The latest news from our quarterly columnist

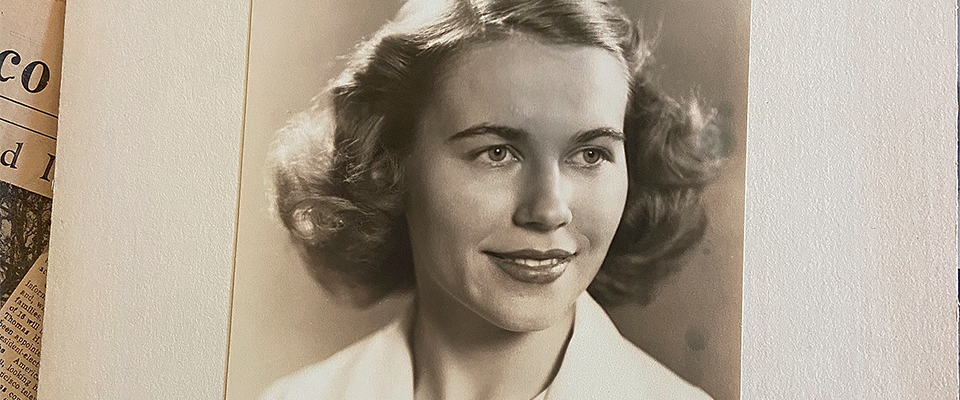

BECKY WHEELER ’49 DIED ON APRIL 9 in the home where she grew up in Walnut Grove on the Sacramento Delta, one month shy of her 94th birthday. One of her final wishes was to see Cal one last time, so her daughter and son-in-law, Caroline Perkins ’84 and Tadd Perkins ’83, arranged for her to have a virtual tour of the campus.

“She started at Sproul Hall, which was called the Administration Building back then, and the Student Union, which, of course, hadn’t been built yet when she was there,” says Caroline. “Then she went through Sather Gate, past Dwinelle—which wasn’t there when she was, either—and Wheeler to Doe Library, where she and I spent many happy hours in the Morrison Room. Then she stopped by the Campanile and finally ended up at the Big C.”

The Campanile was a bittersweet memory—the place where she last saw her college boyfriend before he left for the war the next day.

“The way she told it, just as he was leaning in to give her a kiss and ask that special question, her parents stepped out from around the corner. They were kind of spying on her. They whisked her away, leaving that poor boy standing there. She told me, ‘That was the meanest thing I’ve ever done.’ She was so cross with her parents, but she was a dutiful daughter.”

After the virtual tour, Caroline kissed her mom goodbye. The next morning, she got a phone call from Becky’s gardener, who was in tears. He said Becky had died peacefully in her sleep. That campus tour was one of the last things she ever did.

Becky was born on May 8, 1927, the third generation of her family to go to Cal, starting with her great-grandfather, Arthur McArthur Seymour, who graduated in 1891 and holds the distinction of being the first person ever to turn down the prestigious University Medal. “He thought others were more deserving,” Caroline says.

Becky Wheeler was born Dorothy Beck, but at Cal her sorority sisters in Kappa Kappa Gamma dubbed her Becky, and the nickname stuck. After graduating from Cal, she became the society editor of the San Francisco News and one of the first television columnists in the Bay Area.

While covering the Bachelors’ Ball on assignment from the newspaper, she met her future husband, Bill Wheeler. “She turned him down three times and then he was the love of her life,” says Caroline. They wed in 1953, had three daughters—all staunch Democrats, like their mother—and stayed happily married until his death in 2004. “We just found all their love letters, which is super fun.”

She was a committed local activist, working to protect the community and environment against high-rise development and freeway construction, co-founding the West Pasadena Residents Association in 1962. After Bill retired, they returned to Becky’s family home in Walnut Grove, and she threw herself again into civic engagement.

“One of the first things she’d ask you was, ‘So what are you doing with your life?’ ” says her son-in-law, Tadd. “What she really meant was ‘What are you reading?’ ‘Where are you volunteering?’ and ‘What shared friend did you last see?’ ”

“She never missed voting in an election, and she was especially happy to live long enough to cast her last vote for Biden,” says Caroline. “She also helped me address more than 1,500 envelopes to send get-out-the-vote messages to voters in the swing states.”

When she died, her family buried her ashes under an oak tree, said her favorite prayer, and sang her favorite song, “Hail to California.”

“It was the only song that made her smile and cry at the same time,” says Caroline.

MOVE OVER, MISS MANNERS. Sarah Kidder ’05 is the new etiquette guru in town—and her expertise covers much more than which fork to use. Sarah learned about etiquette literally at her mother’s knee. “My mom ran a successful flower business and incorporated etiquette into much of her work. This opened my perspective about what manners really do for us, and influenced the course of my life. Etiquette was threaded into the whole of my education at Cal, especially my folklore class with Professor Dundes and my English lit classes with Professor Breitwieser.”

After her mother died 21 years ago, she took over the family business and expanded it to include teaching and writing about etiquette and producing big events such as the monthly Oakland “First Fridays” street festival, the annual “Bike to Work Day Bike Happy Hour,” and the San Francisco Education Fund’s “Tipping for Teachers” celebrity waiter event.

She also coaches private clients, ranging from CEOs to women transitioning from incarceration back into society.

“Women in rehab facilities are looking to start over, and they wonder, ‘How am I going to get a job? How am I going to make new friends?’ I tell them they already know many of the answers but don’t realize it. The way they made it through prison included showing respect, and etiquette is all about respect.”

I couldn’t let her go without some Etiquette 101: How do you make a good apology? How do you write a letter of sympathy? And, yes, how do you know which fork to use?

First, the apology: “Own what you did wrong and apologize for it. Period. Don’t try to explain, and don’t make excuses. In short, don’t make it about yourself. If you like, ask for forgiveness, but give them time. And please, please, please say, ‘Please.’ ”

Next, the sympathy letter: “Don’t make it all about yourself. The tried-and-true statements—‘My deepest sympathies,’ ‘My thoughts are with you,’ ‘My sincere condolences’—are always a safe bet, especially if you didn’t know the person who passed well. That said, when possible, it’s nice to add something positive about the person who passed—about their warm smile, the way they lit up the room, or how much you will always love them.”

And finally, the fork: “Unlike many things in life, etiquette is not here to stump you. If a table is properly set, there will only be utensils on the table that you need to use for the meal that you’re having. You go from the outside in. The first utensils you’ll be using will be on the perimeter of your place setting. Think of utensils as breadcrumbs, like Hansel and Gretel. Remember, forks are not here to embarrass you. It’s actually harder to use the wrong fork than you think.”

As expected, Sarah ended our interview with her favorite phrase, “Thank you.”

WHEN KATE ROGERS ’09 ARRIVED ON CAMPUS freshman year, she noticed something was missing: Here, in the very heart of California cuisine, there was no cooking club! So she decided to start one.

She made friends with local chefs, invited them to campus to teach cooking classes, and led her club members into nearby restaurant kitchens to learn from the experts. The first year was a great success, and by year two she decided to take things up a notch. She organized “The Big Cook-Off” between Cal and Stanford, with the mayors of Berkeley and Palo Alto among the judges. (Cal won, of course.)

By Kate’s junior year, the Cal Cooking Club had mushroomed to more than 600 members, making it one of the largest organizations on campus. So, with encouragement from celebrity chefs like Alice Waters ’67 (with whom she interned at Chez Panisse during senior year) and Jamie Oliver, as well as food writer and Cal journalism professor Michael Pollan, she decided to expand to the larger community, stepping down as the campus club’s president to found an off-campus club for children, which she named the Sprouts Cooking Club.

“Working for Alice Waters taught me scads of lessons. She didn’t hesitate to take your hand or look you directly in your eye as she spoke. At lunch, she was adamant that everyone sit together, from the dishwasher to the office secretary to the line cooks. Here at Sprouts, inclusivity is also of the utmost priority.”

Sprouts is a year-round operation, where children and young adults learn everything it takes to eat and live sustainably, including butchering whole pigs, making aioli from scratch, and the trick to the perfect stir-fry. They have made butternut squash ravioli at Boulevard and French cuisine at La Folie, and deboned chickens at Nopa.

In summertime, the local apprentices are joined by out-of-towners who come from as far away as New York, Los Angeles, and Hawaii. They’re able to beef up their résumés (pun intended), get entry-level jobs, and, best of all, find a real passion for cooking.

So what sparked Kate’s passion for food? Her mother.

“I think my first fascination with food stemmed from curiosity. My mom magically put dinner on the table for our family of nine, and I had no idea how she was doing it. So I decided to learn how to cook so I could unravel this mystery. My first creations were pretty hairy. I remember pizzas with Tootsie Rolls, all sorts of combinations that didn’t really make sense. And then, little by little, I started to learn enough skills that I could make simple dinners for my family.”

Like the restaurant business itself, Sprouts had to adjust to keep up with events after the pandemic struck last year.

“We decided to offer our virtual coaching classes to youths all across the nation. And we are really, really having fun because it’s allowing us to connect with chefs from literally all over the United States and do meaningful, fun, affordable, simple recipes that kids from any state could create on their own at home for their families.”

“I think kids are having a really hard time with COVID, and the amount of depression and anxiety has skyrocketed with the amount of time at home and also the time away from school. We’re really excited about these classes because it’s a little beacon of light in otherwise grim settings. And it’s also a way for chefs who have closed down restaurants, or are in a transition with their careers, to give back to kids, and I think that’s really special.”

Reach Martin Snapp at catman442@comcast.net.

From the Fall 2021 issue of California.