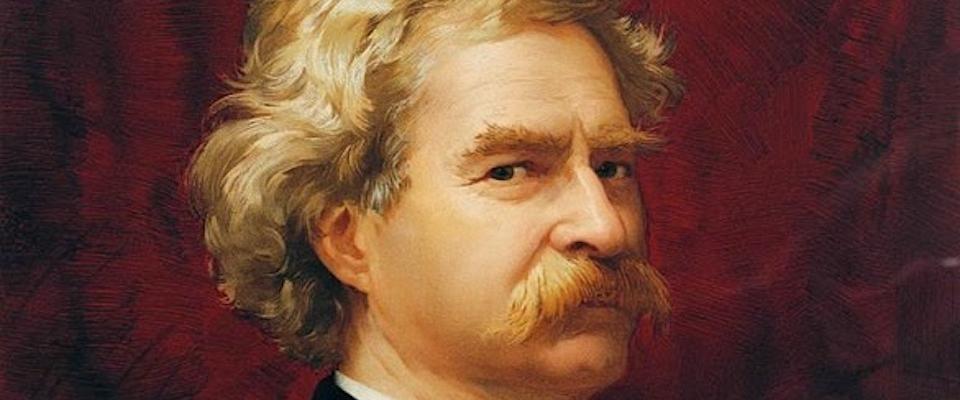

Introducing the curious autobiography of Mark Twain

Samuel Clemens—better known as Mark Twain—dictated the passages that follow in the summer of 1906, in a house he was renting in New Hampshire. For some 30 years, off and on, America’s greatest humorist had dabbled at writing his autobiography, putting scraps of it down on paper here and there, but never bringing anything to publication. Now, at 71, he had begun again in earnest, not writing the thing but telling it, in daily monologs. In the mornings, he dictated long reminiscences to a stenographer, who took it all down in shorthand then delivered typescripts for him to review in the afternoons. These Clemens would correct, being careful not to edit out “the subtle something” that he felt made “good talk so much better than the best imitation of it that can be done with a pen.”

The method was intentional. More than anything, Clemens wanted to produce a “true” book, and dictation, he felt, was a way to keep the inner censor at bay. At the same time, he worried that the truth would cause offense, and it was his express desire that the bulk of the autobiography be published long after he and his immediate heirs had passed away. Clemens believed free speech to be “the privilege of the dead.” Publishing his memoirs posthumously would afford him that privilege.

And yet, for all his talk of truth-telling, Clemens failed to reveal much of himself. His official biographer, Albert Bigelow Paine, lamented that the dictations bore only “an atmospheric relation to history.” And Clemens’s friend and editor William Dean Howells chided him for being “dramatic and unconscious” and for lacking introspection. “You count the thing more than yourself,” Howells wrote. The old author defended the effort, insisting that, “the remorseless truth is there, between the lines, where the author-cat is raking dust upon it which hides from the disinterested spectator neither it nor its smell.”

Whether or not the modern reader is able to catch a whiff of the real Clemens in the resulting pages, the autobiography is both refreshing and strange—not literature really, but something no less remarkable. Justin Kaplan, author of the Pulitzer-winning study, Mr. Clemens and Mark Twain, proclaimed it “a sprawling and shapeless masterpiece” and “a record of magnificent talk.”

Clemens kept up the dictations until the summer of 1908. By then, the output approached half a million words. Versions of, and selections from, the autobiography have appeared over the years, but the comprehensive edition is not due out until 2010, a century after his death, when UC Press and the Mark Twain Project will produce the definitive autobiography in three volumes. The passages on Hell or San Francisco and on The Prince and the President have never been published before.

Ladies and gentlemen, it is an honor to present to you Mr. Mark Twain.

Read