An archaeological mystery that called into question the racial history of the Americas has finally been solved. After consecutively assigning him Caucasian, Japanese, and Native American ancestry, a team of scientists including some at UC Berkeley say they have finally determined the geographic origins of the Kennewick Man.

“Kennewick Man” is the skeletal remains of a middle-aged man found on the banks of Washington’s Columbia River in 1996. Carbon dating determined that the bones were roughly 9,000 years old. The discovery attracted attention immediately when the remains were initially declared to be Caucasoid based on skull measurements.

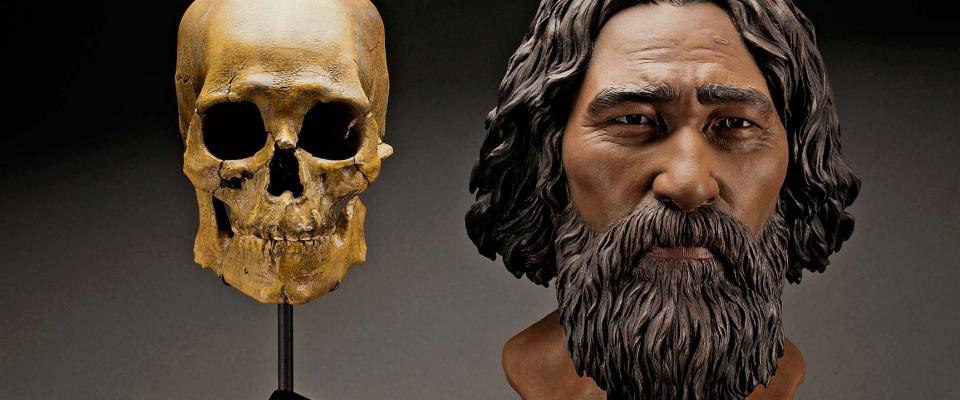

The term “Caucasoid” hearkens back to the 19th century, when many anthropologists classified humans within three racial groups: Negroid, Caucasoid, and Mongoloid. Dated as the term is, some in the public seized on the idea that Kennewick Man was white, suggesting that white settlers arrived in the Americas far earlier than previously thought. The public’s imagination was perhaps spurred by a scientific facial reconstruction of Kennewick Man that bears a striking resemblance to actor Patrick Stewart.

The public’s imagination was perhaps spurred by a scientific facial reconstruction of Kennewick Man that bears a striking resemblance to actor Patrick Stewart.

Subsequent studies suggested that Kennewick Man was more closely related to either Polynesians or the Ainu people of Japan than he was to indigenous North Americans, indicating the early arrival of Asiatic peoples to the continent. Genetic testing now appears to have settled the question of his racial affinity. DNA from a finger bone remnant indicates that his closest modern-day relatives are Native Americans, specifically the Colville tribes of Eastern Washington. (A closer match may be possible, but not all tribes have provided genetic material for analysis.)

The findings, published in the journal Nature in June, undermine the validity of skull measurements in determining race, a practice long questioned by the scientific community. “You cannot assign an individual to a specific geographic group based on skull shape,” says Rasmus Neilsen, a Berkeley computational biology professor and coauthor of the study. Some of the paper’s collaborators studied Native American skulls from similar geographic groups and found that there is too much variation within populations to determine geographic origin for a single skull.

DNA evidence has also complicated an old question: Who were the first Americans? Although Neilsen’s study suggests a single migration, a recent Harvard study found genetic similarities between native Amazonian tribes and aboriginal populations in Australia, New Guinea, and the Andaman Islands. The Harvard study concluded these genes likely arrived with a now-extinct common ancestor in a separate migration.

Meanwhile, Kennewick Man is embroiled in yet another controversy, this one pitting tribes against researchers. “The Ancient One,” as he is often called by Native Americans, faces dueling claims over custody of his bones. Several tribes, including the Colville, want to give him a ceremonial burial; many scientists, however, want to continue studying the remains. In 2004, a group of researchers led by the Smithsonian Institution won a lawsuit against the Bureau of Land Management for the right to study the bones, which now reside in the Burke Museum at the University of Washington and are managed by the government.

Neilsen’s finding may change that. Federal law states that any funerary remains must be returned to indigenous peoples if a “lineal descent or cultural affiliation” is proved. No doubt the results of the genetic testing will renew tribal efforts to repatriate the bones, perhaps finally settling the legal question of whether Kennewick Man will be treated as a revered ancestor or an object of study.

—Natalie Stevenson

From the Fall 2015 Questions of Race issue of California.