Demand sensors

The big idea: “Most forms of energy, coming in and going out, are invisible to the eye. So it’s hard to get people to change their behavior because they don’t recognize how much they’re using,” says Pritesh Gandhi, founder of Ambient Devices. The Cambridge, Massachusetts, company makes a device called the Ambient Orb that sits stylishly on your desk or nightstand and changes color in sync with incoming data. The Orb was originally sold as a means to track the stock market, but a manager at Southern California Edison realized its potential as an energy conservation tool. He bought 120 of them and launched a small pilot program. The result? Customers using the Orb cut their peak-period energy use by 40 percent.

This experience tallies with what a group of students and professors at Berkeley believe is the next breakthrough in energy conservation—making it easier to do the right thing. “We don’t have to drastically change our lifestyle, not yet anyway, but we do have to drastically change the way we use our resources,” says Ron Hofmann, senior advisor at UC’s California Institute for Energy and the Environment. “And how we’re going to do that is by getting information about energy usage into the hands of consumers.”

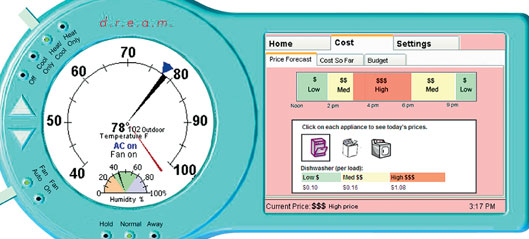

Among other things, Hofmann and his colleagues are working on sensors that will measure and display how much energy is used by each appliance in your home, and then aggregate the information so you can understand your total “power draw” at any given time. “As it stands, even if you get an electric bill that’s higher than you expected, it’s been weeks since that energy was used and you have little idea what you can do to get it down,” explains Hoffman’s Berkeley colleague Paul Wright. But if every appliance in your home were outfitted with a “smart plug” or “smart cable,” you would. “That information can be sent to your PC, your cell phone, or wherever you wanted it sent—you could see and do something about it in real time,” he says.

What’s next: There are still issues in getting the utilities to display the information and price the energy in a way that will create an incentive for conservation. But Wright believes that we’re likely “only one or two years away from being able to buy these things.”