I am still trying to wrap my mind around the seductive nature of the 2016 American presidential campaign season. I like the drama, the mudslinging, the tabloid-style coverage, the gaffes, the slip-ups, and the never-ending political commentary from pundits. It’s oddly entertaining, no?

Although, let’s be honest: None of the empty party rhetoric and nastiness can prepare us or the candidates for the realities of elected office. We learned this lesson during Obama’s eight-year struggle to address serious issues while faced with a do-nothing Congress.

Nevertheless, it’s fun to imagine that democracy works. That’s why I voted for Bernie—it was purely a pipe dream. Bernie touted a socialist agenda that bordered on utter contempt for the wealthy class. And I, a product of public schools and a low-middle-class, single-parent African-American upbringing, who got a degree at an Ivy League school before starting this all-too-lengthy stint as a Ph.D. candidate at UC Berkeley, had developed my own contempt for income inequality.

Brushing aside Sanders’s inability to account for how the legacy of racial discrimination intersects with income inequality, one key issue stood out above all else in his campaign: the cost of higher education.

I guess that’s my surprising realization—I voted for Bernie because I love to hate the vast inequalities that still remain in 21st-century America. Brushing aside Sanders’s inability to account for how the legacy of racial discrimination intersects with income inequality, one key issue stood out above all else in his campaign: the cost of higher education.

Nothing defines middle-class status as much as an undergraduate degree. College has become a rite of passage, a means to shore up the status quo or even climb the ladder of middle-class comfort. In the African-American community, the myth that higher education is beneficial is equally strong. I say myth because, at this point, I’m not convinced that the cost of attaining higher education is worth the amount of debt students and their families are asked to shoulder. I voted for Bernie because he addressed those ridiculous amounts of debt.

I used to consider myself rather fortunate. I graduated from Princeton in 2004 with only a few thousand dollars of debt, a sum my mother could easily help pay down. But my doctoral program at Berkeley has been completely different. To offset my department’s lack of funding options and resources, I often borrowed to pay for life in the Bay Area and keep up with my studies. Health problems, stress, and a lack of adequate advising got me deeper into debt.

So when Bernie Sanders claimed both that higher education should be free (for those who meet certain academic standards) and that the federal government should not profit from the millions of student borrowers, I hoped the nation would begin to seriously discuss the myth it helped foment. That discourse is mostly nonexistent. Save a handful of texts such as Andrew Ross’s Creditocracy or David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years, no one has made the links between our current economic crisis and the various types of debt that Americans must rack up in order to live.

Everyone knows there’s something rotten in the state of Denmark, but only Sanders has addressed the myriad issues that point directly to widening income inequality. Yet the connections in Sanders’s argument are still lacking. He likes to rally audiences around the 99 percent vs. 1 percent ratio, but even recent economic studies offer a more nuanced look at the middle class’s diversity.

In his article “Not Just the 1%: The Upper Middle Class Is Larger and Richer Than Ever,” The Wall Street Journal’s Josh Zumbrun notes that recent economic data points to an upper-middle class that has been growing for the past few decades. Members of this elite but sizeable minority can afford expensive college education for their children without a burdensome debt load. Home mortgages are still investment opportunities. Exorbitant rents in metropolitan hubs like the San Francisco Bay Area are an affordable necessity.

The middle-middle and lower-middle classes, however, continue to suffer under a debt load that has become ominous rather than promising. For a significant portion of this middle class population, debt—whether from college expenses, medical bills, or a home worth more on paper than in fact—cannot feasibly be paid off.

So how did we get to this point? The Baby Boomer generation enjoyed job stability, pensions, and suburban home ownership. Today’s Millennials, however, live in a constantly shifting job market with little or no benefits, and they have exchanged a home deed for high monthly rent and college loan payments. And let’s not forget that bankruptcy laws make it impossible for student borrowers to erase that debt through bankruptcy. After all, a bank can’t seize a college degree.

During the past decade, Millennials watched as new-wave satirists like Jon Stewart turned The Daily Show into a sounding board for our general frustrations with a do-nothing Congress. Stewart’s protégé, Stephen Colbert, used The Colbert Report to extend the critique into something akin to performance art by actually running for elected office and giving audiences a detailed look into the shadowy nature of political fundraising.

This election season, Millennials are voicing the same dissatisfaction and frustration as Tea Party and Donald Trump voters, albeit while believing in more egalitarian solutions. We’re distraught. We don’t see our place in America’s future.

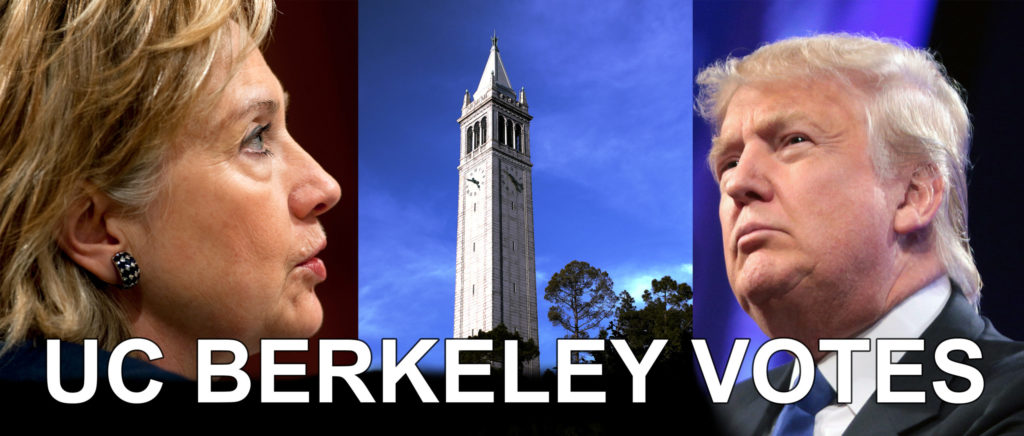

Even now that Hillary Clinton has formally accepted the nomination of the Democratic party and Bernie Sanders has negotiated an impressive second-place finish and watched a grassroots plea become a sizeable influence on the party’s platform, I still wonder if democracy works. Only time will tell.

Khalil Sullivan is an educator, professional musician, and Ph.D. candidate in English at Berkeley.