“It’s a sort of will-o-the-wisp thing,” Glenn Seaborg once said of the discovery of plutonium. “We saw it and then it disappeared. Then we saw it again and then it disappeared and then finally we saw it and we could confirm it.” That confirmation happened in Room 307 Gilman Hall, on February 23, 1941. It was a stormy night, Seaborg recalled. The 5 microgram sample of “element 94” had been bombarded in Ernest O. Lawrence’s 60-inch cyclotron. On May 29, 1941, Seaborg and his team filed a report of their results to Washington; by spring the following year, he had left for the Manhattan Project, and it was not until after WWII that the discovery was announced publicly. The room has since been declared a National Historic Landmark, and in the naming ceremony Seaborg returned to comment it had changed little in the 25 years since he’d worked there. Now in the care of chemical engineering professor John Newman, the room, with its equipment too antiquated for modern experiments, lies little used. Seaborg bequeathed the original sample of plutonium, housed in the old cigar box where he’d kept it, to the Smithsonian Museum.

307 Gilman

Related Articles

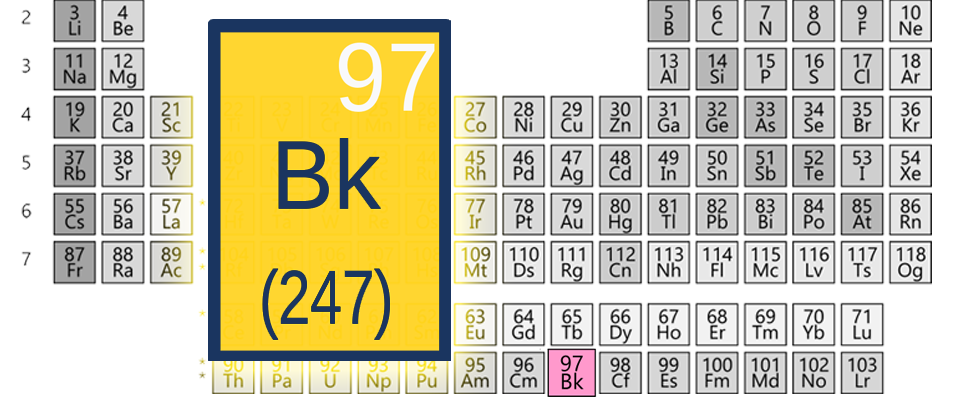

The Element Named After Berkeley

Hint: It’s not stanfordium, oxfordium, or caltechium. Glenn Seaborg was born too late to have spawned Cal’s spirit cry. It’s coincidence, surely, that his name is an anagram for “Go Bears!” And, although he was definitely a Bears fan and was Chancellor when Cal last made it to the Rose Bowl in 1959, he was […]

Branding the Elements: Berkeley Stakes its Claims on the Periodic Table

Let the other universities brand themselves with the presidents they’ve produced, the corporations they’ve midwifed, their location in a small town outside of Boston, or their number one football team. At Berkeley, we’re OK with being number 97. On the periodic table of elements. You may have heard of “the table,” as we call it […]

A Noble Company

A history of celebrating Cal. The Cal Alumni Association came full circle with this year’s Charter Gala, celebrating Cal’s 144th anniversary and CAA’s 140th. The event on March 24 returned to the San Francisco Palace Hotel after a long absence. And once again, Howard “Howdy” Brownson ’48 led everyone in “Hail to California,” just as he […]