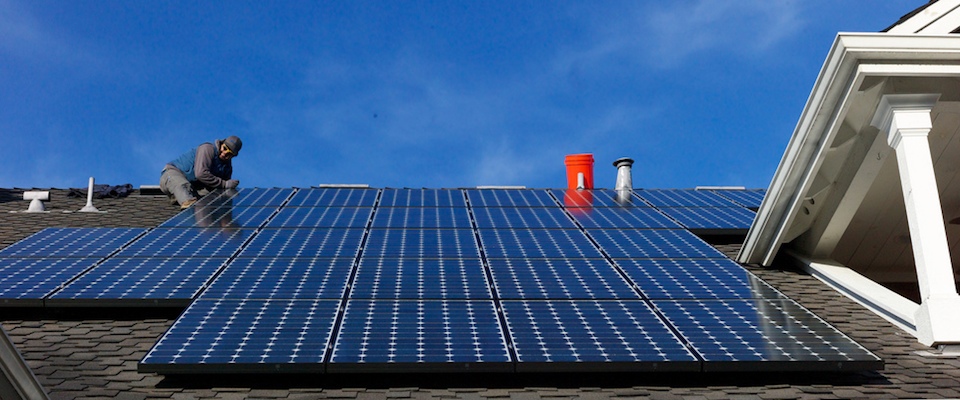

Earlier this month, California became the first state to require all new homes to have solar power. The mandate, which comes from the California Energy Commission (CEC), will take effect in 2020, making solar power even more common in a state that already boasts about half the country’s solar generating capacity. Part of the motivation for the new policy is California’s ambitious goal to be producing 50% of the state’s energy from renewable sources by 2030.

If a policy that lowers reliance on fossil fuels sounds like a win, especially under an administration that refuses to acknowledge climate change, the controversy surrounding this move, even among alternative energy advocates, is surprising. Energy economists in particular argue that a rooftop solar mandate is an expensive and inefficient way to address climate change. On the morning of their vote, UC Berkeley Haas School of Business professor Severin Borenstein emailed the CEC to urge them not to approve the mandate. Here are seven things you should know about the policy, and why experts are arguing about it:

1. The solar mandate doesn’t require all new homes to have solar panels.

New homes can either get their electricity from rooftop panels or from a shared solar grid that serves multiple homes. Even among rooftop solar panel options, there’s some flexibility. Solar arrays can either be purchased outright or leased, and must be a minimum of 2 to 3 kilowatts (according to the New York Times, most home solar arrays are two to three times that size).

2. Solar panels will make new homes more expensive but should result in savings over time.

The CEC estimates that its new standards (which include the solar mandate as well as other building efficiency rules related to issues like insulation and ventilation) add $9,500 to the cost of a new home but save $19,000 on electricity over 30 years. In an analysis in Vox, David Roberts wrote that the commission probably overestimated costs (because the price of solar panels is already falling, and panels for new developments will likely be bought in bulk), meaning savings for solar customers will likely be even higher. Most solar panels come with a 25- to 30-year warranty, and while they will be less efficient at that age, they can still produce electricity. Plus, as technology improves, so does solar panel longevity.

When you pay your utility for electricity, a significant portion of your bill goes toward grid maintenance. The more people who opt out in favor of solar, the more that cost shifts to the remaining utility customers.

3. Solar panels won’t fill all your energy needs, unless you have a battery.

Even when you have rooftop solar panels, you’ll most likely still rely on the grid for some of your electricity. The power your panels produce has to be used or stored in a battery immediately, and any excess goes to the grid where it can serve other buildings in your area. Batteries aren’t just useful for nighttime energy needs; they also provide extra protection against power outages caused by earthquakes or other natural disasters. Still, batteries can be expensive, typically costing $5,000 or more.

And because of a program called “net metering,” solar customers haven’t had much incentive to buy batteries. If you qualify for net metering (which you can apply for through your utility), you’ll receive credits for the power you provide, which you can use to buy power from the grid during the non-solar producing hours of the day.

4. Going solar makes the grid more expensive for everyone else.

This is a major part of the argument against the solar mandate. When you pay your utility for electricity, a significant portion of your bill goes toward grid maintenance. The more people who opt out in favor of solar, the more that cost shifts to the remaining utility customers. Lucas Davis, another Haas professor, wrote a post about this on the Energy Institute blog, titled “Why Am I Paying $65/year for Your Solar Panels?” He sees the mandate as an unnecessarily expensive way to increase alternative energy production.

However, California recently switched to a new form of net metering that takes into account time of use, which means customers will be paid at a lower rate for the solar energy they provide the grid during the hours of lowest electricity demand. Davis said this will help lessen the problem of cost-shifting.

5. Some think solar farms in the desert would be a better alternative.

Davis is among the energy economists who see grid-scale solar, or vast desert solar farms, as a better way to approach solar energy. He and fellow Haas professor Catherine Wolfram estimate it to be three times cheaper than rooftop solar, since it’s easier to install and maintain and can be placed somewhere with optimal sunlight. Wolfram also argues that it has the potential to make a bigger global impact.

“California produces a small share of world greenhouse gas emissions, so if we really want to help solve this global problem, we should be thinking about things we can do that will help India, China, Sub-Saharan Africa cause fewer greenhouse gas emissions,” Wolfram said. “So if we’re pushing something that is more expensive, like rooftop and not grid-scale, then to the extent we’re setting an example for the rest of the world, we’re setting the wrong example.”

Residential and commercial buildings combined are responsible for the least greenhouse gas emissions, compared to others like agriculture and, the worst offender, transportation.

6. Hawaii may offer a model for better rooftop solar.

In a response to the criticism from Davis and other energy economists, Ethan Elkind, Director of the Climate Program at the Center for Law, Energy & the Environment, wrote a blog post pointing to Hawaii as a model for how to make rooftop solar work. Utilities in Hawaii pay solar customers for surplus energy at a lower, wholesale rate, which has offset cost-shifting and in turn, encouraged people to buy batteries.

Elkind thinks California’s new net metering policy shows we’re moving toward this model, but he also argues that locally sourced energy provides a benefit to others on the grid: It saves the utility from having to ship in electricity from greater distances, which is not only expensive but also results in power loss along the way.

7. Private residences are not the biggest polluters in California, so the solar mandate won’t make that much of a difference by itself.

According to the Energy Information Administration, residential and commercial buildings combined are responsible for the least greenhouse gas emissions, compared to others like agriculture and, the worst offender, transportation. In fact, Elkind points out that the estimated emission reduction for all the CEC’s new standards combined—700,000 metric tons over three years—is tiny compared to the total amount of greenhouse gases emitted in California, about 440 million metric tons per year. “I wouldn’t call it a drop in the bucket, but it’s not by itself going to be our single most important strategy,” Elkind said. “But it is an important one.”