In 1918, America was at war and students arriving at the University of California in the fall of that year found their campus transformed. From the Center Street entrance, the view of the hills was now obscured by large new barracks and the dark smoke issuing from the powerhouse gave the place the look of a factory. Everywhere young men wore the khaki uniforms of the various military outfits represented on campus—the Student Army Training Center, the School of Military Aeronautics, the Naval Unit, and the Ambulance Corps. “Instead of the college atmosphere which prevailed here before the war,” one student observed, “there has grown up a disinterested attitude which has placed the war before everything else. … To try to start a discussion on anything besides the war, with a view to starting a little ‘California spirit’ has proved futile. The students simply will not respond. Their hearts are not focused on things here at college. They are far away—mostly ‘over there.’”

Yet while the coal smoke and the war in Europe no doubt cast a pall, a still more ominous cloud loomed near, for 1918 was to be a time of plague in Berkeley and around the world, the year of the so-called Spanish influenza. It was called that only because Spain, being a neutral country, did not censor its press to buoy wartime morale; when Alfonso XIII, the young king of Spain fell ill with the grippe, his subjects knew about it.

Even now, no one is sure where the flu originated, although many experts have pointed to Haskell County, Kansas, as a probable ground zero, a district so rural and primitive that many residents still lived in sod houses. A flu epidemic had emerged there in January 1918 that was like nothing ever seen before. Author John M. Barry wrote, “the strongest, the healthiest, the most robust people in the county—were being struck down as suddenly as if they had been shot. Then one patient progressed to pneumonia. Then another. And they began to die.”

In March, a similar epidemic raged through the Army’s Camp Funston (now Fort Riley) some 300 miles away and spread rapidly from there, carried in the lungs of the young conscripts shipping off to the front. In the end, the disease, no doubt accelerated and exacerbated by the war, would have greater reach than the conflict itself, penetrating as far as Asia and Africa, Europe and South America, the Pacific Islands and the Arctic.

It came in waves, abating in the summer, then spiking again in the fall in even more virulent form. It did not arrive in Berkeley until October 6, when two “flying cadets” on furlough from the East presented to the infirmary with flu-like symptoms, chief among them prostration. The flu knocked people off their feet. At the same time, several students were admitted to the women’s infirmary with similar ailments. Within a week, 68 people on campus had fallen ill. In two weeks, the number had climbed to nearly 500. Seven had died. The infirmary was overwhelmed and other campus buildings, including Harmon Gym, Stiles Hall, and even the Zeta Psi fraternity house, were turned into makeshift hospitals. The University physician himself fell ill and had to be replaced by an Army doctor for the duration of the outbreak. “In quick succession,” he would later report, “the worst epidemic in our history was upon us.”

In fact it was one of the worst pandemics in modern history, killing more people in 24 weeks than AIDs would in 24 years. It infected one-third of the world’s population, and global death toll estimates range from 50 to 100 million. In the U.S., the flu cut the average lifespan by 12 years, from 51 to 39.

Most died of pneumonia, a bacterial infection that attacked flu-stricken lungs, but the flu itself could kill outright as well—and quickly, often just a few days after the onset of symptoms. These included the usual—cough, fever, headaches—but also severe hemorrhaging. Patients often bled from their ears and nose. Their lungs filled with a bloody froth and their skin changed color as oxygen failed to circulate through their airways. Some called it the blue death or the purple plague.

The flu killed both high and low, young and old. It killed migratory workers in their camps and soldiers in the trenches. It swept immigrant communities and elite college campuses. It killed the painters Egon Schiele and Gustav Klimt. It took the life of George Freeth, the father of modern surfing. It killed the president of Brazil, the prince of Sweden, and the queen dowager of Tonga. It killed Frederick Trump, Donald Trump’s grandfather, and Phoebe Hearst, the great patroness of the University of California.

Most troubling of all, it killed those in the prime of life. Charted on a graph, the usual mortality curve of influenza epidemics traces a U-shape, with most deaths occurring among the very young and the very old. In 1918, the curve was W-shaped, with a pronounced peak among those ages 20 to 40.

In weekly letters home, sophomore Agnes Edwards Partin tried to ease her parents’ fears. “Don’t worry about me catching the influenza,” she wrote on October 19, 1918. “The kids call it the floo or the flooey. It seems to have gone all over the country. We’ve been expecting to have them close the University … instead of that we are going to have to wear a sort of mask made of gauze that goes on over your nose & mouth—craziest looking things. … Quite a few of the students have it, but … they think it is checked now. … the house has been like a hospital all week.”

Alas, the flu was in full career. “We didn’t have any meeting last Monday night because so many girls were sick,” Agnes wrote in a subsequent letter. “I didn’t tell you about it till it was over because I didn’t want you to worry. Wouldn’t tell you now, but there isn’t anything else to write about.” For weeks, the letters mixed this kind of stiff-lipped optimism with down-at-the-mouth laments. As the flu progressed, theaters and movie houses were closed and even church services were suspended. The only thing to do, Agnes complained, was to study or walk in the hills.

Masks were ordered to be worn in all campus buildings and only removed outside. Shirkers could be arrested and fined, but even then compliance was not universal and indignant letters filed into the student newspaper about “mask slackers” who insisted on “evading the law in every possible way as though it were a sign of superiority to disregard it.”

University President Benjamin Ide Wheeler’s decree on the matter was published in The Daily Californian on October 24. The notice advised students to boil their masks nightly and to keep a receptacle for the mask, which should also be boiled or destroyed. It grew more urgent as it went on, finally blaring in bold text and capital letters. “Act intelligently and do not become alarmed. FEAR reduces your resistance. … KEEP AWAY FROM ALL CROWDS. AVOID STREET CARS … DO NOT ATTEND PARTIES OF ANY NATURE … GO TO BED AT ONCE if you feel sick … INFLUENZA IS A PERSONAL CONTACT DISEASE.”

Precisely for that reason, the most successful response to the flu was quarantine. Sailors on Yerba Buena island, placed under strict quarantine by the Navy, had no reports of flu during the entire outbreak. An even more stark illustration came from the islands of Samoa. American Samoa, placed under quarantine, suffered no deaths from flu in 1918. By contrast, Western Samoa, with no such restrictions, lost 20 percent of its population to the scourge. Of course, islands, whether in San Francisco Bay or the wide Pacific, are one thing, a college campus is another. A vain attempt was made at Berkeley nonetheless: The Student Army Training Corps’ members, while they could mix freely on campus, were ordered not to leave University grounds.

Masks remained the campus’s main response. University women, led by Lucy Stebbins, the dean of women, mass-produced more than 20,000 gauze masks that were distributed from booths around campus.

Agnes wrote home, “After we’ve washed dishes we’re going to the Red Cross rooms & help make the gauze masks. Everyone is going to have to wear them tomorrow, even the aviators. The campus will surely be a funny looking place. I don’t think they do any good myself, but maybe they do.” In fact, it’s not clear that they did. Comparisons of populations that were required to wear masks and adjacent populations that were not showed little difference in health outcomes.

With so many taken ill, a breakdown in public services at times must have seemed imminent. At the height of the pandemic in San Francisco, then a city of half a million, 600 telephone operators were absent with flu, 7 policemen had died, 85 firemen were sick or recovering. Garbage piled up in the streets as sanitation crews were hobbled by the disease, and San Francisco Hospital announced there wasn’t room for a single additional patient. The normal death count per month in San Francisco was 630. In October 1918, the number was 1,826. In Oakland, bars closed down for lack of clientele and prison chain gangs were used to set up hospital beds and dig graves.

It wasn’t just big population centers that were afflicted. On October 10, the little railroad town of Dunsmuir near Mount Shasta reported that 30 percent of its 1,000 residents were down with the flu and 5 had died in just 24 hours. When Agnes Edwards sent her letters home to the Imperial Valley, the flu was waiting at the receiving address. She was pained to learn that the mailman had fallen ill and that her parents, not owning a horse and buggy, had had to walk to the post office to retrieve her letters.

People fell back on whatever home remedies they could to ward off the worst. Berkeley resident Amelia “Minnie” Stone sent regular correspondence to her son Max, a University of California alumnus fighting with the Expeditionary Forces in Europe. In a letter that October, she wrote, “We are trying to keep as well as possible, and if we feel the slightest symptoms, use powdered boracie [boric acid] snupped up the nose, hot mustard foot baths, a dose of salts, etc.. and it has done the work so far.”

Statistics only serve to obscure the true depth of the tragedy, as some individuals must have experienced the epidemic as a kind of personal Armageddon. Professor Walter Steilberg survived the flu, but lost his wife, his mother, and his infant daughter to the epidemic.

Stone wrote to her daughters, “I always think of a song Ferris Hartman used to sing, ‘I had a little bird whose name was Enza, I opened the door and InfluEnza [sic]’! and wish he had not opened the door!!’” The grim little ditty was apparently making the rounds. Like “Ring Around the Rosie,” children chanted it as they skipped rope.

As the conflict overseas raged on, the California Alumni Fortnightly (a precursor to this magazine) documented the university’s war contribution. The October 1, 1918, issue listed “3,073 Californians” in uniform. Death notices ran in every edition under the heading “Pro Patria Mortui.” As if the horror could be managed by rationing, the deaths were meted out, eight fallen soldiers per issue. Scanning them now, it’s clear that germs were doing at least as much damage as the Germans. For every soldier killed in action, another died of the flu or pneumonia or unspecified disease. Many never made it overseas. Historian Alfred Crosby observed that not a single troopship carrying American soldiers was sunk during the war, but that the “doughboys had a much deadlier enemy than u-boats which they brought on board in their own tissues.” He estimated that, in just the last two months of the war, at least 4,000 American soldiers died in transit.

Throughout it all, insurance salesman Howard Leggett, Class of 1909, was one of the Fortnightly’s most reliable advertisers. “Leggett Will Care for Me,” his slogan ran. “And the cost is less than your average cigar bill.” When it seemed the flu might have finally passed, Leggett preached, “The Uninsured in the Nation are having a graphic lesson in Life Insurance. SPANISH INFLUENZA has emphasized the uncertainty of life and the consequent ever-present need of Life Insurance Protection.”

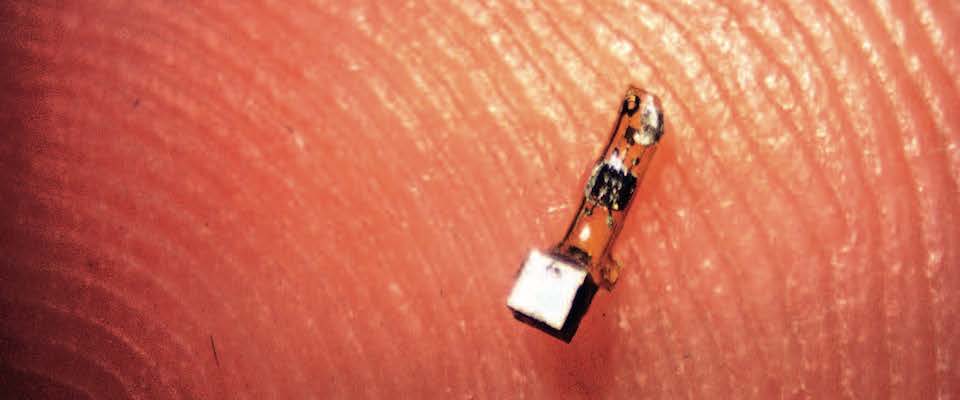

As with all flus, the microbe that caused the pandemic was a virus. In 1918, the germ theory of disease was almost universally accepted, but while viruses were known to exist, no one had ever seen one for the simple reason that they are too small to be visible under an optical microscope—about a hundred times smaller than most bacteria and about a thousand times smaller than the average human cell.

While we regularly speak of “live virus” and “killed virus” vaccines, biologists will tell you that viruses are not really living at all. Exactly what they are—neither quite live nor dead—makes them difficult to talk about. “The language is obviously inconsistent,” admits Berkeley epidemiologist Arthur Reingold, “but if you say that viruses are in fact alive despite what the biologists say, then viruses can survive and remain infectious outside the cell … on doorknobs or whatever—certain viruses depending on temperature and humidity. But they can’t replicate. For that they need a cell.” That’s the key distinction when talking about viruses says Reingold, “survival versus replication.”

Under an electron microscope flu viruses are revealed to be generally spherical in shape. The virions, as virus particles outside a cell are called, consist of a nucleic acid core enclosed in a protein coat that is spiked with glycoproteins—specifically, hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. These are the familiar H and N used to describe the various subtypes of flu. (Today we know that the 1918 flu was of the type H1N1.) These proteins are often described as the keys that allow the virus to, first, penetrate the cells, and later, to make their escape. One key to get in, another to get out. While inside, the invaders hijack the cell’s machinery to replicate themselves, creating a whole army of viruses to attack us.

Thankfully, our cells are not defenseless. In fact, a battle is constantly being fought between our immune systems and the invading pathogens. If a virus is familiar to our bodies, our white blood cells swiftly produce antibodies to block it. If not, it can take days for our cells to marshal an adequate defense, which may be too late.

But as the flu virus replicates it also mutates; many small mistakes are introduced in the genetic code, which then slowly accumulate and respond to selective pressures. This type of evolution is called antigenic drift, and if the genes drift far enough, a novel strain will form—one our bodies no longer recognize. It can also happen more quickly, via a process called antigenic shift, which involves a reassortment of genetic material. Such shuffling of the viral deck can happen in other species that harbor flu, including birds and swine, and be transmitted to humans with deadly results. This constant mutation of the flu virus explains why a new vaccine is required every year.

The precise evolutionary history of the 1918 flu virus remains a mystery to this day, even though, in the late 1990s, scientists managed to retrieve and sequence its DNA from preserved tissue samples housed at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology as well as samples exhumed from a mass grave in Brevig, Alaska, an Inuit community in which more than 80 percent of the population perished from the flu.

Unfortunately, the genome has so far failed to provide answers as to why the 1918 flu was so deadly and why it preferentially killed the young and healthy. One speculation, says Arthur Reingold, is that “the elderly probably had been exposed to … and were therefore immune, or partially immune, to a similar virus that may have circulated in the 1880s.” Even if that were true, he stresses, it still wouldn’t answer the question of why the very young also fared better than the young adult population.

Sometime after midnight on November 11, 1918, Agnes Edwards was awoken by the “awfullest noise” and went shivering out onto her porch in her nightclothes. “The University power plant blew for about 2 hours & the fire department was out, & everyone had horns & cowbells, & the girls went down & got our Chinese gong, & pounded & pounded.” It might have been the end of the world, but it was only Armistice Day. The war was over.

The flu was not quite vanquished however. The virus waged a final campaign that winter. In a letter dated January 4, 1919, Edwards wrote, “As I was coming up the walk I heard the phone ringing madly, so rushed in—Mrs. H. never hears it. It was Virginia & she said college wouldn’t open for another week because the Flu was starting in again, & she wanted me to wire the girls so they wouldn’t come. Well, that news was certainly a shock. I sent ten telegrams—all collect, naturally.”

Thankfully the resurgence would be short-lived, and the February 1, 1919, issue of the Fortnightly carried the headline “The Influenza Declines.” The infirmary was still filled, but the expected onslaught of new cases had not materialized. And while spring semester had been shortened to 19 weeks “due to the prevalence of influenza,” the “mid-semester recess” was abandoned to make up for lost time. The troops were demobilizing and a return to normalcy was wistfully hoped for. By April the disease was gone. As with the war, the curse had somehow lifted. Out flew Enza.

In the June 7, 1919, issue of the Fortnightly, the final war tally was given: 99 alumni had died, 21 in accidents, 35 in action, 43 “of disease.” As for campus, of the estimated 1,400 who had taken ill with flu, 21 died, including 1 faculty member and 2 student nurses. Such statistics only serve to obscure the true depth of the tragedy, however, as some individuals must have experienced the epidemic as a kind of personal Armageddon. Professor Walter Steilberg survived the flu, but lost his wife, his mother, and his infant daughter to the epidemic.

Cal’s Memorial Stadium was built in 1923 to honor the Californians who fought and died in the Great War, and another memorial to the fallen, a marble bench, gift of the Class of 1920, greets visitors to the Campanile. But a century after the great flu of 1918, a visitor to campus will search in vain for any physical monuments to commemorate the plague’s victims or those who fought against it—that other war, which killed more people than died in combat in the Great War and its horrible sequel combined.

Traces of the flu’s legacy can still be located in the library, however—in the letters of Agnes Edwards Partin and Minnie Stone, and in the pages of countless books. The 1918 flu figures in novels such as Thomas Wolfe’s Look Homeward, Angel, Wallace Stegner’s Big Rock Candy Mountain and William Maxwell’s They Came Like Swallows. It’s the central theme of Katherine Anne Porter’s beautiful, fugue-like novella Pale Horse, Pale Rider. “It’s as bad as anything can be,” a soldier in that story says of the flu. “All the theaters and nearly all the shops and restaurants are closed, and the streets have been full of funerals all day and ambulances all night.” Porter’s title comes from a passage in the Book of Revelation about the fourth horseman of the Apocalypse. “And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death….”

The literary legacy of 1918 may also be found in another, less obvious example. Berkeley English professor and bestselling author George R. Stewart survived the 1918 flu while serving in the Ambulance Corps, but according to his biographer Donald Scott, he never fully recovered, eventually losing a lung to the effects of pneumonia. Today, the prolific Stewart may be best remembered for Earth Abides, his 1949 novel, set primarily in Berkeley, about a pandemic that wipes out civilization.

Although Stewart never named the disease at the heart of his imagined apocalypse, the description sounds hauntingly like influenza. “It might have emerged from some animal reservoir of disease; it might be caused from some new micro-organism, most likely a virus, produced by mutation; it might be an escape, possibly even a vindictive release from some laboratory of biological warfare.” In his 1978 novel, The Stand, Stephen King, who acknowledged a debt to Earth Abides, took that last premise and ran with it to some very dark places. Stewart was less cynical. His book may be unremittingly apocalyptic, but it did not despair of the human race. Perhaps recalling how America had reacted in 1918, he could only imagine that society would acquit itself nobly in the end. “Civilization had retreated, but it had carried its wounded along, and had faced the foe.”