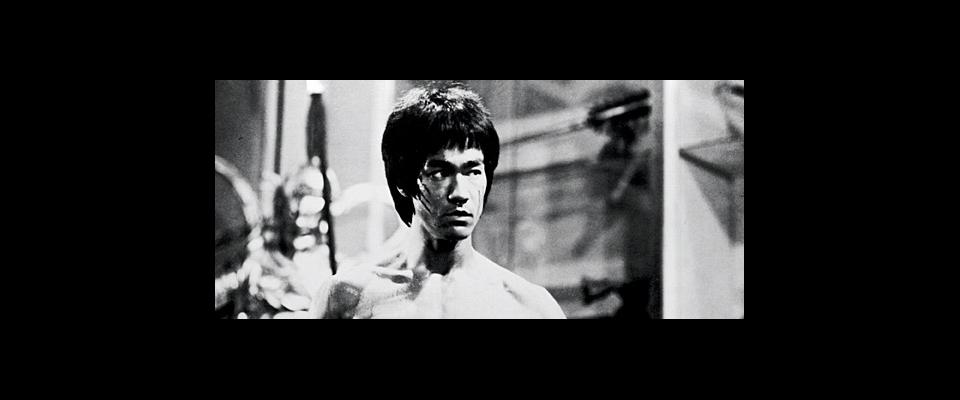

When Bruce Lee first flew like an avenging god across the silver screen with his awe-inspiring kicks, he redefined cinematic action and brought the heroic Asian male onto the world stage.

Picture this sun-drenched memory: I am five years old, in white pajamas, and swinging on a hammock. On the flame trees the cicadas are humming, but I’m not entirely there in the Mekong Delta. In my hands is a thick picture book. I’m on a quest with Monkey King, Pig Monster, and the half-water demon, Sha Wujing, as they search for their kidnapped master in Journey to the West—my first martial arts, magic-endowed epic.

That well-loved 16th century yarn came down from far up north—an equally mythical country called China. Besides Confucianism and Chinese New Year (which we called Tet), China gave me clashing swords, flashing silk brocades, and demonic fighters dancing on mountaintops. For many childhood siestas, my imagination would not let me sleep.

Picture then another memory: I am nine and being driven to school in an army jeep in Saigon. But today the street is filled with weeping young men donning white headbands. On their shoulders sits a garlanded altar. My jeep draws near. Bruce Lee’s handsome face stares out from the altar with determination and seriousness. Asia’s most famous son had died a few days earlier while making a film in Hong Kong. I, too, begin to cry.

Every schoolboy I know loves Bruce Lee, and I am no exception. At school, the older boys often say, “Little Dragon Lee shows the Americans and the French how to fight, and what honor really is.” Through Little Dragon Lee, we can imagine our own faces on the silver screen. Never mind that Vietnamese saw China as a traditional enemy. Lee transcended race and national boundaries. In the schoolyard many of us, after having seen a Bruce Lee movie, would pretend to practice martial arts. We would fight each other under the shade of the tamarind trees, and repeat certain lines learned from the film, and echo that famous Bruce Lee high-pitched growl to unnerve our opponents. Lee single-handedly brought the heroic Asian male image, long suffering from invisibility, onto the world stage, restoring Asian pride. How could I not weep at his passing?

And this, alas, is my Vietnamese close-up: I am 11. Communist tanks roll into Saigon. An inveterate bookworm, I read quickly the last pages of Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils, written by that most famous of all Wuxia (martial arts) novelists, Jin Yong, whose prolific work inspired several generations of filmmakers and comic book artists across Asia. I toss the book back through the car’s window, grab my backpack, and wave goodbye to Uncle Phuoc, the family chauffeur, and board the C-130 cargo plane with my mother, sister, and two grandmothers to begin our lives in exile. On the plane heading toward Guam, amidst weeping refugees, my head remains full of dueling villains and heroes as my homeland beneath me gives way to a vast green sea. Mythical, magical China accompanies me on my own journey to the other West: The wild, wild West.

But the America that received my family and me in the mid-’70s had not yet fathomed the dawning of the Pacific Century. And if Bruce Lee with his swift kicks, furious punches, and energized grunts made a dent in the American imagination, he died too soon. He did not save me from the taunts of the neighborhood kids. The blond teenagers who played softball and skipped rope on Mission Street in San Francisco mocked my three cousins and me as we tried to live our childhood kung fu fantasies in the backyard of my parents’ new home. We knew all the lore of martial arts epics: the right acupressure could paralyze one’s enemy; the antidote to the deadly flower from the Cave of Desperate Love was the poisonous sting of a certain bee; Wu Tang Clan’s secret fighting manual would teach you to soar above the treetops and to run on the surface of water. The “iron palm,” the “dragon stance,” the “six-median sword energy”—this was the language of our childhood wonders. But it was not yet a shared language, and it fell mostly on deaf American ears. “How can you paralyze someone with just a finger; that’s just so stupid,” our young neighbors would jeer over the fence when we tried to explain the great power of various kung fu techniques. Embarrassed, we took our mock kung fu fighting, our heroic quest in ancient China, into the safety of the garage, hidden from neighbors and the glaring California sunlight.

Until recent times, Asian immigrants in America were largely cut off from the narratives of their home continent. News and images from home barely trickled in. A letter from Vietnam took months to arrive. A newspaper from Hong Kong took days to reach San Francisco. Out of nostalgia, my cousins and I would sometimes venture to the Great Star Theater, that dingy, moldy barn on the edge of San Francisco’s Chinatown, where kung fu movies were the daily staple. Back then, the stories of revenge and blood debts and the hero’s agonizing endurance to learn martial arts in order to restore his clan’s honor could be seen through a few art houses, and, increasingly, through the new invention called the VCR, into which we slipped a videotape from Hong Kong to watch the old Wuxia epics unfold in our own home, while we dreamed of a lost continent.

But let us fast-forward a couple of decades or so. For here is yet another kung fu moment: Michelle Yeoh and Zhang Ziyi are dueling with mind-boggling martial arts skills from one ancient rooftop to another, a steady drum beat egging them on. Fists and feet fly, elbows and knees clash, bodies flip backward and sommersault, and the excited audience at the Sony Metreon Cineplex in San Francisco murmurs its collective approval. When that scene is over, the audience erupts in clamorous cheers. It’s Ang Lee’s film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, of course, an American production, mind you, filmed entirely in Mandarin but shown in thousands of major theaters across the United States—a first. Lee had rendered sophisticated and elegant an old genre, lifting it above its often “chopsocky,” low-budget predecessors, to the level of poetry. The movie was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including best picture, and won four Oscars, for best foreign language film, best original score, best art direction, and best cinematography.

I confess, watching the audience’s enthusiastic reaction is like seeing my own childhood fantasies emerge finally from my parents’ dusty garage to spill irrevocably into the public sphere. I feel proud and excited, but there is also this nagging feeling lurking right underneath, something akin to mourning. In an era when America increasingly relies on the Far East as a source of entertainment and inspiration, my private world, it seems, is private no longer. Asia exudes her mysticism and America is falling slowly under her spell.

Kung fu fighting, once exotic, has become the norm. At the beginning, learning martial arts was the foreground, the underlying plot of movies. Remember David Carradine, in Kung Fu in the early ’70s, who learned martial arts in China and then went on to search for his father in America? But these days kung fu fighting is so common that it serves as the background to various movies, television shows, video games, and ads. Turn on the TV and you’ll see ads like chatnow.com (where a young woman raises her foot menacingly near a man’s head while calmly talking to him) or cartoons like Kim Possible (where martial arts fighting seems like the normal activity of teenage girls) to children’s afternoon shows like the Power Rangers. There are also cult reruns of Xena: Warrior Princess (who can indeed paralyze someone with a touch of her finger!) or the ABC hit series Alias. Charlie’s Angels all know martial arts. In Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie employ their fighting skills to beat each other up as their marriage goes awry.

So much has changed since Bruce Lee first flew like an avenging god across the silver screen with his awe-inspiring kicks. Lee not only introduced martial arts to the West but also redefined cinematic action itself. Gone was the old idea that bigger is better. Swiftness and a precise kick can topple mass. Agility proves superior to brawn. The body in martial arts motion is pure art, a kind of acrobatic dance, endowed with a lethal elegance and grace that had not, up until Bruce Lee, been imagined cinematically.

The Hong Kong movie industry in the late ’80s and early ’90s took Bruce Lee’s legacy further when it experienced an all-too-brief renaissance. While it lagged behind the United States for a long time, Hong Kong, “The Hollywood of the East,” as it was called, suddenly made movies that, according to Li Cheuk-to, writing for Cinemaya, the Asian film quarterly, “not only astonished people, but more important, were unrestrained, free ranging and unburdened by tradition.” Jackie Chan becomes a globetrotting cop, and Michelle Yeoh can kick backward over her shoulder to dispose of an opponent, with each movie more inventive and fantastic than the last.

The decisive breakthrough in action movies came in the early 1990s, with movies such as Once Upon a Time in China, Swordsman II, and A Chinese Ghost Story, where characters are playful and barely affected by gravity. Dueling fighters float like birds in the air, wearing utterly fanciful costumes and following a story line even more fantastic than their accoutrement: a cult leader absorbs chi power from lesser fighters and shrinks them to nothing; energy bolts come through swords to split a horse in two; a fighter achieves super power but in the process must castrate himself and, in Hong Kong’s new gender-bending motif, turns into a beautiful woman.

Anything can happen in these movies, and the eye-blurring fighting reaches a level that is surreal and balletic. The new narrative seems to reflect a sense of uninhibited wildness, and the main characters—powerful eccentrics—often live outside the social norms, taking only what’s good of convention and discarding the rest. The movies examine and explore Confucian ideas, and along with them, issues of loyalty, patriotism, friendship, and love in modern ways. Hong Kong, like the rest of the globalized world, is moving into the age of options. Its kung fu movies become multiple-genre, and the story lines, along with the poetic choreography of its movies—not to mention cinematography—are often so stunning and clever that they leave an indelible mark on the rest of the world.

The Hong Kong film industry quickly spiraled downward when its stars and famous filmmakers left the ex-British colony as China took over. Rampant video piracy cut the industry’s dwindling profit margin to nearly nothing, while Bangkok and Seoul and mainland China turned into bona-fide new centers for filmmaking, even turning out fabulous martial arts movies. (Crouching Tiger was quickly followed by Hero, directed by Zhang Yimou, China’s best-known filmmaker. While cinematically arresting, Hero argued that an individual’s need for revenge is not as important as a country’s stability. It became a number one box-office smash in China.)

Hong Kong’s loss became Hollywood’s gain. John Woo, considered by many to be the best of Hong Kong filmmakers, moved to Hollywood in 1993 to make Hard Target, and then stayed. Woo rendered the likes of Tom Cruise, Jean-Claude Van Damme, and Nicolas Cage into slick action heroes. The mega hit, The Matrix, and its two subsequent sequels—a sci-fi series that married East and West, technology, and creation mythology—benefited greatly from a team of Hong Kong martial arts choreographers, chief among them Yuen Wo Ping, a martial arts master, who also shaped the careers of Jet Li and Jackie Chan. All the cinematic and martial arts skills that Hong Kong filmmakers had developed during the previous three decades were applied to render Keanu Reeves, the hapa (part-Asian, part-Caucasian) star—who played a neo-Christ/Buddha figure in a futuristic world ruled by machines—into a stunningly skilled martial artist.

Quentin Tarantino, who watched Hong Kong movies while working in a video store, made his breakthrough movie, Reservoir Dogs, by drawing heavily on Ringo Lam’s film City on Fire. Tarantino revolutionized Hollywood with his relentless pace and bloody but often humorous movies. Kill Bill Volume I and Kill Bill Volume II, for instance, are his tribute to the Shaw brothers’ kung fu movies. In them Uma Thurman plays a woman rising from a coma to take revenge on an assassin posse to which she once belonged. She wears a yellow jumpsuit, like Bruce Lee wore more than three decades before in Fist of Fury, as she hacks dozens of men to death. No one can oppose Thurman in her wrath.

The audience laughs when bodies are chopped and blood spurts in Kill Bill. Tarantino, like many directors these days, is reinventing the old genre, turning the slash-and-smash form into one with a traditional plot—finding a sharp sword, learning martial arts, seeking revenge—but that is also part homage and part satire, with a comic book aesthetic. The old kung fu movie has gone through dramatic changes, maturing to the point where it draws huge followings even while poking fun at itself.

(Tarantino is going further. He’s making an adventure film in China and in the ancient language of Mandarin. It makes sense. Hollywood has suffered of late with plummeting domestic sales, and increasingly sees Asia, especially China, with the largest middle-class population in the world, as its new market.)

But what does it mean when Tarantino, a white American, grows up to embrace China wholesale while Ang Lee, a Taiwanese, leaves Crouching Tiger behind to make Brokeback Mountain, a tearjerker gay-cowboy movie, based on a story by a straight white woman, Annie Proulx? Or when a nine-year-old black kid from Oakland named Tyler Thompson becomes an international opera star singing in Mandarin, while a refugee from Vietnam, Dat Nguyen, becomes a linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys, or the first “Vietnamese Cowboy,” as he is popularly called?

East and West—the twain has met, with the blessing of shared fascination. Tu Wei Ming, the Confucian scholar at Harvard, calls our new millennium “a second axial age.” “It is a kind of era where various traditions exist side by side for the first time for the picking,” he says. Traditions not only exist in our global village, they coexist in such a way “that a Christian project would have to be understood and perceived in a comparative religious context,” he notes.

But “moving from one civilization to another is a mutation, a metamorphosis that requires work and suffering,” warns Pascal Bruckner, a French novelist. Unlike in the movies, mastery of martial arts can only be achieved by years of practice and endurance. Mark Salzman, author of Iron and Silk, for instance, grew up watching kung fu movies. So enthralled with the marvels of China that he actually went there to learn martial arts and Mandarin, Salzman came back realizing that “when my teacher Pan did martial arts, he had total confidence, he was free. It was like seeing a bird fly. When I did it, it seemed put on, artificial.”

For years, on a wall in my study, I kept two very different pictures to remind me of the way East and West have changed. One is from a Time magazine issue on Buddhism in America. In it, a group of American Buddhists sit serenely in lotus position on a wooden veranda in Malibu overlooking a calm Pacific Ocean. The other is of a Vietnamese-American astronaut named Eugene Trinh, who made a flight on the space shuttle. The pictures tell me that East and West have not only met but also commingled and fused. We have come very far when Americans are turning inward, while a Vietnamese man who left his rice fields only a few decades ago thinks he can reach the moon.

A refugee to California, I once resigned myself to the idea that incense smoke, gongs, and Confucian dramas were simply an Asian immigrant’s preoccupation, a private affair of sorts. But I’ve changed my mind.

My own kung fu moment: I am at my writing desk, typing in the early morning, my oolong tea beside me. Cable cars rumble up and down the hills outside my window, their bells clanging merrily. But I’m not fully there. I’m in a land where cultures intersect and traditions crisscross, between swords flashing on ancient, lichen-covered temple rooftops and cars zooming down double-tiered freeways. Language is my weapon, invention my martial art—I seek to marry the New World to the Old Continent, fantasies to memories, and, through the act of writing, re-imagine the hemispheres as one.

Andrew Lam ’86 is an editor for Pacific News Service and a regular contributor for National Public Radio’s All Things Considered. Perfume Dreams, his book of essays on the Vietnamese diaspora, was published by Heyday Press in the fall.

From the January February 2006 Chinafornia issue of California.