Here’s the thing about The Thing: It is almost impossible to define. It’s a periodical, but unlike any magazine you’ve seen before. It’s a piece of art, but it’s nothing you’re going to hang on your wall. It’s a functional object, but possibly one you’ll be reluctant to ever use. Subscribe to The Thing Quarterly, and you’ll receive a plain brown-paper package four times a year, the contents of which will be a mystery until you open it. Perhaps it will be a pair of glasses designed by author Jonathan Lethem, or pillowcases by artist John Baldessari, or a window shade from filmmaker Miranda July.

It’s a curious time to be a part of the art world in the San Francisco Bay Area. Mainstream events such as Burning Man—with its nearly 70,000 attendees—have not only presented new ways of encountering art but have softened the distinction between creator and consumer, even as artists struggle to survive the current economy. In the midst of this upheaval, Bay Area–based artists Jonn Herschend and Will Rogan, who conceived and launched The Thing in 2007, have assembled an all-star, interdisciplinary collection of creators to help rethink what art can be. With their limited-edition Quarterly and the September 24 release of The Thing The Book, Herschend and Rogan are bringing “art” to a wider audience—as well as bringing unconventional new sensibilities to art itself.

As Herschend explains, “There’s an element of entertainment to The Thing. It’s exciting to have our stuff operate in between all these worlds in ways that we’re not accustomed to.”

Rogan chimes in: “Liberating is the word. Don’t use the word fresh.” He laughs. “And not superfresh.”

If there’s a shakeup happening in what art is and what it’s supposed to be—as this pair contend—the two artists are well positioned to steer the conversation. Each currently has a successful career as a visual artist. (Most recently, Herschend appeared in the 2014 Whitney Biennial; Rogan had a solo exhibit at the Berkeley Art Museum.) But when they met in UC Berkeley’s MFA program in 2004, both were, unusually, struggling to support a family: Herschend as a high school teacher, Rogan as a librarian.

Despite radically different upbringings—Herschend was raised on an 1880s theme park in the Ozarks, Rogan in suburban Lafayette, Colorado—they quickly discovered shared sensibilities, including a love of videography and photography, an interest in conceptually driven pieces, and a penchant for humor in their work. Most significantly, both thought it would be interesting to start a magazine.

But not your average magazine. The Thing Quarterly, as they conceived it, would be a utilitarian household object, but designed by an artist of some sort, and with an aspect that you could “read.” Herschend and Rogan were inspired in part by the celebrated “junk mail” issue of literary magazine McSweeney’s (which arrived as a rubber-banded bundle of ordinary-looking mail), as well as the deadpan humor of conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s. By the summer of 2007, a year after they’d finished their MFAs, the pair had managed to get San Francisco arts nonprofit Southern Exposure interested in the project. Southern Exposure gave them funding, a temporary storefront, and access to the organization’s extensive network.

The first issue was guest-edited by the filmmaker/artist/writer Miranda July, a mutual acquaintance. Her contribution: a window shade inscribed with the sentence, “If this shade is down I’m begging your forgiveness on bended knee with tears streaming down my face.”

“We anticipated that we would probably make 50 by hand and that would be our subscriber base; and we’d just do it for a year, it would be interesting and fun,” recalls Herschend. Instead, they ended up with 1,500 subscribers and had to scramble to give themselves a crash course in bulk manufacturing.

Seven years later, The Thing Quarterly is about to publish its 24th issue. This time around, the object—a record by the punk band No Age—was conceived by Rodarte designers (and Berkeley alumnae) Kate and Laura Mulleavy. The Mulleavy sisters are just the latest in an impressive string of guest editors that includes both the downright famous and the somewhat obscure, including visual artists, graphic designers, novelists, filmmakers, photographers, and fashion designers. The editors are selected not based on name recognition, but on the outside-the-box qualities of their work. Explains Rogan, “We tend to be interested in people who are working out-of-bounds in their practice.”

“It’s a thrill to work with The Thing,” says regular contributor Tucker Nichols, a visual artist who designed (among other things) a set of beer mats for The Thing Quarterly. “It feels like a very genuine enterprise. Cut out a lot of the workings of the art world, and open up who you define as an artist and give those people a lot of freedom, and what will you end up with? It’s a big experiment.”

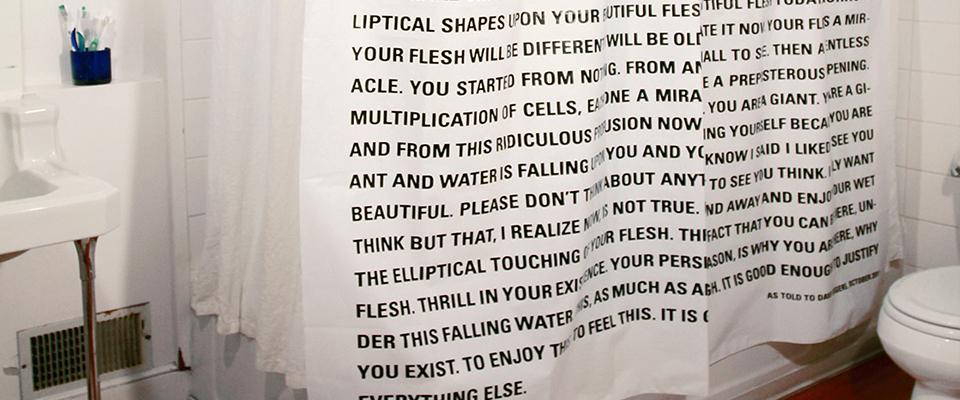

Herschend and Rogan give their guest editors only a few parameters before setting them free. Their object must be functional, it must involve text, and it must weigh less than three pounds (otherwise, shipping gets prohibitive). The results have ranged from a shower curtain inscribed with a monologue by novelist Dave Eggers; to an avante-garde T-shirt by fashion designer Doo.Ri; to a set of ceramic dice with instructions for a game, by artist David Korty.

Some issues of The Thing are tongue-in-cheek, such as a custom tin of Thompson Cream designed by experimental novelist Ben Marcus as “a salve … that can be applied to most any situation.” Others are more sincere (and truly functional), such as a bamboo onion-cutting board that public-radio writer and producer Starlee Kine inscribed with a story of lost love.

“They are able to bring out some of the most interesting sensibilities of these collaborators, in a way that is unexpected,” observes Tanya Zimbardo, Assistant Curator of Media Arts of SFMOMA (which has collected the entire run of The Thing Quarterly). “The collaborations are also very smart: They touch on humor or funny moments, emotional content in some cases.”

Over the years, Herschend and Rogan have also released two dozen limited-edition special projects, ranging from a poster designed by filmmaker and graphic designer Mike Mills, to a handmade “perfect espresso cup” by artist Nathan Lynch. Almost all The Things have sold out, often in advance—despite (or perhaps because of) the mystery surrounding them.

“Part of the lure is that you don’t really know what you’re getting when you subscribe,” explains Courtney Fink, director of Southern Exposure and an early supporter. “It’s a little bit of a leap of faith: What’s John Baldessari going to make?” Equally appealing, she says, is the fact that, for a mere $60 (at $240 for the annual subscription), you can own something made by John Baldessari, whose original work otherwise sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars and up. “Their objects are accessible to a pretty broad community of audiences,” she observes.

Although Herschend and Rogan always intended The Thing to have this kind of populist appeal, it still came as a surprise when the home design community—rather than traditional art collectors—came to make up a core of The Thing’s audience. Objects such as artist Tauba Auerbach’s 24-hour clock and writer Dave Eggers’s shower curtain have landed on cool-hunting lists and been endorsed by interior decorators in The New York Times “Home” section. For the modernist and design conscious, after all, a limited-edition Dave Eggers shower curtain makes a great cool-signifying status symbol.

Still, subscribers are faced with a conundrum every time they open a new brown-paper box: Use the objects, or collect them? Is that Anne Walsh–designed rubber doorstop an actual doorstop, or does it just look like one? As put by actor James Franco (who contributed two Things: a table mirror inscribed with lipstick, and a limited-edition switchblade, both in homage to dead actor Brad Renfro), “Their objects underline the detritus of our world and make us look at it anew.”

Sure. But is it art? Definitions are, perhaps, beside the point. “We are interested in the places in between, things that aren’t comfortable, are a little grey and messy,” explains Herschend. “The person who receives the object has to activate it. It’s their decision of how to interact with it, as opposed to its being in a gallery on a pedestal where you have to interact with it in a certain way.”

“It is what it is,” adds Rogan.

“… That’s why we call it The Thing,” finishes Herschend.

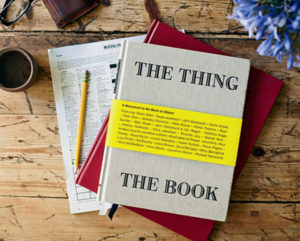

The newest thing is a book published by Chronicle Books. The Thing The Book is almost a meta–art book, its pages a playground for 30 different artists. Each aspect of the book—from the endpapers to the page numbers, the table of contents to the bookmarks—was designed by a different contributor, including author Rick Moody and artist Ed Ruscha. The result is a quirky, contemplative, and tactile homage to print itself.

“Books are disappearing; they are becoming more rarified,” says Herschend. “We like them as physical objects, but they are also a great delivery vehicle. We’re setting up the physicality of the book and asking readers to examine that.”

Printed books may be at risk of obsolescence; but, even more problematically, so are artists themselves. At the same time that the boundaries of the art world—patron and artist, viewer and creator—have opened up, the Bay Area’s astronomical cost of living has forced countless artists out. Lack of interest has helped shut the doors of galleries, institutions, and nonprofits.

As Herschend puts it, “The group of people into art is getting smaller and smaller. Artists have to be involved with the dialogue of how to expand the circle out.”

To that end, not only have Herschend and Rogan created what SFMOMA curator Zimbardo describes as a “new model” for distributing art, they are also fighting to build a stronger arts community in the Bay Area. Each new issue of The Thing Quarterly culminates in a wrapping party: raucous gatherings in which the public is invited to mingle with the guest editors and help assemble and ship the objects. They cohost events with SFMOMA, with Southern Exposure, and with a range of other local arts institutions. They throw “cocktail hours” promoting The Thing’s collaborators. Not surprisingly, people who may not have otherwise attended at an art event are eager to show up when it means wrapping packages alongside James Franco.

Says Fink, “Jonn and Will have jumped to the next level: They are really good at making partnerships and working with people who have broad reach into the fashion, design, and art worlds, tapping into other communities of people.”

The Thing’s regular collaborators, in turn, are getting opportunities that might not otherwise have been possible. For example: corporate work. Having noted the singular aesthetic and appeal of The Thing, companies such as Nike and Levi’s are increasingly coming to Rogan and Herschend for brand consultation.

“It’s an interesting model, that we can pull other people in to think about solving problems for brands,” explains Herschend. For many of their artist contributors, this is a welcome source of income (and survival trumps any antiquated concerns about “selling out”). “In the arts, there are very few people who get to a point in their careers that they make work they can fully live on. I know maybe three people like that. The reality is, you’ve got to find other ways to make a living.”

As for Herschend and Rogan, they no longer have to fall back on day jobs to survive. Instead, the pair find themselves stuck in what Herschend sheepishly refers to as “the busy trap.” Not only are both deeply involved in their own internationally thriving art practices, and regularly teaching at local art colleges, but the growth of The Thing has required them to become entrepreneurs. They must contend with business-related concerns such as production schedules, ever-changing manufacturing partners, and bottom-line costs.

But they know better than to complain. In fact, the word that most frequently peppers their conversation is “exciting.”

Says Herschend, “As long as we take seriously what we’re doing, it’s always exciting when people are interested in it.”

Janelle Brown is author of the novels This Is Where We Live and All We Ever Wanted Was Everything. Her work has appeared in Vogue, The New York Times, and Salon.