People still have issues with the Sixties. It was a decade of idealism and divisiveness. Three years into the decade, Bob Dylan railed against mothers and fathers throughout the land. Don’t criticize what you can’t understand. Jim Morrison proclaimed we want the world, and we want it … now. Much of this can be explained by demographics and the arrogance of youth. Then there were the drugs, especially the psychedelic drugs.

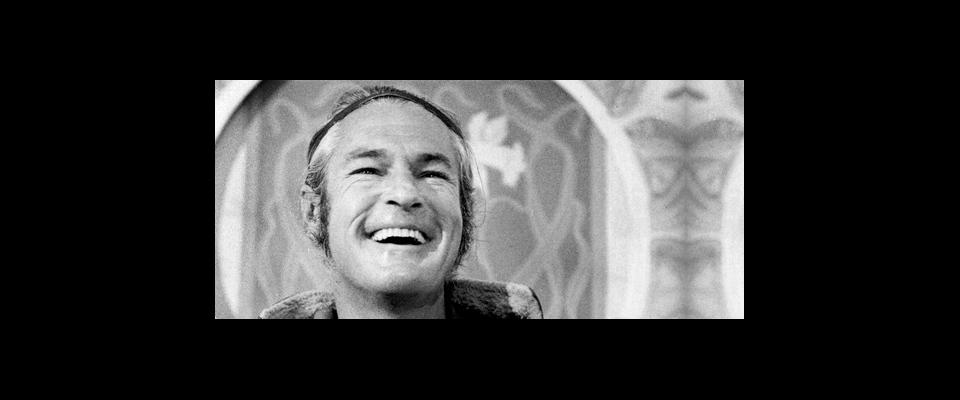

In the summer of 1960, a clinical psychologist at Harvard University named Timothy Leary, who had sampled some magic mushrooms during his summer vacation in Mexico, became convinced that psychedelic drugs would revolutionize psychology and change the world. He started a research project that soon morphed into a campus drug cult. In 1963, the same year Dylan released “The Times They Are A-Changin’,” Leary was kicked out of Harvard and was thrust into the national spotlight. He crowned himself “high priest” of the psychedelic counter-culture and emerged as one of the most polarizing figures of that divisive decade. Richard Nixon called him “the most dangerous man in America.”

It has now been 50 years since Leary took those magic mushrooms, and 14 years since he died, but people still have issues with Timothy Leary. To set them off just utter three letters—L, S, D—and they remember him, mostly for the backlash he inspired. Timothy Leary was very much on the mind of America when President Nixon declared what has become the nation’s longest and least successful war—the War on Drugs. People forget that LSD was completely legal until 1966. In the 1950s, it was seen by many clinical psychologists as a promising new tool to help us understand the human mind. Hundreds of research papers were written about the drug. There were indications that it could be used as a treatment for alcoholism, depression, and other psychological maladies.

LSD worked in a different way than other drugs. It gave some people instant insight and new understanding into habitual and harmful ways of thinking and behaving. There were other studies showing that LSD and other psychedelics could help healthy people live happier lives, foster creativity, inspire wonder, awe, and empathy. They could give us a taste of transcendence.

But Nixon’s War on Drugs was not just a battle against street drugs. It put a halt to serious scientific research into the beneficial uses of psychedelics, which were classified as “Schedule One” drugs, meaning those considered easy to abuse and with no legitimate medical use. Scientists and other members of the academy learned that a quick way to ruin your university career was to propose a research project involving psychedelic drugs—especially LSD.

Four decades later, there are now more university-sponsored and government-approved research projects involving psychedelics than at any time in the last 40 years. Researchers at UCLA, Johns Hopkins, and New York University are involved in separate studies using psilocybin—the active ingredient in magic mushrooms—to treat anxiety in cancer patients. A South Carolina psychiatrist has gotten approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a pilot study using MDMA, a psychedelic drug also known as “ecstasy,” to treat U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). A researcher affiliated with Harvard University (the same school that ousted Timothy Leary) is studying reports from illicit users that claim LSD can be used to successfully treat cluster headaches.

Other psychedelic drug research is more basic—simply trying to understand how these mysterious compounds work in the human brain. MDMA, for example, produces feelings of empathy and trust in many of its users. That’s why some therapists have begun using it to treat rape victims and shell-shocked soldiers. But exactly how does the drug produce these feelings? Researchers are fairly sure the answer has something to do with the drug’s effect on serotonin, a chemical in our bodies that acts as a neurotransmitter sparking various emotional states.

Leading this research is a team that includes a young psychedelic drug researcher with the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute at Berkeley. Matthew Baggott, Ph.D. ’10, spent seven years studying drug toxicity and the mechanisms of the psychedelic state. Baggott did his MDMA research under Dr. John Mendelson, a senior scientist at the Addiction and Pharmacology Research Laboratory at the California Pacific Medical Research Center in San Francisco.

Baggott and Mendelson were among dozens of drug researchers who presented their latest findings at an international conference on “Psychedelic Science in the 21st Century.” For three days in April, hundreds of researchers, therapists, unrepentant hippies, and other connoisseurs of the altered state took over a Holiday Inn near the San Jose International Airport. On the main stage, coats and ties outnumbered tie-dyed T-shirts. But those in search of a ’60s flashback merely had to wander over to the exhibition area, where a kaleidoscopic display of psychedelic paintings and “visionary art clothing” sent minds swirling back to another era. A packed house, changing attitudes in the federal government, and a sudden wave of positive media coverage from The New York Times to Scientific American gave the proceedings a triumphant air.

“This field of research is finally coming of age,” said David Nichols, a veteran researcher who teaches at the Purdue University College of Pharmacy and at the Indiana University School of Medicine. “As Crosby, Stills and Nash said, it’s been a long time coming.”

In his presentation, Baggott explained how his team advertises on Craigslist to find healthy volunteers willing to take ecstasy in Dr. Mendelson’s San Francisco lab. “This research is funded by the National Institutes of Health,” Baggott noted, “so if you are a U.S. citizen, these are your tax dollars at work.”

That line nearly sparked a standing ovation.

Baggott paused, then continued his talk.

“We are not trying to develop new medications. We are trying to understand how these drugs affect people, which is still quite mysterious. We’re trying to develop a common language to understand the drug experience, enabling us to reduce the risks and reap the benefits of these drugs.”

Baggott conducted placebo-controlled, double-blind experiments—meaning neither the researchers nor the subjects knew if they were getting MDMA or a placebo. Subjects who felt inebriated were asked to quantify the effects, such as the extent to which they felt a “closeness to others” when they were high.

It’s slippery science. Baggott and his team were trying to measure ineffable emotional states like empathy and trust.

Baggott and Mendelson’s subjects also were shown drawings of facial expressions that reflect basic human emotions such as happiness, sadness, fear, and surprise. They’ve found that ecstasy seems to diminish a subject’s ability to recognize fear. That could be one reason ecstasy users report greater feelings of trust and compassion while they are on the drug.

“We didn’t expect to find that,” Mendelson said. “We thought they’d show some improvement in seeing happy faces. But it is understandable that MDMA is not doing something beneficial, but impairing some other process. Most drugs, in general, work by screwing something up. People don’t think about this too much. Antibiotics work because they screw up the ability of bacteria to make cell walls. Cancer drugs work because they interfere with the ability of cancer cells to copy DNA. So it’s logical that MDMA would work the same way.”

Mendelson said this inability to recognize fear could explain why so many young people use MDMA at all-night dance parties fueled by the drug. “It allows them to overcome their reluctance to meet new people,” he said. “What is a rave? It’s a setting with a bunch of strangers. It’s weird. It’s loud. MDMA makes them less fearful, less uncomfortable in that situation.”

While that may feel good, Mendelson said, it’s not necessarily a good thing. “Fear-based learning is important and very useful,” he said. “One thing that organisms desperately need to figure out is how not to get killed. If you are a bug and you see the shadow of a bird, you can’t spend a lot of time relearning that. You have to learn it the first time because there may not be a second time.”

MDMA does not produce the visual distortions of classic psychedelics like LSD, nor are users as likely to have an overpowering and psychologically harrowing “bad trip.” But the drug can be dangerous when abused. There have been numerous reports of MDMA overdoses, some of them fatal—including a June incident at the Cow Palace, when 16,000 celebrants packed that Daly City arena for an event called “Pop 2010: The Dream.” Two men, ages 23 and 25, died of an apparent overdose of ecstasy, and seven others were hospitalized.

One of the goals of Baggott and Mendelson’s research is to understand whether these deaths can be attributed to MDMA toxicity or to secondary causes, such as dehydration and overheating after hours of non-stop dancing.

Most of the researchers at the Psychedelic Science in the 21st Century conference were less interested in studying the dangers associated with these drugs. They’re eagerly picking up on research that began in the early 1960s into how these substances can be used as adjuncts to psychotherapy.

In one study led by researcher Michael Mithoefer, a South Carolina psychiatrist, 21 patients suffering from PTSD participated in three therapy sessions. Half the participants had been given MDMA, and the other half a placebo. Most of these patients were women survivors of sexual assault or childhood sexual abuse. The sessions were held three to five weeks apart, along with weekly talk therapy visits designed to help them prepare for whatever insights the drug might reveal and to discuss any drug-fueled revelations. Researchers hoped to show that MDMA’s ability to enhance trust, empathy, and openness would make it easier for patients to recount a traumatic event and examine their long histories of flashbacks, anxiety, panic attacks, or other damaging psychological after-effects from sexual abuse. A two-month follow-up study revealed that 80 percent of the patients who took MDMA no longer had sufficient symptoms to be diagnosed with PTSD, compared to 25 percent of those who took a placebo. According to the researchers, patients with MDMA-assisted therapy also did better than those treated with traditional prescription drugs, such as Zoloft or Paxil.

Other researchers are trying to understand how psychedelics can be used by healthy individuals to inspire greater creativity and foster a sense of spiritual well-being. Roland Griffiths, a professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, administered one to three doses of psilocybin to 36 “hallucinogenic-naïve adults reporting regular participation in religious/spiritual activities.” In a follow-up study 14 months later, published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, 67 percent of them called the trip “among the five most personally meaningful and among the five most spiritually significant experiences of their lives.”

Conference organizer Rick Doblin, who has led a decades-long campaign to restore respectability to psychedelics, is encouraged by these pilot studies. But he warned the assembled enthusiasts at the conference not to too get carried away with their crusade to promote the use of LSD, Ecstasy and other mind-altering substances.

“We have to learn the lessons of the ’60s,” Doblin said. “We must remember what split this society apart. There is no hope in the ‘counter-culture.’ We have to get over this idea that we can have an independent counter-cultural existence that is somehow superior to mainstream culture.”

Doblin, the executive director of the Santa Cruz–based Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, said the new wave of university researchers can learn much from Leary and his research partner at Harvard, Richard Alpert. Alpert was an assistant psychology professor who in the late ’60s traveled to India, returned as Ram Dass, and became one of the leading spiritual teachers of the Baby Boom generation. “Leary and Alpert abandoned science before science abandoned them,” Doblin said in an interview. “They started using pseudoscience for propaganda purposes. We have to become experts on the risks and the benefits and report them both in an accurate way.”

Still, academia hasn’t wholeheartedly embraced research into psychedelics.

In 2007, Berkeley and UC San Francisco became the first American universities since the 1960s to get permission from the FDA for a small-scale research project that administered LSD to human subjects. That research, measuring how LSD might foster creativity in users by measuring the neural activity that accompanies altered states of consciousness, was proposed by Matthew Baggott, this time under the supervision of Dr. Reese Jones, a professor of psychiatry at UCSF. It was funded by the Oxford, England–based Beckley Foundation, a charitable trust that promotes research into human consciousness and was one of the co-sponsors of the psychedelic sciences conference last spring. Beckley Foundation director Amanda Feilding said she was “very, very surprised” when the FDA issued an “Investigational New Drug” (IND) authorization for their proposed LSD study.

Other researchers agreed that getting federal approval for an LSD study was a milestone in the new wave of psychedelic research.

They also point out that the project never really got off the ground. “They only dosed two people and never finished the study,” Doblin said. “Now Matt Baggott has graduated, and they’ve run out of money.”

Baggott and Jones declined to comment on the LSD study, but Feilding acknowledged that little actual research has been conducted. “Matt got diverted into other studies,” Feilding said. “It is not progressing as much as I’d like.”

So far, the federal government has issued IND authorizations for only two studies that administer LSD to human subjects—the Baggott/Jones project and a Swiss study funded by Doblin’s organization.

Researchers in both Switzerland and San Francisco had difficulties finding eligible candidates. And the Bay Area study has apparently been bogged down by disagreements between the funders and the researchers over how to proceed.

It seems people still have issues with LSD.