces beyond the campus.”

A succession of smaller plaques the size of the originals would form a “gently and harmoniously curved” pathway, attesting that Berkeley had become a secure site for freedom of speech. This pathway would culminate just to the right of the Sproul steps, “from which the speakers typically address the community.” Here he placed the main monument, a triangular stele “in honor of and as a token of perpetual commitment to the principles and spirit of the Free Speech Movement.”

Some of the words Savio chose for this monument may surprise those who believe that he was hostile to the University. The late Clark Kerr, then–UC President and nemesis of the movement, thought Savio led the Berkeley revolt because he loathed the University. Kerr made this point in his 2003 memoir, and supported it by citing Savio’s most famous FSM speech. He did use the word “odious,” but not as Kerr suggested. Savio argued that the lack of free speech was odious, and the University ought not to operate repressively. In his idealistic view, Berkeley had the potential to become the locus of constructive thought and action to solve major social problems.

Savio’s reverence for that ideal is most explicit in the text he chose for the side of the stele facing campus orators, as a reminder of their “special responsibility” to use their freedom of speech wisely. The words were in “intentional imitation of the ancient Athenian ephebic oath: We will never intentionally bring disgrace upon this our university. By our words and actions we will endeavor to honor those who came before us, and deepen and strengthen this community in which we are privileged to speak.”

Ancient Greece was the seedbed for much of the monument’s wording, reflecting Savio’s thorough grounding in the classics and his consciousness of the roots of democratic thought. As Savio explained, “Every worthy student movement seeks to restore a society to the best in its root values. In this sense student movements are inherently ‘radical.’ Young people are natural idealists and will desire to implement those values which are deepest and most universal. For us in the West, Athenian democracy, for all its blemishes, has always served to embody those values which we imagine are universal.”

For Savio, the most powerful and poetic words on free speech came from Diogenes. On the surface of the monument facing the audience, Savio placed this Diogenes quotation: “The most beautiful thing in the world is the freedom of speech.” To underscore their universalism, Savio wanted the words inscribed not just in the original Greek and in English but also in Swahili, Spanish, Russian, and Chinese, “a selection of the world’s ‘principal’ languages.”

Savio hoped the words would inspire audiences to be thoughtful and analytical, to judge whether campus orators were exploring important truths or spouting “merely cant.” An additional reason to include Diogenes is that he was a follower of the half-Thracian Antisthenes, who established Athens’s only school open to those not wholly of Athenian descent. “This may,” Savio explained, “be taken to remind us that the renewal of the university” in the 1960s “came about by student involvement with persons who were then largely outsiders to academe, the black Americans”—whose civil rights crusade ignited student activism at Berkeley and nationally.

The only words not from Ancient Greece designated for the monument came from Berkeley’s faculty. Facing campusward, he wanted the Academic Senate Resolutions of December 8, 1964: “That the time, place, and manner of conducting political activity on campus should be subject to reasonable regulation, to prevent interference with the normal functions of the university. That the content of speech or advocacy should not be regulated by the university.”

The resolutions settled the free speech dispute and affirmed the FSM’s position on free political advocacy. But more than reminding students of an old victory, Savio hoped the inscription would serve “as a reminder of high responsibility. All members of the community, whether or not they choose to participate directly in the special life of public discussion, have a special responsibility to protect that life.”