DayGlo

It will come as no shock that daylight fluorescent paint and the black light poster, those iconic emblems of the psychedelic ’60s, trace their origin to Berkeley. No, the surprise is not where, but when.

The story goes that in the early 1930s, Robert Switzer, a Berkeley local and pre-med student at Cal, sustained a serious head injury while working at a tomato quality-control lab. On doctor’s orders, he was confined to a dark room for months. His younger brother Joseph, a student at Berkeley High School, had dual interests in magic and chemistry (the latter as a means to create illusions). Together the brothers developed a fluorescent pigment that glowed under a blacklight, allowing Robert to see it in his dark confines.

Recognizing the magical potential of the invention, Joseph debuted the paint during an act at a local magic convention. His “young, comely” female assistant danced for the crowd and appeared to remove her head, an illusion achieved using what Joseph called “northern lights paint.” His fellow magicians were wowed. The brothers quickly took their product to market. Before long, it was being used by the military for glow-in-the-dark maps and charts, by morticians for specialized embalming fluid, and by police for a crime detection powder (cash dusted with green blacklight powder made bank robbers’ hands glow, at least theoretically).

And, yes, decades later black light posters would adorn the walls of teenage bedrooms everywhere, creating an undeniably groovy vibe.

Soon after, the Switzer brothers invented a product that would be even more widely used: day-glow paint (no black light required). Their fluorescent pigment would be used in product advertising and packaging, safety markings on road signs and airplanes, and, as a 1947 Oakland Tribune article promised, newfangled bathing suits in scintillating colors that “are going to startle you.”

The Switzers’ company, DayGlo, would eventually become a multimillion-dollar operation.

Salad Kits

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who enjoy assembling a salad from scratch, and the rest of us. Rinse, spin, chop, slice, toss, dress… so many verbs, so little time.

Enter agriculture scientist Jim Lugg ’56, aka “the founder of the modern salad.”

Lugg had a hunch that Americans would eat more greens if the salad building were done for them. The problem with ready-made salad was that chopped greens wilt quickly in a plastic bag. As the president of TransFresh, a produce packaging corporation, Lugg was in the business of solving transport problems for fruits and veggies. He knew that warehouses used a carefully controlled mix of oxygen and carbon dioxide to preserve produce. What if the same principle could be used to keep romaine crisp in a bag or box?

In 1989, thanks to Lugg and his team of fellow researchers, the first-ever salad-in-a-bag hit grocery store shelves, the Fresh Express Family Classic Garden Salad Blend; in the time it takes to read the name you could be eating it already. Today you can choose from a wide selection of fancy-sounding, preassembled bagged salads such as gorgonzola pear, green goddess, Mediterranean crunch, maple bourbon bacon, and more.

Farm to gas-injected plastic bag to table.

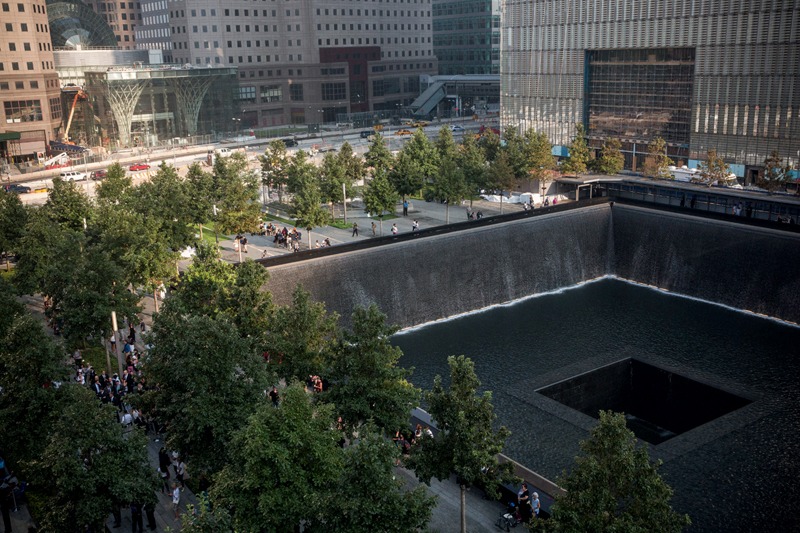

9/11 Memorial

In 2003, renowned landscape architect Peter Walker ’55 received an unexpected phone call from Michael Arad, a young, New York City–based architect. Arad had just learned that he was one of eight finalists for the 9/11 memorial planned for the site of the collapsed World Trade Center towers in Lower Manhattan. While most of the other seven finalists consisted of architecture teams, Arad was a solo act, a relatively inexperienced NYC Housing Authority employee earning $50K a year designing public buildings. He asked Walker, an expert in the design of public open spaces, to join him in his presentations to the memorial jury panel. Walker would lend gravitas and an air of feasibility to Arad’s proposal. Walker agreed, and Arad’s design won.

Ten years to the day after the towers fell, the 9/11 Memorial, based on Arad and Walker’s joint design, was unveiled. Its focal points are twin acre-sized recesses in the footprints of the former towers. In each, water cascades down the four walls, descending 30 feet to a reflecting pool, then plunges again into a smaller square recess at the center of the pool and, finally, out of sight. Bronze panels surrounding each pool list the names of those who died in the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Walker’s task was to design the open space surrounding the two pools.

“Our job was to somehow make a park … that could work as a memorial and could also work as a public open space, where one function didn’t counter the other function,” Walker later said.

Today, thanks to Walker’s vision, the pools are surrounded by more than 400 swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor) trees. Nestled among the oaks is a single pear tree known as the “survivor tree.” It was discovered barely alive beneath the wreckage of the towers, nursed back to health, and replanted on the memorial site as a symbol of resilience.

Fuzzy Logic

When Cal Professor Lotfi Zadeh published his now-famous paper entitled “Fuzzy Sets” in 1965, it was met with disdain by many.

Classical mathematical logic is based on separating statements into the categories of true or false, represented by 1 and 0. By contrast, Zadeh’s fuzzy sets included an infinite number of gradients between 0 and 1, which he felt might better capture the nuances of real-world phenomena. In a sense, Zadeh was taking the black and white world of mathematical logic and turning it gray. Feathers were ruffled.

Fuzzy logic is “the cocaine of science,” declared computer scientist and fellow Berkeley Professor William Kahan, who did not mean it as a compliment.

Others were all too ready to snort Zadeh’s line of thinking.

While traditional logic was good at dealing with straightforward problems, fuzzy logic suggested the possibility of tackling more complex, ambiguous challenges. Artificial intelligence experts, in particular, were intrigued that fuzzy logic might more closely mimic human decision-making.

Real-world applications of fuzzy logic came in the ’80s and ’90s with the advent of smarter electronic control systems. Suddenly just about everything was getting fuzzified: subway trains to car transmissions, cameras to microwaves. Today most appliances have had a fuzzy upgrade. While a

“dumb” washing machine fills the water to the level set on the dial, a fuzzy washing machine considers an array of factors, like the weight of the clothing, fabric type, and how dirty it is, and adjusts its settings accordingly.

It should be noted that Professor Zadeh was beloved by his students who found him caring and approachable. Warm and fuzzy.

No-Fault Divorce

1969 may have been a summer of peace, love, and rock ’n’ roll, but for Californians at least, it was also the summer of divorce. On September 4, then- Governor (and divorcé) Ronald Reagan signed the Family Law Act of 1969, the nation’s first no-fault divorce bill, allowing couples to dissolve their marriages without either spouse having to prove wrongdoing by the other. The law was coauthored by Cal law professor and family law expert Herma Hill Kay.

Before no-fault divorce, a husband or wife had to convince a court that their spouse had destroyed the marriage through bad behavior, like cruelty, cheating, or neglect. This often meant acrimonious court proceedings and much airing of dirty laundry, something no-fault advocates like Kay said could be psychologically damaging for the couple’s children. And in cases where husband and wife were equally sick of each other but neither had committed divorce-level misdeeds, they’d often invent marital transgressions to meet the legal requirements. In other words, they’d commit perjury.

“We could do away with much of the legal harshness of divorce,” Kay once said. “Perhaps the law’s machinery can use a different device for divorce than for criminal offenders.”

By the end of the 1970s, most states had followed California’s lead and passed no-fault divorce laws (New York was the last to do it in 2010). This new legal escape hatch was a boon to unhappy spouses everywhere and a lifeline for women. A 2006 study revealed that following the adoption of no-fault divorce laws, states saw decreases in both female suicide and domestic violence.

The laws did stand to hurt one demographic, however: divorce lawyers. A streamlined legal process meant far fewer billable hours per case. Lucky for them, the ’70s and ’80s would provide increased volume to make up for it.