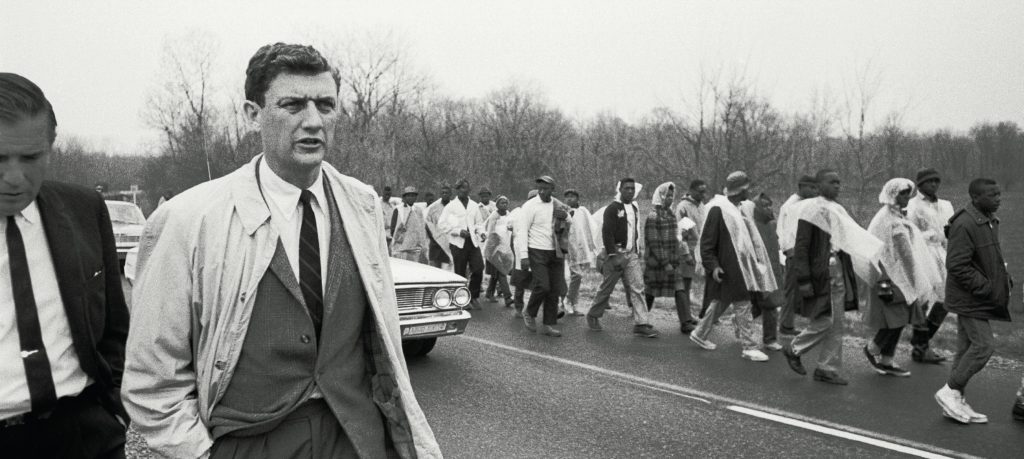

Thelton Eugene Henderson didn’t study the civil rights movement; he lived it. After earning his law degree from UC Berkeley in 1962, he joined the Justice Department as the first African-American lawyer in its civil rights division. Working with his mentor and fellow Cal grad, John Doar, Henderson traveled often to the South to monitor law enforcement on civil rights cases. He investigated the famous case of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four young girls.

And he also experienced firsthand the South’s fierce racist opposition to civil rights for blacks.

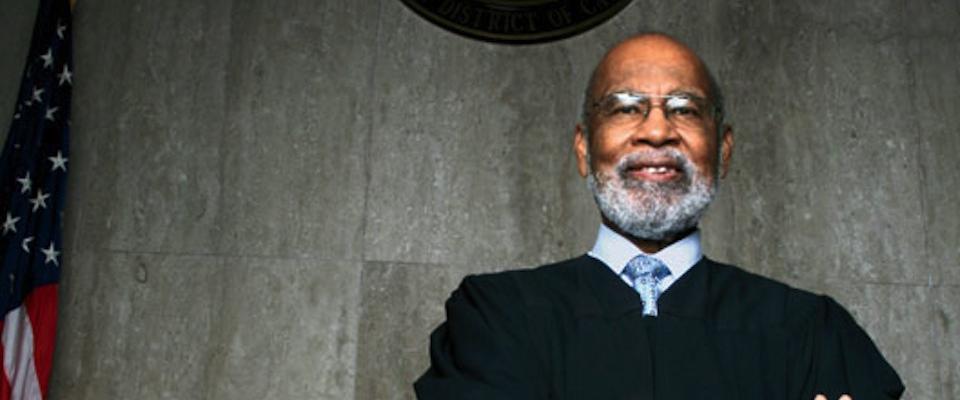

Henderson, who would go on to be named the Cal Alumni Association’s 2008 Alumnus of the Year, has spent decades as federal judge in the Northern District of California. His rulings have affected numerous controversial, high-profile cases: on behalf of prisoners’ rights to humane treatment, on behalf of dolphins threatened by tuna nets, on behalf of Vietnam veterans exposed to Agent Orange, on behalf of gays subjected to added security scrutiny in the tech industry, on behalf of women in a landmark discrimination suit against State Farm Insurance, and in oversight efforts to resolve tensions between Oakland Police and its citizenry.

Born in Shreveport, Louisiana, in 1933, Henderson was raised in Los Angeles. The star football and baseball player was recruited by UC Berkeley, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in political science in 1955. In 1962 Henderson received a law degree from Boalt Hall and joined the Justice Department as the first African-American lawyer in its civil rights division. Working

Returning to the Bay Area, he became director of the Legal Aid Society in East Palo Alto. That position brought him to the attention of Stanford Law School, where he was hired as assistant dean and established a minority recruitment program. He left Stanford in 1977 to establish a law firm specializing in civil rights, and also taught at Golden Gate University.

In 2001–02, Leah McGarrigle of The Bancroft Library’s Regional Oral History Office conducted extensive interviews with Judge Henderson (available on ROHO’s website). What follows is an introduction by Henderson’s friend, Berkeley sociologist Troy Duster, then excerpts from the oral history.

In his story, one will read about how his loan of a Justice Department rental car to Martin Luther King became a significant political happening.

When our paths first crossed as very young men, both near the beginning of our careers, I was struck then, as I am now nearly four decades later, at how political events of some magnitude just seemed to happen around Thelton. In his story, one will read about how his loan of a Justice Department rental car to Martin Luther King became a significant political happening. Now, nearly halfway through the first decade of the new century, there is the story of how Thelton’s “routine” stewardship of a California prison would bring him in to a dramatically public collision with Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. And in between, there have been scores of similar tales of seeming happenstance that were converted into events of political magnitude.

If you just heard Thelton tell the story over coffee, you would conclude that—there he was, minding his own business, or just doing the commonly decent thing. Suddenly, he would say, things got blown out of proportion, and his actions inexplicably become the subject of a New York Times editorial. While it is undeniably true that extraordinary things happen to ordinary people, it is also true that extraordinary people seem to convert “ordinary happenings” into events of significant moment. So how much of this is the person, and how much of it is the times? The answer lies in the relationship between two.

In the early 1970s Thelton was on the law faculty at Stanford, when I was on the Berkeley faculty of Letters and Science. Each was one of the only African Americans in the professoriate at our respective institutions, and we have always compared notes about that particular aspect of the social worlds that we inhabit. It was not uncommon for students to knock on his door, walk in, and ask “Is Professor Henderson here?” The same happened to me, and in our own choreographed way, we would compete with one another as to who could come up with the best and swiftest comeback. Thelton won, hands down. One day, after he had become an assistant dean at the law school in Stanford, a newly arrived student successfully made it past the inner screening of an administrative assistant, who said, “You may see the dean now.” The student walked into the vast inner office, saw Thelton alone at his desk, paused, and asked, “Is Dean Henderson here?” Thelton peered slowly at him over his glasses, and told the student to have a seat, and said matter-of-factly, “Dean Henderson will be with you shortly.” Thelton returned to his work, completed another five minutes of what he was doing, then looked up and said, “Dean Henderson is here now.” In this little vignette, one can discern the interlacing of wit and humor with a latent but fierce tone of serious purpose. It was an “ordinary moment” in some ways, but that moment surely seared itself into the student’s experience. Extraordinary people can make ordinary moments memorable.

At a personal level, Thelton is easygoing, affable, flexible, congenial, and possessed of a laugh that is so infectious and so deeply resonant that those within range find themselves smiling. To this add a mischievous teasing style, somewhat in the tradition of Shakespeare’s version of Falstaff. Even when Falstaff was seemingly bested by his peers in some sparring verbal one-upsmanship, he was always able to find his way back on top with a cleverly humorous turn of a phrase or frame. The affability and flexibility are real, wide-ranging, even characterological. But when he has extended himself, and an attorney in his courtroom crosses a line, the fiercely uncompromising part emerges, a stony steel-like resolve catches many a foe off guard and can become a newsworthy event.

It is the quiet determination that is most notable. Because he is so willing to let others take the stage and dominate a conversation, a dinner party, or a seminar, those who meet Thelton for the first time are often surprised at the clarity and strength of his convictions when he finally gives voice to them. In [his] history, the reader will find a healthy counter-balance to the media portrayal of Thelton Henderson as controversial. It will become clear that it was not that Thelton chose to do battle. Rather, it is almost always the case that Thelton chose to do the right thing, remained steadfast and unwavering, and the battle was joined by those who objected.

—Troy Duster

The way I got my name, my mother was in the hospital waiting to give birth. I was scheduled to be Eugene, named after my father, Eugene or Gene, Junior. Somewhere in the process the nurse, who was a white nurse and that’s relevant to this story, said something to the effect, “Gee, I think Thelton is a pretty name.” And my mother, as she tells it, in those days certainly, they got shots or some sorts of medication to help the process and she was sort of in that state and said, “Oh, gee, Thelton is pretty” and named me Thelton on the spot.

We came [to California] with all the worldly possessions. I like to refer to it as Joad-style, like the Joads in The Grapes of Wrath…. We came by truck and settled in on—first house we lived in was on 53rd Street. Everyone lived there.

Mike Marionthall … was a tough ex-marine who was an All-American guard at UCLA, lost his leg in the war. Came back, got out, wooden leg. Not wooden, but a prosthetic, I guess you would call it. And came to teach and coach at Jefferson High, an all-black school with a bunch of tough kids. Discipline problems. And past coaches, they just got overwhelmed by it…. Mike wasn’t that kind of guy. I think, having been wounded in the war, he had a different view and he wasn’t taking any of that crap. And he shaped us up. Some of the tough guys on the team that were trying to do numbers on him, he’d say, “Sit your butt down.” And nobody took him on. So, we had a great football team just when I came along. And that helped me get my scholarship to Cal. I think that made all the difference in the world…. All I knew about Cal was that they had a good football team in those days…. I had not the foggiest idea that it was an excellent academic institution.

Berkeley, you know, is known as the liberal bastion now, but it wasn’t that liberal then, in terms of housing…. Even in subsequent years, when I played baseball—became really good friends with one of the white baseball players and we were going to be roommates. We went around looking for places, and they wouldn’t rent to us. We ended up not being roommates…I think that the athletic department found this owner that would accept blacks and that’s where we all went.

Henderson joined the Army in 1956 and returned to Berkeley, which “wasn’t the same place.”

Don Warden was a remarkable guy. He had been a child evangelist and had traveled around the world and met Gandhi when he was a kid … he started something called the Afro American Association, AAA. He had a house over in Oakland, right across the border, that he bought and lived in. He would have meetings there. It was the blacks on campus primarily, but it expanded to blacks who weren’t in school. We would meet at his house on Sunday and we would read a book on the black experience, whatever it might be, something by Richard Wright. It was, I remember, the first time I ever really learned about Marcus Garvey and many of our black heroes and black prominent people….

It’s interesting the people that were involved in it. Ron Dellums who went on to be a congressman. A number of people, Huey Newton and Bobby Seal—they were young then, they were young kids—if the Panthers was even a part of their imagination, or whether it may have even started forming in those meetings.

“Now that I’ve been a federal judge for a number of years, I look back on it and I am shocked—and yet, not surprised.”

After obtaining his law degree, Henderson joined the Justice Department.

I just didn’t know that in the nation’s capital we would have these seventeen lawyers that were really dedicated—we just—that’s all we did—we were going to win the civil rights battle by ourselves, work long hours, and it was almost a competition to see who could work the latest. Sometimes we would work up until seven and, “Well, let’s go to dinner.” They had been doing this, the older guys, for years, and all of a sudden they would say, “Oh, we can’t go to that place, because we can’t take Thelton.” That was a surprise. That was a shock to me because even with the housing discrimination in Berkeley, I had never experienced that….

As a young lawyer right out of law school, I don’t think I had a broad perspective about the Southern judges that we were appearing before. Now that I’ve been a federal judge for a number of years, I look back on it and I am shocked—and yet, not surprised. I mean, the Southern judges that we appeared before on the voting rights cases and civil rights cases were out-and-out racists. They didn’t disguise it in court, and they certainly didn’t disguise it when a black like myself appeared in front of them…. They did not follow the law, they did not follow the rules. They did not apply the facts that they were given for a fair result. They were there to achieve a purpose, which was to preserve the Jim Crow laws and segregation….

The great saving grace of it all was the judges on the Fifth Circuit, who did follow the rules, even though they were Southerners … they upheld the law, and I think they saved the day for everyone there by giving some credibility to a system, a legal system in the South.

In 1980, Senator Alan Cranston was considering various candidates for the federal district court.

I got a call that said we would like you to meet with Senator Cranston at his office at Halliday Plaza at four o’clock today…. I thought the only thing that could bother him would be this lending of the car to Martin Luther King. So I called John Doar and I said, “Gee, I’ve got this meeting and I’m worried.” … I said, would you please call Alan Cranston about this, and put it in perspective and explain it. He said he would. So I sweated the whole day…. They asked me about the car, among other things, and I told them what happened. Then [Cranston] said—the first time I got an indication that maybe things were going to go OK—he said, “Well, we got a call from John Doar today,” and something to the effect, “I would trust that man with my life,” in terms of his integrity. “And he said that I needed to understand the times there, and if I deprived you of a judgeship because of that, I would never forgive myself.” And I thought, OK, that has to be helpful. So we went on a bit, and then finally he said, “OK, well, I’m satisfied, you’re going to be our next federal judge.”

In 1996, Henderson drew fire when he ruled California Proposition 209 unconstitutional.

I was very naive about the emotional impact of affirmative action. I knew it was an issue in our society, I had no concept that this was such an emotional issue until this decision…. I knew it was going to be controversial, I had no question about that, but I thought it would take the same course as anything else I did that was controversial. We talked about some of these, you know, the clean air thing [when he ruled in favor of Sierra Club in a high-profile case]. I relied upon—I’ve forgotten now—a 1982 Supreme Court case, which has never been reversed, that essentially said that a referendum created an unconstitutional hurdle for minorities. I analogized that and I thought that Prop. 209 created an extra hurdle for minorities in the area of affirmative action, and I found that that was unconstitutional. You can differ with that analysis, but I thought it was a legitimate analysis of the law.

Henderson was asked for his advice to the young.

I hoped that my son would see the end of discrimination, and am now hoping that my grandson will see it and realizing that he won’t, and hoping that at some point in his line of children, it would end. I’m not yet cynical because I still have the hope that things will be better—well, indeed, things are better, but that they will progress faster than they have.