San Francisco based Linden Lab set out to build virtual reality hardware; instead the company ended up creating an entire virtual world. Freed from the laws of physics and suburban propriety, in Second Life your house can float, your neighbors might be elves, and you are welcome to go about your business as a giant bug or a bikini-wearing hottie. The online society went from colony to megalopolis with remarkable speed. Launched in 2003, Second Life now boasts millions of registered users, as many as 58,000 of whom are online at any one time.

The population boom is in part due to a remarkably robust economic engine: In an ingenious twist, the company not only gets its players to create game content for free, it also charges them to be there. (Basic membership is free, but serious players pay monthly fees for “land” upon which they can erect businesses or build elaborate, albeit virtual, homes.) By giving players intellectual property rights to whatever they create, Linden Lab encourages them to design new game objects—anything from clothing to home décor to code governing the way avatars move—which can be sold to their fellow players using the local currency, the Linden Dollar. The coin of the virtual realm, Linden Dollars can be exchanged for actual greenbacks, and transactions worth around $1.5 million in U.S. dollars happen every day in Second Life.

A reported 40,000 users are actually profiting from game play; Second Life has generated its own real estate titans, fashion designers, and even software developers who have created games-within-the-game that were ultimately licensed by companies in well, real life.

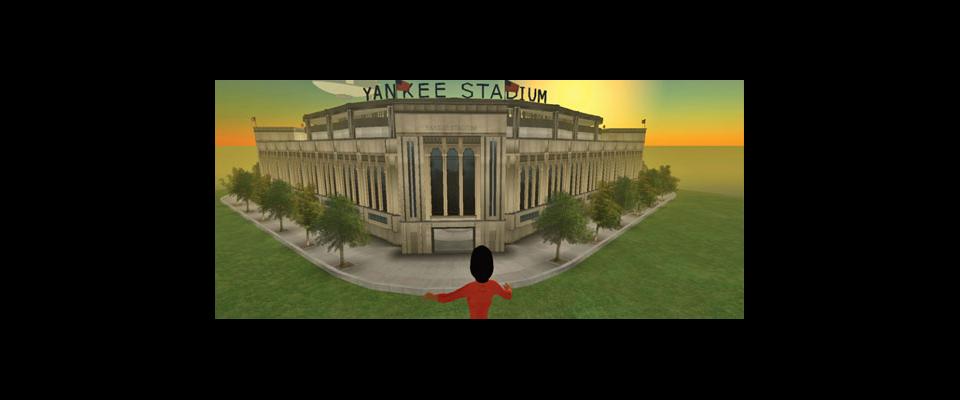

Over the past two years, some big names have moved into town. Companies such as IBM, Dell, Adidas, and Toyota promote their products in the virtual space, or use it to conduct business meetings or training sessions. Second Life has spawned online newspapers like the Second Life Herald www.secondlifeherald.com, but it also serves as an outpost for the real world’s Reuters news service. Universities offer online classes in Second Life; musicians like Jay-Z and Suzanne Vega have given streaming audio concerts to virtual fans; and if you tune in during a broadcast of National Public Radio’s Science Friday, your avatar can pose questions to be answered on-air by host Ira Flatow.

Lately, though, the boomtown days have bumped up against real-world limitations. Both gambling and banking have been banned from Second Life, the former due to worries about the legality of virtual gaming, and the latter after an in-game bank collapsed, taking investors’ money with it. And although Linden Lab purposefully created a laissez-faire society, land disputes and fraud claims have now raised nagging concerns about how to police players. On the technical side, as population grew, server demand increased, resulting in glitches and lag time.

Under-population may actually be a bigger problem. Second Life has no built-in objective, and many newbies complain of not knowing what to do once they’re there. Attrition is high. About 85 percent of users drop out within two months of registering. Last summer, Wired magazine ran an article unambiguously titled “How Madison Avenue Is Wasting Millions on a Deserted Second Life,” which told of bummed-out execs from Coca-Cola and the NBA who claimed that their Second Life traffic was moribund.

This is a critical issue. Since Second Life is essentially a social networking site with a 3-D interface, its success or failure will hinge on its ability to retain an active, creative population. Linden Lab’s plan for the next stage of development is to make the Second Life environment more livable by improving graphics rendering and platform stability while making it easier for users to search for people and places of interest. The company is also encouraging the development of new applications that would make the site more media platform than game, while collaborating with IBM to develop ways for Second Life avatars to venture into other virtual worlds. Linden Lab CEO Philip Rosedale, who describes Second Life as a 3-D Internet browser, is betting that virtual reality will become nearly ubiquitous one day—as prevalent as cell phones and email are today. For now, it’s clear that if Second Life hopes to be part of that reality, it will need to get its second wind.