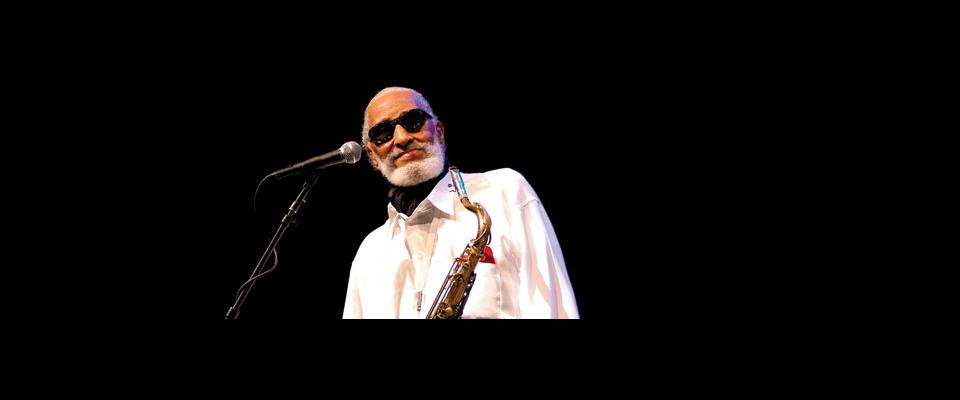

Jazz legend Sonny Rollins is still improvising—brilliantly.

Often hailed as the last jazz immortal, 77-year-old tenor sax legend Sonny Rollins has helped shape the course of American culture for more than half a century with his brawny tone, gift for thematic improvisation, and uncanny skill at exploiting rhythmic freedom. Beyond his pervasive influence as a player, composer, and bandleader, Rollins exemplifies the jazz musician as moral force, often taking forceful but unideological stances on human rights and environmental issues.

He returns to Zellerbach Hall for a Cal Performances concert on Thursday, April 3, with a pianoless band including longtime bassist Bob Cranshaw, trombonist Clifton Anderson, and guitarist Bobby Broom.

Even before he started recording as a teenager in the late 1940s with bebop pioneers such as trombonist J.J. Johnson and pianist Bud Powell, the Harlem-raised Rollins displayed a presence beyond his years. “When I was a youngster, around 12 or 13, we had a little softball club, and the guys made me the president,” Rollins says, still sounding a little mystified by the respect he effortlessly engendered. “I wasn’t the oldest guy in the group, but they made me the president of the club, so it may be something in my constitution or my bearing,” Rollins continues, speaking by phone from his home in the Hudson River Valley. “I certainly don’t enjoy telling people what to do, so it’s sort of funny when you think about it. I’m a bandleader like Miles Davis, I don’t like telling people anything. If they’re playing with me they should know what to do.”

There’s nothing mysterious about Rollins’s impact as a player. Possessed of one of the most glorious sounds in jazz, he is a volcanic improviser capable of reeling off ten-minute solos that build thematically while generating extraordinary momentum. Rollins’s penchant for West Indian rhythms gives his music an infectious buoyancy that works in counterpoint to the muscular weight of his tone.

Along with Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and John Coltrane, Rollins defined the tenor sax as the dominant horn in the jazz canon. He’s composed more than a half-dozen jazz standards, including “Oleo,” “Doxy,” “Sonnymoon for Two,” “Tenor Madness,” and the calypso anthem “St. Thomas.” But he also has a knack for turning the unlikeliest tunes into effective jazz vehicles. Rollins kicks off his first LP, the 1955 Prestige album Worktime, with a harrowing version of “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” And on his Riverside debut, 1957’s The Sound of Sonny, he tears through “Toot, Toot, Tootsie,” a tune indelibly associated with Al Jolson.

To this day, just about any Rollins performance is likely to include a Tin Pan Alley tune from left field. According to guitarist Broom, Rollins has been exploring Noel Coward’s “Someday I’ll Find You,” a piece he first recorded on his seminal 1958 Civil Rights statement, Freedom Suite.

“I get a kick out of watching Sonny and Bob Cranshaw,” Broom says. “They just go back to their youth, drawing on their memories of all these tunes. But Sonny can find material anywhere. During my first stint with him, he did the Dolly Parton hit ‘Here You Come Again.’ Nobody would touch that! The thing about these songs, there’s everything right with them. It’s got a form that’s akin to a standard. It’s got a good melody and jazz standard–type chord changes. But do you have the cojones to take on a tune where somebody might look at you and say, ‘What are you doing?!'”

Since he came into his own in the mid-1950s, Rollins has exerted an inexorable pull on his fellow improvisers, influencing several generations of players. Berkeley-raised tenor sax star Joshua Redman, whose latest album, Back East, was consciously designed as a response to Rollins’s 1957 classic, Way Out West, speaks for countless musicians (and not only saxophonists) when he describes the impact of hearing Rollins’s albums.

“It wasn’t until I heard his records that I think I really became aware of the true power and potential of jazz improvisation,” Redman says. “[Rollins] was the first improviser who made me aware of the potential balance that can be struck between complete spontaneity and always telling a story, always having a logic and an organic unity to an improvisation. Sonny Rollins could be completely in the moment and completely structured at the same time, and that really changed the way I thought about improvisation.”

Born Theodore Walter Rollins, he was raised in Harlem in the 1930s, a time and place where kids dreamed of becoming musicians. His neighborhood brimmed with musical talent—childhood friends included future jazz luminaries such as alto saxophonist Jackie McLean, drummer Art Taylor, and pianist Kenny Drew—but Rollins quickly developed a reputation as the most formidable young musician on the scene. After starting piano lessons at age 9, he moved to alto sax two years later. In his midteens, Rollins made the switch to the larger horn, inspired by the man who virtually invented the tenor as a jazz instrument.

“Coleman Hawkins was my idol, and I wanted to play like him,” Rollins recalls. “I wanted to incorporate his sound, so I began using a tenor reed on my alto. That’s why I really wanted to switch. When my mother was able to afford one, she got me a tenor.”

During the first half of the ’50s, he recorded as a side man with the leading figures in modern jazz, including trumpeters Miles Davis and Fats Navarro and pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk. Rollins’s career really took off when he joined the Max Roach/Clifford Brown Quintet in 1955, a band rivaled only by the Miles Davis Quintet as the top modern-jazz combo of the day. But it was his own recordings from 1956 to 1959, such as Saxophone Colossus, Way Out West, and A Night at the Village Vanguard, that made him the most revered and influential tenor saxophonist of the decade.

Indeed, the adulation became so overwhelming that at the end of the decade Rollins took the first of what he calls his “sabbaticals,” withdrawing from the music business. But his legend only increased, as reports circulated that he was spending endless hours practicing on the Williamsburg Bridge.

“The people were getting very enthusiastic, and I had a pretty big jazz name after making all those records,” Rollins says. “Being basically self-taught, I always felt not quite finished as a musician. I had something to live up to and felt I needed some more ammunition, so I went back in the woodshed, only in this case it was on the Bridge.”

When he returned to the scene in 1962 with the aptly named The Bridge, Rollins had incorporated the rhythmic and harmonic freedom introduced in his absence by Ornette Coleman, while also drawing increasingly on the calypso beats to which he was first exposed by his Caribbean-born mother. It’s an approach that he’s still refining.

“Instead of getting more technical I wanted to go in the other direction and get more aboriginal, if you will,” Rollins says. “There are possibilities in there. I’m hearing in the distance something that I haven’t done yet.”