Legendary historian Leon Litwack says goodbye.

In 43 years as a Berkeley professor, retiring historian Leon Litwack ’51, Ph.D. ’58, taught more than 30,000 students. An impressive fraction returned to Wheeler Auditorium on a hot day in early May to hear their teacher deliver the final lecture for History 7B, his signature survey of post–Civil War American history. Students who failed to arrive early—and instead showed up merely on time—found no place to sit, except the aisles.

“I came from New York City for this lecture. I wouldn’t miss it,” said Steve Brier ’67, an historian and vice president of the City University of New York Graduate Center. “The passion about studying the past and trying to understand what happened to people who otherwise were invisible—that I learned from Leon. He was an inspiration.”

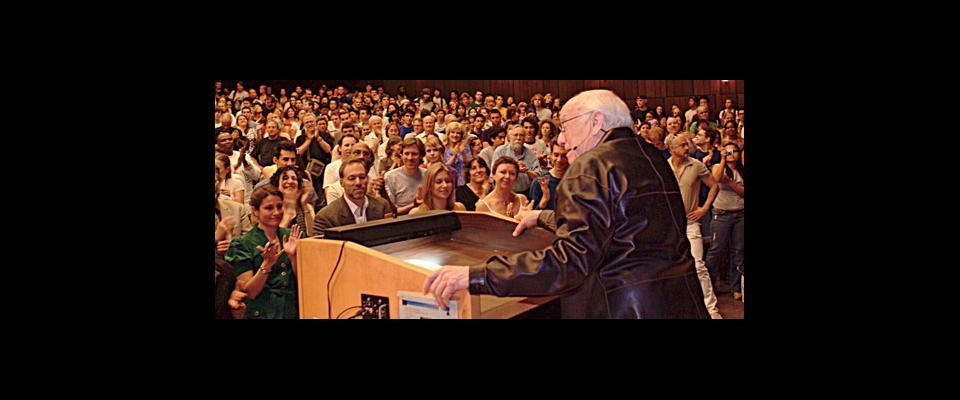

As Litwack, 77, walked on stage, the pre-lecture conversational rumble erupted into a standing ovation. Freshmen dressed for the 90-degree heat in flip-flops and spaghetti straps cheered as loudly as their older counterparts with collared shirts and salt-and-pepper hair. Digital cameras emerged from pockets to capture the moment. Litwack waved off the applause, the crowd settled, and he began, in his gravelly baritone, to speak. Leaning on the lectern, dressed nattily in his hallmark leather jacket, Litwack quoted sharecroppers, civil rights activists, and hip-hop artists to spin an unsettling argument about the fate of the civil rights movement. “Everything’s changed,” he said of an America that watched poor blacks suffer disproportionately in the flooding after Hurricane Katrina, “and nothing has changed.”

The Litwack legend is based, in large part, on lectures like these: 50-minute crafted orations, peppered with primary sources, humor, and stories meant to make students rethink the self-congratulatory, nostalgic version of American history most often taught in schools. There is no PowerPoint in a Litwack lecture—just the old-fashioned power of his carefully chosen words and his earnest push for equity. He provides arresting examples of injustice and racism in a land of the ostensibly free. “I have one chance at them,” Litwack said of his students, predominantly freshmen and sophomores, in a 2001 interview with Roy Rosenzweig of History Matters. “One opportunity to engage them in the study of the past, to force them to see and to feel the past in ways that may be genuinely disturbing.”

As a high school student, Litwack read W.E.B. DuBois’s Black Reconstruction in America, then stood up in class to challenge his history textbook’s depiction of black slaves as docile and contented. By the time he came to Berkeley in 1948 as an undergraduate, he was already fascinated with the disparities between America’s social, economic, and racial inequalities and its professed ideals. His commitment to illuminating that contradiction made him a hero to Berkeley’s left-leaning students. “He embodies every positive attribute of UC Berkeley as an institution that embraces independent thought and conviction and standing up for what you believe in,” said Amy Lippert, head graduate student instructor for History 7B. “He’s a California institution.” Litwack’s former students, many teachers themselves, continue to be inspired by his passion, and continue to spread his message. “History’s not always pretty. It’s not always nice,” said Mary Alba ’02, a seventh grade teacher in Los Angeles. “I teach history the way he taught it to me. And yes, I’ve gotten in trouble. Yes, I’ve been suspended without pay. Because of him, I don’t back down.”

For his dedication in the classroom, Litwack has earned a Distinguished Teaching Award and the Golden Apple, an honor students confer upon their favorite professor. His scholarship has earned a Guggenheim fellowship and a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, among other awards. “He deserves a great deal of credit for making the general public, as well as the historical profession, aware of the richness of African American achievements in American life, and aware, also, of the depth and intensity of anti-black racism,” said history department chair David Hollinger. “It is partly because of Litwack that many school children today learn of the severity of anti-black racism in American history.”

Litwack won a 1980 Pulitzer Prize and the 1981 National Book Award for his account of the South after emancipation, Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery. Two decades later, he wrote a sequel, Trouble in Mind, which acclaimed Yale historian C. Vann Woodward called “the most complete and moving account we have had of what the victims of the Jim Crow South suffered and somehow endured.”

At the end of his last lecture, Litwack paused. The auditorium was warm and airless. Students put down their pens, and everyone in the audience seemed to lean forward, the better to hear his reflections, which he had—characteristically— prepared in advance. “There’s an old folk saying,” he said, “‘Life’s a dream; please don’t wake me up.’ That’s how I feel about my life, my years at Berkeley. When I hear UC Berkeley denounced for lawlessness, debauchery, free thinking, subversion, harboring communists and radicals, exposing students to radical ideas— whenever I hear those charges made, that’s when you’ll hear me, wherever I am, shout: Go Bears!” Eight hundred people rose from their chairs to offer thanks. Digital cameras re-emerged from pockets. The applause lasted a full four minutes before Litwack turned to leave the stage.

“You know, people talk about going to a university: Broaden your mind, open doors, get the bigger perspective. He epitomizes that,” said Valerie Cheasty ’73, whose son Justin was a freshman in Litwack’s class this past year. “He was the university, for me.”