If you ever owned an old air-cooled Volkswagen, chances are you also owned a copy of the “Idiot’s Guide,” or at least knew about it. Its real title was How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive: A Manual of Step-by-Step Procedures for the Compleat Idiot “with complete spelled wrong on the cover,” one joker put it, “so you know it must be good.”

Self-published in 1969 by John Muir, who got a Berkeley civil engineering degree in 1951, the book was regularly touted in Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog and soon gained a cult following with youth across the country. In December 1971, the Chronicle of Higher Education listed the bestselling titles from the Princeton University bookstore. Muir’s manual was number four, falling somewhere between John Updike’s Rabbit Redux and Carlos Casteneda’s Separate Reality.

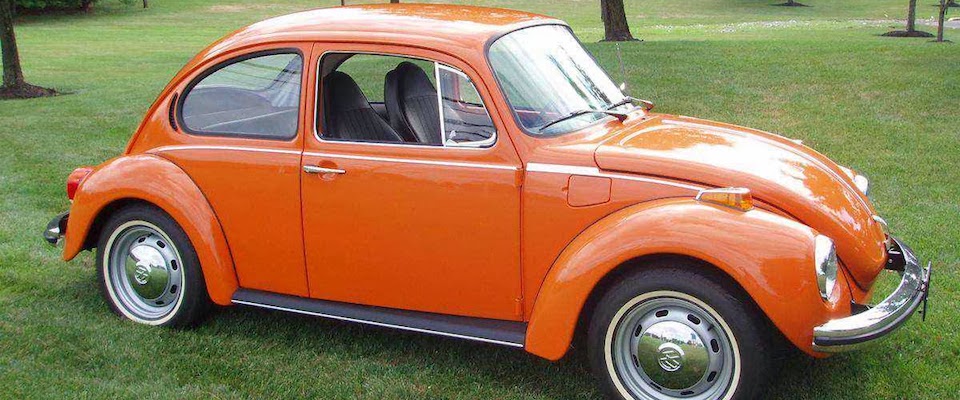

Indeed, long before the “For Dummies” books became a thing, the Idiot’s Guide, as it was generally called, sold millions of copies, mostly to hippies and their ilk—vagabonds and rucksackers and communards and back-to-the-earthers—who tended to favor the cheap German imports over the Detroit behemoths. Putting aside Further, Ken Kesey’s International Harvester school bus, no vehicle is more emblematic of the ’60s counterculture than the VW Bus and its compact cousin, the Beetle, aka the Bug.

Part of the appeal was their simplicity. Air-cooled as opposed to water-cooled, they were stripped down, free of radiators and hoses and water pumps. Their engines were also comparatively small and could be easily dropped out of their rear compartments and either overhauled or swapped out for a new one. You could keep one going forever if you knew what you were doing. The problem was that you needed to. Underpowered and prone to overheating, the cars needed a good deal of maintenance, including regular valve jobs. Neglect that duty, and you were liable to throw a rod and find yourself stranded.

Of course, the flower children were not exactly renowned for their mechanical acumen. If anything, they tended to view machinery with suspicion and dread—the root of all our Cold War nightmares. That’s where Muir, the mechanic, came in, to ease their minds and show the way—not so much John of the Mountains as John of the Grease Gun.

A posthumous profile of the man (he died in 1977) that appeared in a 2002 edition of American Heritage’s Invention & Technology magazine, cast him as a bridge between the young, technology-averse Aquarians and the tech entrepreneurs to come. The article’s author, Paul Ceruzzi, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum, wrote that Muir’s book “let an entire generation reconcile itself to an activity it saw as fundamentally square and middle-class. The Idiot Book helped the youth of the 1960s get over the notion of technology as a big, monolithic, malevolent force and understand it as a set of tools that can be used for good or bad or both.”

That may sound like a stretch at first, but the thesis is compelling. After all, Steve Jobs reportedly stated that he wanted his personal computer to mimic the style of the VW Beetle, so it would never go out of fashion. To raise funds to get Apple off the ground, Jobs sold his VW Bus for $750. And the influence has arguably worked both ways: whereas the old Beetles looked more like cockroaches, designed to survive a nuclear attack, the New Beetles (not so new anymore) look like a missed branding opportunity, like iBugs.

But getting back to our hero: John Muir, who some sources say was a relative of the famous naturalist, was born in 1918. That made him old to be a hippie. And yet a hippie he was. When he married for the third time in 1968, the entire Hog Farm commune attended, including Wavy Gravy, the DayGlo jester. After graduating from Berkeley, he worked in aerospace, including a stint at NASA, but eventually dropped out and found his way to Taos, New Mexico, where he set up a repair shop called John’s Garage. It was there, and in Mexico’s San Miguel de Allende, that Muir set to writing his manual, which he filled with soulful, folksy advice on everything from buying a car (assume the lotus position and meditate before taking the plunge) to how to drive (never, ever lug the engine) to step-by-step instructions for doing a complete engine rebuild. When it was finished he recruited Taos-based artist Peter Aschwanden to illustrate the text with whimsical, R. Crumb-inspired drawings. It was a perfect pairing, like Hunter S. Thompson and Ralph Steadman, and helped cement the book’s countercultural appeal.

The guide not only sold, it got used. Untold thousands of Beetle, Bus, and Karmann Ghia owners rebuilt their VW engines with their oil-stained Idiot’s Guide open on the floor beside them, Muir counseling from the page to avoid both shortcuts and long cuts alike. On the page, he came off like Ram Dass with a spark plug wrench, Arlo Guthrie in coveralls.

And while most of his counsel made good sense (Don’t overtorque bolts, drive your bus like you were strapped to the front of it), some of it was plain wrong (he told VW owners to warm up their cars for a full 10 minutes, something everyone from Click and Clack to the manufacturer have said is bunk), and some of it was pure woo-woo. “Feel with your car … Use all of your receptive senses … the type of life your car contains differs from yours by time scale, logic level, and conceptual anomalies but is ‘Life’ nonetheless.”

That animistic streak was also part of the guide’s appeal. In his book Bug: The Strange Mutations of the World’s Most Famous Automobile, author Phil Patton observed that “In Muir’s book, the Bug came alive in a different way than in the Herbie movies. Like any experienced engineer, he knew that mechanisms were full of aberrations in behavior, gremlins and glitches—bugs.”

Muir himself preferred to see the cars as beasts of burden; specifically, donkeys. The epigraph of the Idiot’s Guide runs, “Come to kindly terms with your Ass, for it bears you.”

Muir died 40 years ago, in Agua Fria, New Mexico, but even now, long after the last air-cooled Bug rolled off the assembly line, his book is in print. The 19th edition is available from Avalon Travel, a Perseus imprint headquartered in—where else?—Berkeley.